│By Liping Yang, Senior Manager, Academic Publishing│

The Flodden was a barque or three-masted sailing ship originally constructed in Britain and later sold to Australia and registered in Melbourne. On June 22, 1883, the ship departed from Fremantle, Western Australia, bound for Shanghai, carrying a cargo of 806 tons of sandalwood.

Unfortunately, on August 23, the ship ran aground near Nanhui, which is now a district of Shanghai. The captain, William Smith, made the decision for the crew to abandon the ship the following day and it was looted by some locals.

Negotiating the Losses

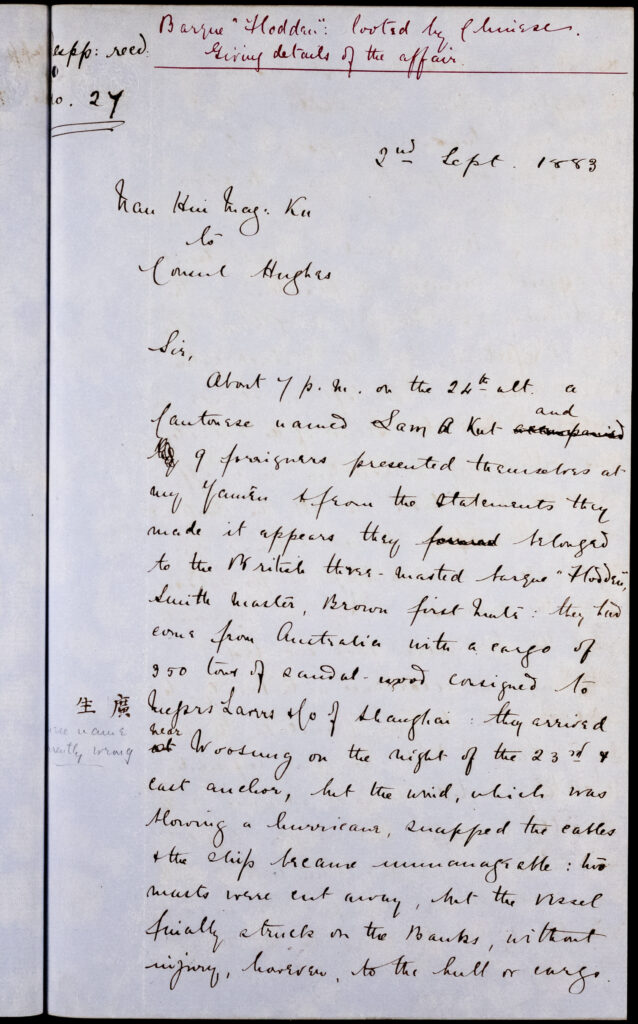

Following the looting incident, numerous stakeholders, such as the British consulate in Shanghai, the British Legation in Peking, the Foreign Office, the ship captain, the cargo consignee, and local Chinese officials including the Taotai and magistrate, engaged in a series of negotiations regarding the loss of cargo, liability, and the captain’s request for compensation from the Chinese government.

With the assistance of local Chinese officials, a significant portion of the stolen sandalwood was successfully returned. The dispatch from the magistrate of Nanhui, dated September 2, 1883, provides a comprehensive and detailed account of the events from the Chinese perspective.

At the same time, a marine court of inquiry was convened to investigate the incident and reached a verdict holding the captain, William Smith, responsible for the grounding and wrecking of the Flodden. The court determined he had “committed an error of judgement in making sail and slipping his bower…and also failed to take sufficient precautions for the protection of the cargo and hull.”

Additionally, the court concluded that the Chinese government had made sincere efforts to assist the crew and safeguard the ship. As a result, they were not obligated to pay any damages.

This case serves as an illustrative example of the bilateral trade between the two countries during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which primarily revolved around three commodities: sandalwood, tea, and coal.

Sandalwood Trade

The Chinese have a long-standing fascination with aromatic sandalwood which they utilized for various purposes, including the making of incense, and luxury items like inlaid boxes. Western Australia (WA) is home to one of the most notable species of sandalwood, trading of which began as early as the 1840s and became WA’s primary industry by the 1860s.

