│By Caley Collins, Gale Ambassador at University College London (UCL)│

Unless you study literature, chances are poetry isn’t the first thing you would think to use as a primary source for an essay. However, poetry gives a fantastic first-hand insight into the language, values, and customs that people were concerned with during specific time periods, making it useful for a wide variety of degrees, including History and Politics. Gale’s Medieval and Renaissance collection, which is part of the British Literary Manuscripts Online archive, contains a vast collection of primary sources ranging from a 1066 Old English historical translation to a 1901 collection of medieval letters.

Using these sources, this post will explore the differences and similarities between poetry written over the course of several centuries. I will quote the sources using modern English spellings, but leave the titles as they were originally written out.

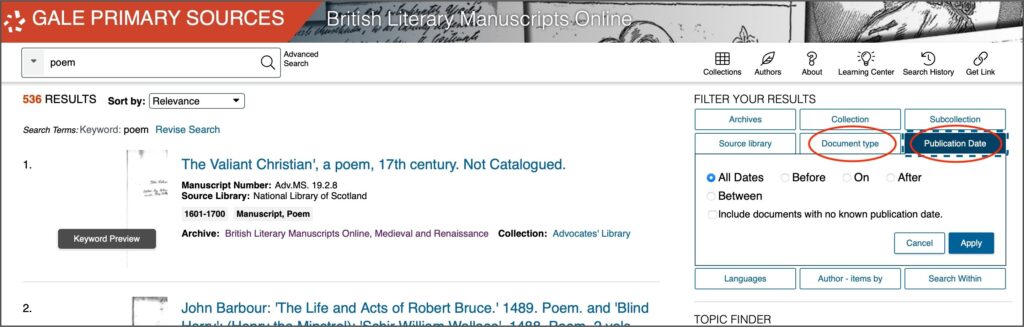

Searching for Poetry

When searching for poetry from a particular era, the easiest way is to use Gale’s results filter after conducting your original search. This allows you to select a date or a range of dates, meaning that the only poems displayed to you will be from the period of your choosing, saving both time and energy. You can also select ‘poem’ in the ‘document type’ filter, removing any results that merely discuss poetry. This is how each poem discussed in this post was chosen, with the relevant filters being circled in the example search below.

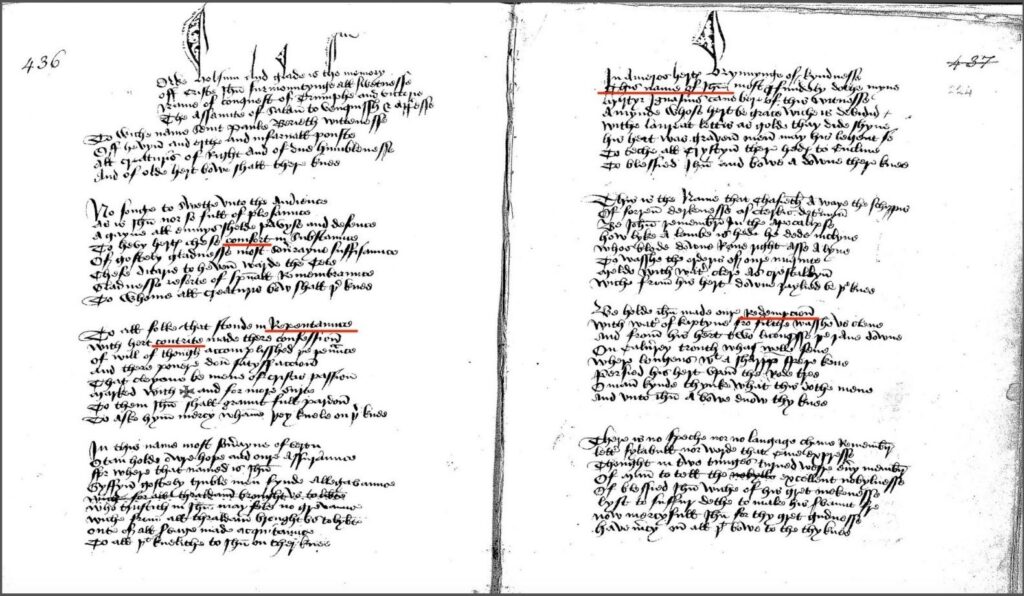

Pre-1200s Poetry

The first poem I selected is the final item (14) in Religious and moral treatises, poems, etc in Latin and English.

The first thing a reader notices about this source is the highly stylised cursive it is written in, distinguishing it from the writing styles of later centuries. Although it is difficult to read, modern readers can still pick out key words, including ‘comfort’, ‘repentance’, ‘contrite’, ‘high name of God’, and ‘redemption’. Although sometimes spelled differently, these words remain in our vocabulary today and indicate the poem’s primary themes of religious and moral instruction. Alongside the title, which confirms the poem’s focus on virtue, this gives us a good idea of what the poem is about, allowing us to compare it to later works.