The industry involved harvesting, transporting to ports such as Fremantle, and exporting it to the port of Shanghai. British, Australian, and Chinese merchants were involved in the trade, either shipping the sandalwood directly to Shanghai or transshipping it via Singapore or Hong Kong.1 The case of the wrecked sailing ship Flodden, is a notable example.

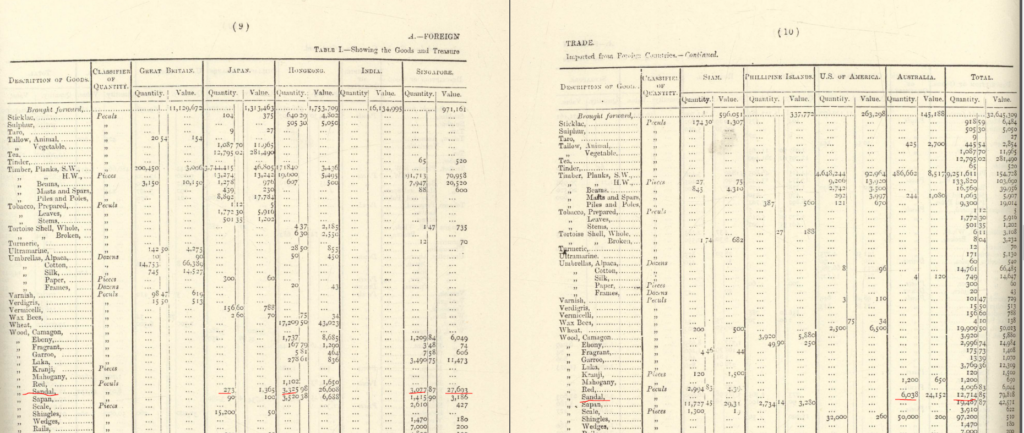

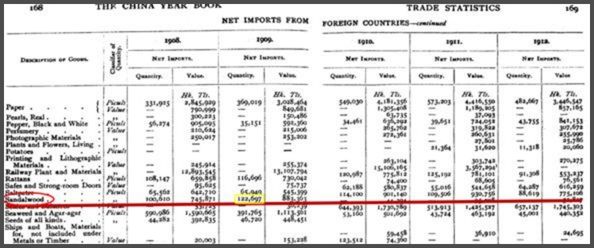

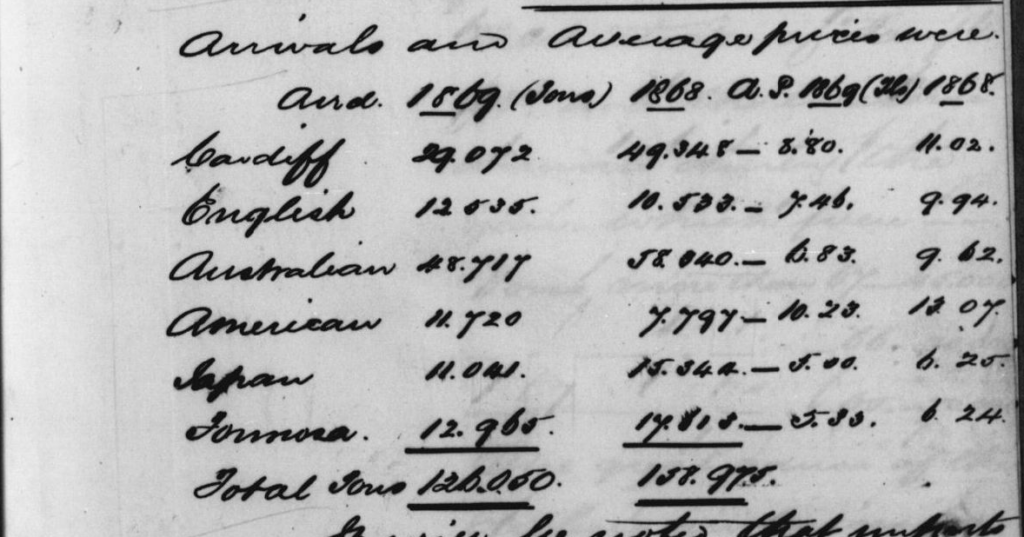

Based on the trade returns of Shanghai, the port’s total sandalwood imports in 1859 came to 26,623 piculs2 or 1.61 million kilograms through mostly British-owned vessels. Sandalwood imports from Australia accounted for about 98% of China’s total imports of the wood in that year. In 1864, the port’s total sandalwood imports dropped—largely due to the impact of the Taiping Rebellion—to 12,714 piculs or 768,930 kilograms.

In 1868, China’s total sandalwood imports jumped to 40,789.67 piculs or 2.47 million kilograms. This number continued to increase in the early 20th century, reaching a record 122,697 piculs (7.42 million kilograms) in 1909. Thereafter, the imports declined gradually.

Tea Trade

As a part of the British Empire, Australia inherited the British tea culture. Most of the tea consumed in Australia was imported directly from the southeastern Chinese port of Fuzhou (Foochow). It was primarily transported by sailing vessels to Melbourne and Sydney, from where it was distributed.

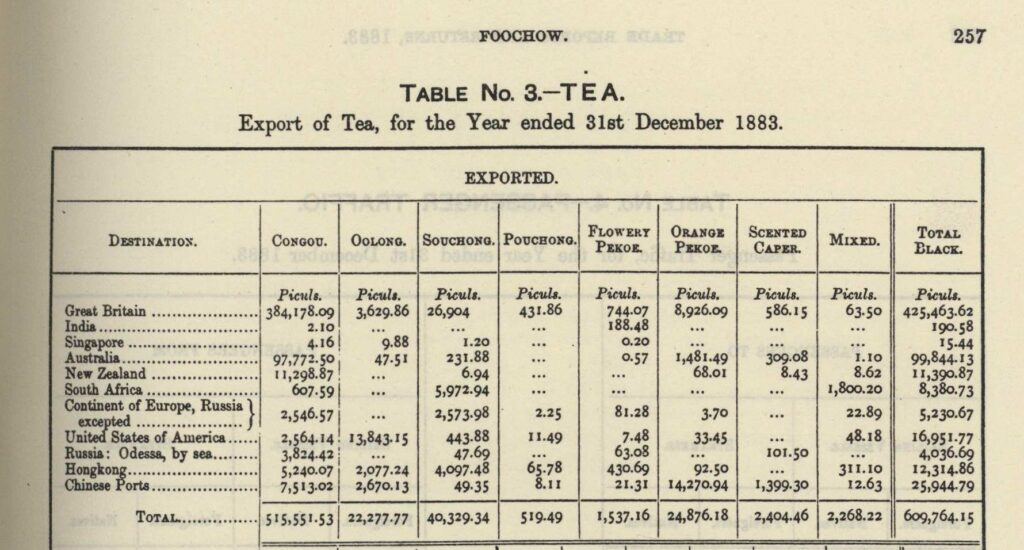

From the 1850s to the early 1900s, Australia was one of the top four global importers of tea. It even ranked above all other foreign countries in terms of per capita annual consumption of tea, ranging between 6.83 and 8.05 pounds during 1888-1910.3 In 1883, Australia surpassed the US in tea imports, bringing in a total of 99,844 piculs or 6.4 million kilograms becoming the second largest importer of Chinese tea.

Thereafter, Australian tea imports from China experienced a significant decline, reaching 956,666 pounds or 433,936 kilograms in 1907. One of the primary factors contributing to this decline was the competition posed by cheaper Indian tea. From the 1880s onwards, Indian tea had gradually gained market share in the West, eroding the dominance of Chinese tea.4

Coal Trade

Black coal was first discovered in New South Wales (NSW) in the 1790s and then in Queensland and Victora in the 1820s. By the early 1860s, NSW started exporting around the world, with China becoming one of its principal overseas destinations.