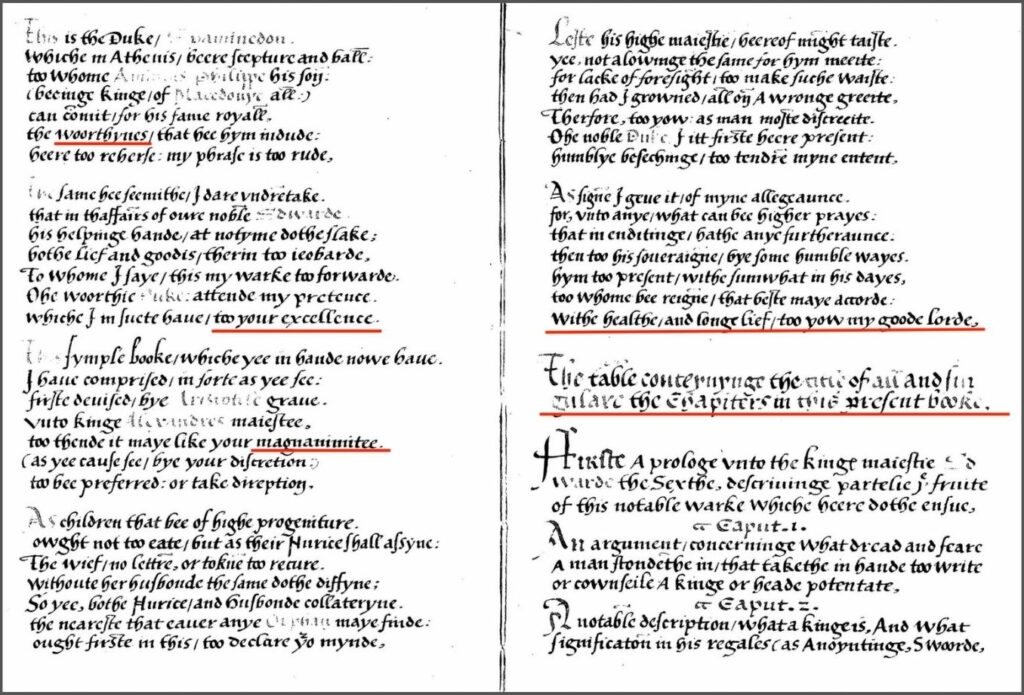

1200s Poetry

The second poem I have chosen is Sir William Forrest’s The Pleasaunt Poesye of princelie practise. Despite also being written in stylised cursive, this is much more legible for a modern reader, even if some of the words are unfamiliar. The poem’s purpose is to flatter the king, with themes of virtue being continued through the descriptions of his ‘worthiness’ and ‘magnanimity’. This indicates how the moralism of the previous century has continued, with the king being the most righteous person in the kingdom. The king is later also said to have been appointed by God, highlighting how religion remained a major influence on people’s lives, and thus their poetry.

This perception of the monarchy is very different to today’s view of sovereigns being ordinary people merely born into power, with this having led to a significant reduction in their political power. The outline of the rest of the poem, begun in the bottom left corner, highlights these differences, making it even more valuable as a primary source given that it contains a summary of its key ideas. This poem practically hands you the quotations needed for an essay!

1400s Poetry

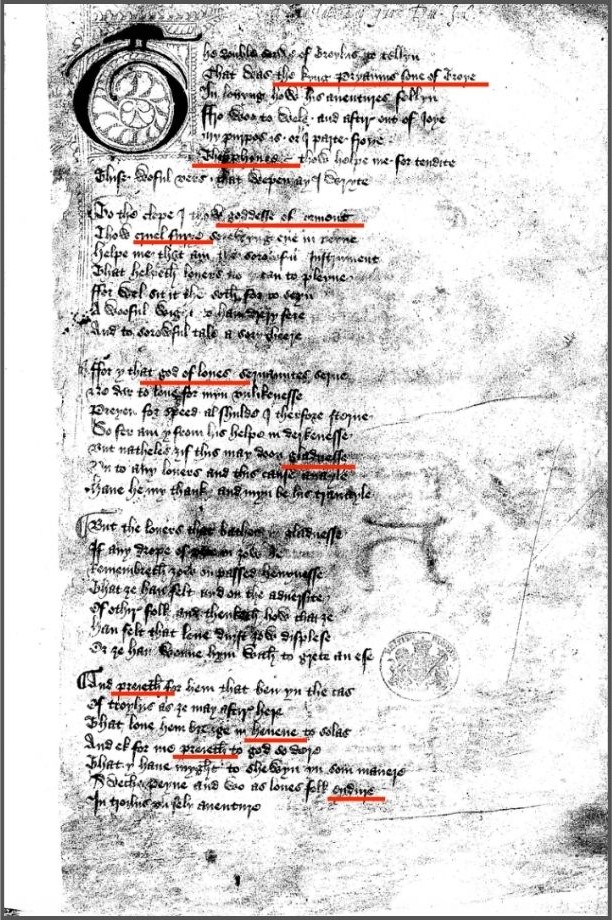

Skipping forward a few centuries, the next poem I discovered is beloved by many English students: Chaucer’s Poem of Troylus and Creaside.