Like sandalwood, Australian coal was exported to China mainly through the port of Shanghai. Coal contributed about half of all Australian exports to Shanghai in the 1860s while sandalwood covered roughly the remainder. It was mainly used “for smelting and making into cakes for stove fuel” as well as powering the engines of British naval and commercial steamships.5

Britain was Australia’s main competitor for coal export to China. In 1868, Chinese imports of Australian coal at Shanghai totaled 58,340 tons, quite close in quantity to the total imports of British coal (59,881 tons). In 1869, Australia overtook Britain to become the largest coal exporter to China against the background of reduced overall foreign coal imports during that year.

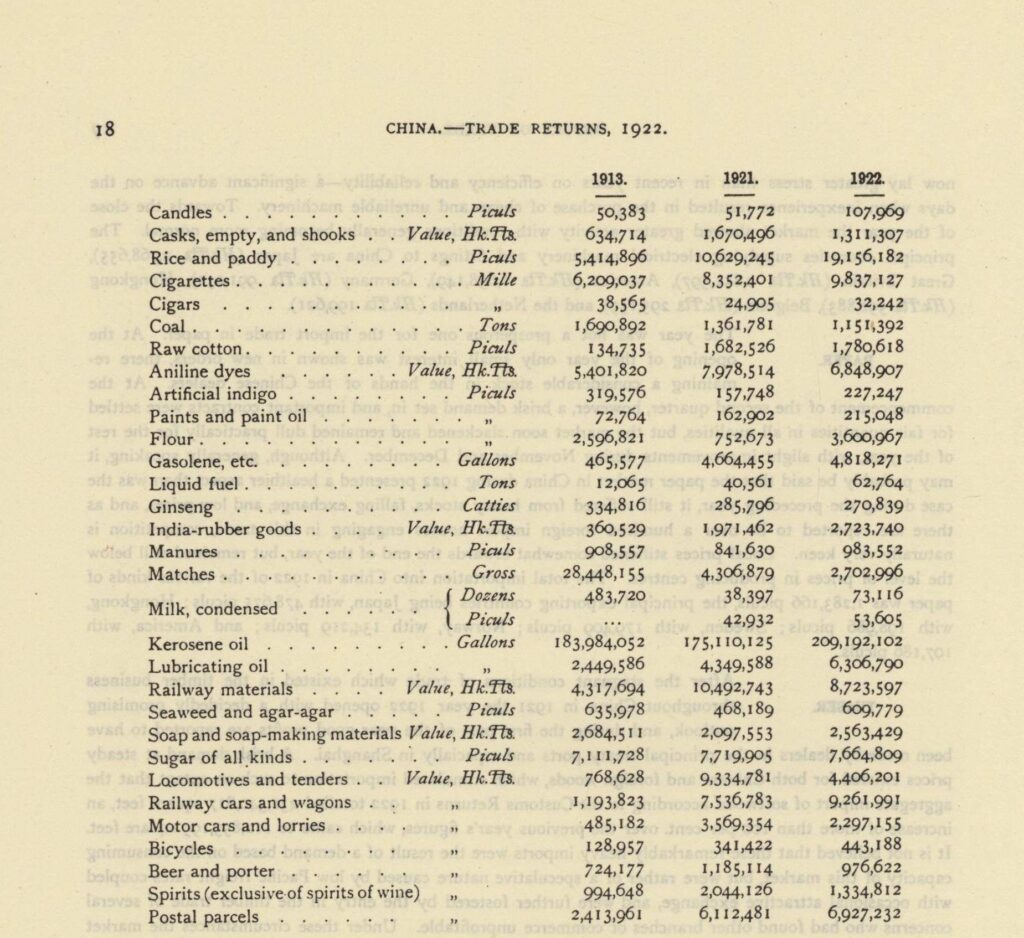

However, it was not long before Britain caught up again. China’s coal imports climbed in 1913 to 1,690,892 tons before declining gradually to 1,151,392 tons in 1922. Among the main factors behind this decline was the rise of the Chinese coal mining industry and competition from Japan and Formosa (Taiwan).

China’s coal imports from Australia experienced a further decline in the 1940s, with figures dropping to 1,111 and 1,711 tons in 1946 and 1947, respectively. This import volume dramatically plummeted to a mere 51 tons in 1948. Such significant decrease can be attributed to the severe impact of the ongoing Chinese civil war (1946-1949).6

Intertwining of Trade and Political Relations

The China Critic, a Shanghai-based English periodical, published an editorial titled “China and Australia” in its August 27, 1931 issue in response to an Australian businessman’s remarks that “Australia can undersell other countries in trade with China and the two countries can do a good deal of business together.” The author stressed that business and politics could not be separated from each other in China. The Australians were advised to “scatter all your ‘white man’s pride’ to the wind and remove your immigration discrimination against the Asiatics and cultivate your goodwill for the Chinese people before your come to do business.”7

This article highlighted a key recurring issue that has influenced China-Australian relations for over a century: Chinese immigration and Australia’s varied responses to it. Restriction and discrimination against Chinese immigrants have sparked political tussles between the two governments and impacted bilateral trade ties.

Opposition to Chinese immigration by European immigrants in Australia started in the 1860s and reached a peak in 1888 when all colonies passed a slew of restrictive laws and policies aimed for complete exclusion of Chinese. All these had directly led to the Afghan affair.