Although the cursive can seem difficult to read, some key words are easily identifiable, and if you compare it to modern printed versions each word soon becomes clear. This is a brilliant primary source that displays the poem in its original format, better situating it in its period. Any good history student will be excited by the thought that this is the version that a few educated elites would have read! The ornate first letter certainly makes the text prettier to look at than the simple versions we see today.

This is also an interesting source for classics students, as it makes frequent references to mythological figures, such as ‘King Priam of Troy’, ‘cruel Fury’, ‘goddess of torment’, and ‘goddess of love’. This shows a different facet of medieval ideas on religion and morality, with attributes like the ability to ‘endure’ hardship and choosing to feel ‘gladness’ continuing to be referenced. However, this poem is primarily a tragic historical love story, with the focus being on the relationship between the lovers rather than their values. Contemporary audiences would have been entertained rather than educated by this text.

1600s Poetry

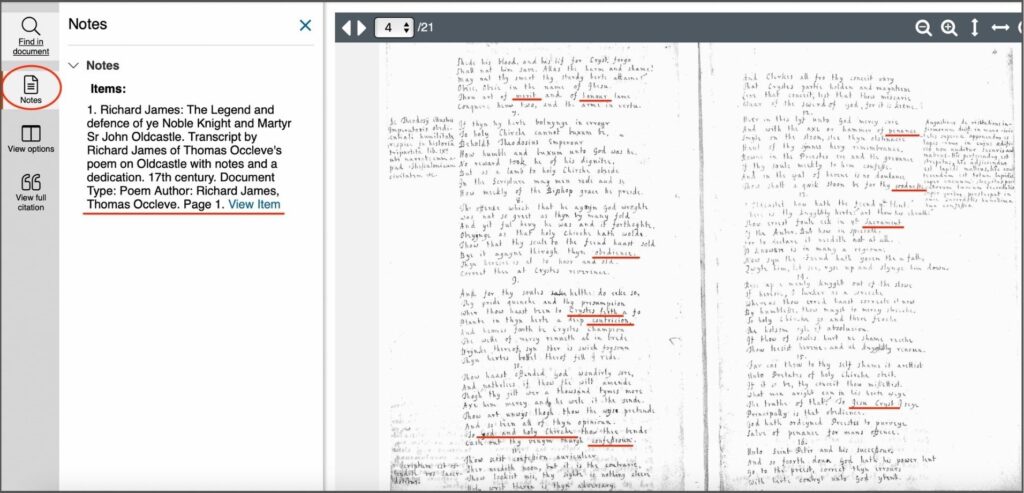

The final poem I sourced is Richard James’ The Legend and defence of ye Noble Knight and Martyr Sr John Oldcastle. Looking at the style the poem is written in, it is immediately clear that this is not an original manuscript, but instead a copy of one. This is confirmed in the notes on the poem’s origins, which can be found on the left-hand column of all Gale Primary Sources archives.

Interestingly, this poem returns to themes of religion and virtue that are similar to those of the poem dated to pre-1200, with concepts of ‘penance’, ‘contrition’, ’obedience’ and ‘God and holy Church’ being mentioned. It almost seems as though we are back where we started! However, this text is actually a narration of the life and death of a nobleman, with morality only forming part of this chivalric tale.

Development and Continuity

Did poetry change from pre-1200 to the 1600s? It’s clear that virtue and religion remained very prominent within texts from throughout the Medieval and Renaissance periods, so there was a level of continuity. However, whilst morality was sole focus of the first poem, in the others it became only part of political, romantic, and legendary narratives.

Even from this very limited selection of poems, we can learn that the topics covered by poetry hugely expanded, with their intended audiences also broadening. Despite the first two poems being written only for the educated elite and kings, the latter two were intended as forms of popular entertainment. After all, nothing beats a good story!

Therefore, using Gale’s Medieval and Renaissance collection, this blog has evidenced that poetry flourished and grew as a form of literature in the twelfth to seventeenth centuries. But why not have a look at the archives yourself, and discover even more about life in the Medieval and Renaissance eras? Whatever your degree, there’s always something new to learn!

If you enjoyed reading about poetry in the Medieval and Renaissance eras, check out these posts:

- An Overview of the Romantic Period using The Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive

- Examining the Emergence of Gothic Literature in the Early Nineteenth Century

- Exploring Receptions of Classical Literature with The Times Digital Archive and Gale Digital Scholar Lab

Cover image: “Photographs. Unidentified Woman, 1940.” The Papers of Vera “Jack” Holme, Gale, 1940. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/KEYGPP431362566/GDCS?u=ucl_ttda&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=82c4413d&pg=1