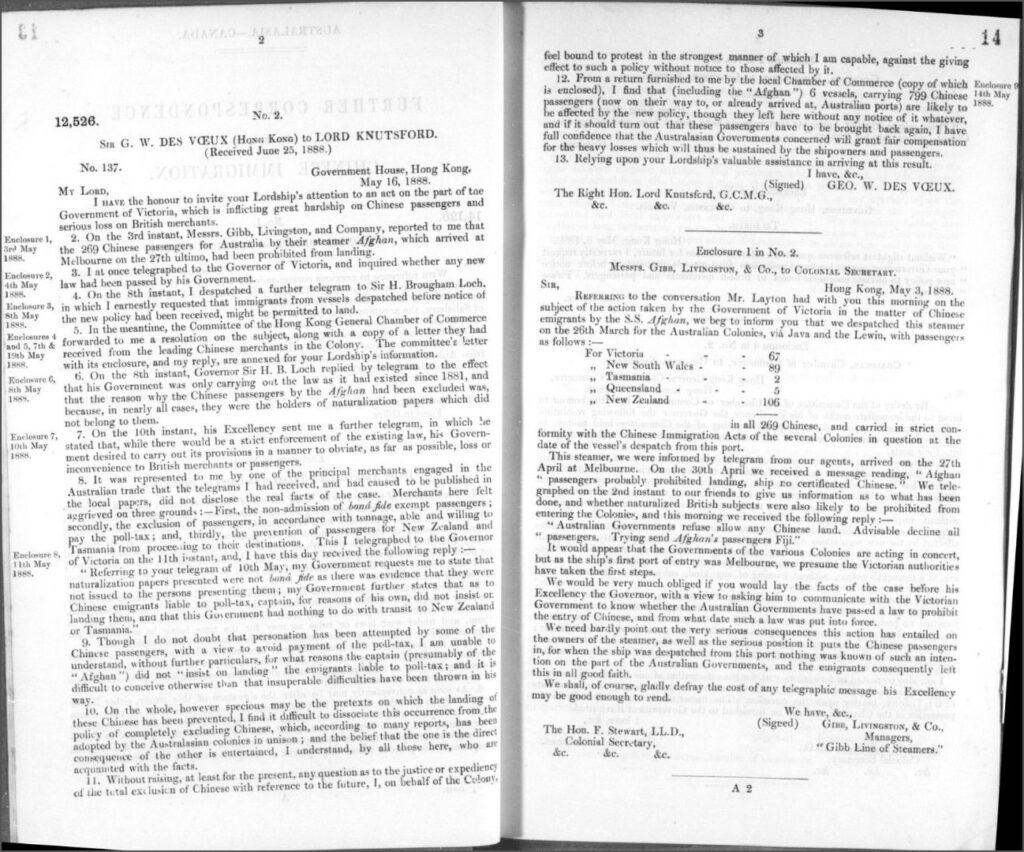

The SS Afghan was an immigrant steamer owned by Hong Kong-based Messrs. Gibb Livingston and Company. Carrying 269 Chinese passengers, the ship arrived at Melbourne on April 27, 1888, but was stopped from disembarking on the grounds of fraudulent naturalization papers presented and the newly introduced policy of limiting the number of passengers by the tonnage. The ship was surrounded by police, passengers were subjected to strict medical quarantine measures and banned from landing.

The crisis triggered heated discussions among colonial governments of Hong Kong and Victoria, the Colonial and Foreign Offices, Hong Kong Chamber of Commerce, and the shipping company. The government of Victoria defended its restrictive measures by citing the local anti-Chinese sentiments whereas the Colonial and Foreign Offices wanted to sustain free movement of people and goods between Australia and Hong Kong/China in the context of maintaining a policy of greater engagement with Asia.

The affair marked a turning point in the history of the Chinese in Australia, paving the way for the notorious White Australia policy and the exclusion of Asian immigrants for the next 80 years.

The Legacy of Trading Relations

The intertwining of bilateral trade and political relations between China and Australia has endured beyond the era of the White Australia Policy and extended into the twenty first century. The diplomatic tensions between the two countries during the administration of Scott J. Morrison (2018–2022) led to a trade war characterized by China imposing sanctions on Australian imports. This strained relationship did not see a positive turn until Anthony Albanese took office in June 2022.

If you enjoyed reading about Chinese and Australian relations, check out these posts:

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- The Silk Road Yesterday and Today in Gale Digital Resources

- Asia, as Recorded in British Colonial Office Files

Blog post cover image citation: “The Barque Flodden of Blyth Captain D J Manners off Cape Le Heve Bound to Havre May 10th 1871” (watercolour) https://www.mutualart.com/Artwork/The-Barque-Flodden-of-Blyth-Captain-D-J-/35309C402FC0F6D5

- Nicholas Dennis Guoth, “Beyond a cup of tea: Trade relationships between colonial Australia and China, 1860-1880,” Australian National University Open Research Repository, 2017, http://hdl.handle.net/1885/144322

- A traditional Asian unit of weight, mainly used in China, Japan, and Southeast Asia. 1 picul is equal to approximately 60 kilograms or 133 pounds.

- “Table VI: Per Capita Consumption of Team, 1888-1908″ in Chapter XI Trade Statistics. The China Year Book, 1913, pp. 120+. China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MLMQVT284526053/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=914c9df5.

- China. The Maritime Customs. I.—Statistical Series: No. 6. Decennial Reports on the Trade, Industries, Etc., of the Ports Open to Foreign Commerce, and on Conditions and Development of the Treaty Port Provinces; Preceded by “A History of the External Trade of China, 1834-81,” Together with a “Synopsis of the External Trade of China, 1882-1931.”. Vol. 3, Order of the Inspector General of Customs; the Statistical Department of the Inspectorate General of Customs, 1933. Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/ZJOWWP155918167/GDSC?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDSC&xid=d35f299c&pg=84, 136-137

- CHINA: Report. Trade of Shanghai. Note: Bound: China 68. 1910. MS FO 881 Foreign Office: Confidential Print. FO 881/1858. China and the Modern World: Records of Shanghai and the International Settlement, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/NCEWFH384859246/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&pg=9.

- Chinese Maritime Customs. I.—Statistical Series: No. 1. The Trade of China, 1948. Vol. 2. Archives Unbound: Chinese Maritime Customs Service Publications, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/ZJKDNP593075273/GDSC?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDSC&xid=441db581&pg=396.

- “China and Australia.” The China Critic, vol. 4, no. 35, 27 Aug. 1931, pp. 819+. China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals. . https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/GLZZNM004212592/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER .