│By Olivia McDermott, Gale Ambassador at the University of Liverpool│

For a subject such as drama, primary sources are continuously overlooked. Much academic study preceding degree level tends to focus on the practical realm of theatre. Though it is an important aspect, this sometimes leads to contextual ideas being ignored.

The Role of Primary Sources

As this perspective began shifting during my first year at university as an English Literature student, it became clear that I could not solely rely on watching recorded performances to construct my essays. I started delving into secondary material which contained endless theories exploring new ways of engaging with performance. I came across all sorts of interesting concepts, ranging from critical race to feminist and Marxist.

I was now familiar with practical terms and becoming more confident with theoretical approaches, yet for me, something was still missing. There was another component that I knew would be capable of providing theatre studies with a third dimension and that was when I discovered primary sources.

The archives in Gale Primary Sources informed me about how plays were initially received by audiences, how censorship has changed over time, what theatres used to look like and perhaps most shockingly, their power to fight social issues. It was reading about what real people had to say and how they felt in relation to topics as broad as race, gender and sexuality, that propelled my understanding of the significance of theatre within everyday life.

From life in prison to touring with Samuel Beckett

Whether you have studied theatre or not, most people will have stumbled across many prominent playwrights. From William Shakespeare to Henrik Ibsen, Sarah Kane and Bertolt Brecht, these names are synonymous with having remarkable careers in theatre.

However, I have been studying drama for seven years and had never heard the name Rick Cluchey until undertaking some research in relation to Samuel Beckett’s Theatre of the Absurd. In an article from the Archives of Sexuality and Gender, I discovered that Cluchey was a man sentenced to life in prison in 1955. During his imprisonment, he watched a performance of Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, which led him to form his own theatre company upon his release from prison, The San Quentin Drama Workshop.

In the article, Cluchey also speaks about the transformative and creative power that performing had over him. It saved him from believing that he did not possess any redeemable qualities. Through Gale Primary Sources, I was able to appreciate the importance of theatre in the lives of individual people and its restorative power. Though my essay research began as an attempt to find out more about Theatre of the Absurd, I left more interested in theatre’s ability to restore and rehabilitate a truly troubled man. What could be more absurd than that?

Actors or Vagabonds?

Though theatre and performance can be viewed as creative and exciting, I simultaneously wanted to explore the more negative perceptions of drama that do exist. At this point, I was approaching the beginning of my second year at university. One of the modules that I took was titled ‘Drama 1580-1640‘ and so I began researching different attitudes towards theatre during this period.

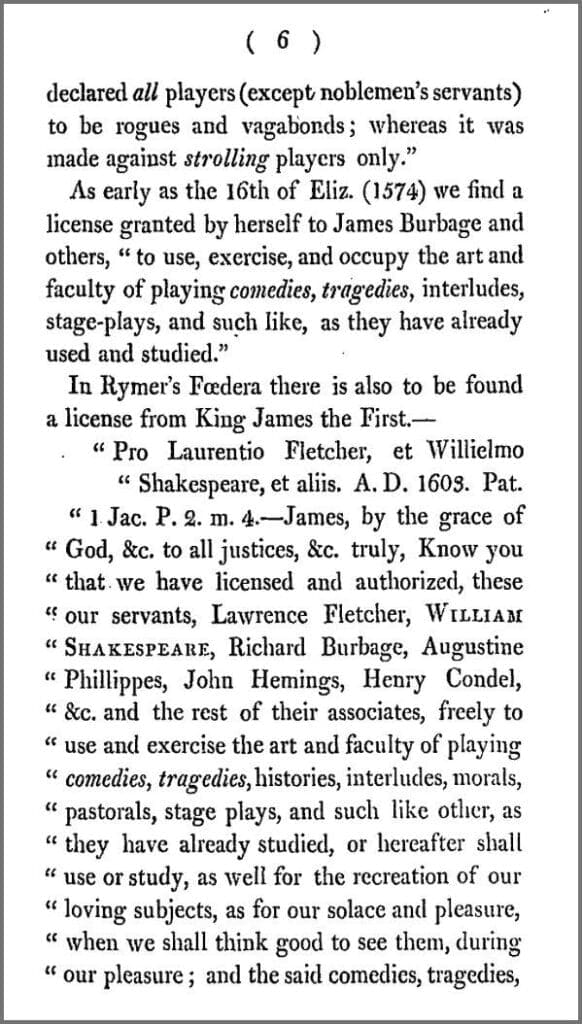

In The Making of the Modern World, I stumbled across a letter (below) that was sent to parliament and published in 1824. Though falling out of the date range within my module, there were several sections that explored how theatre was managed during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign (1558-1603).

Even though this letter criticises the government for labelling actors as “rogues and vagabonds”, the author highlights the alternatively liberal attitude towards theatre from over 250 years before. In a licence granted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1574, she allows permission “to use, exercise and occupy the art and faculty of playing comedies, tragedies, interludes, stage-plays and such like”. Thus, it became clear that this contrasting reception of plays and acting has been commonplace since theatre emerged.

Exploring contextual ideas and individual responses of activism, are critical parts of learning about theatre. This letter gives direct insight into the challenges that actors faced at the end of the Tudor period, reflecting the struggles within the arts today.

Theatre in the Fight Against Fascism

Fast forward to the twentieth century and theatre’s role within the public domain becomes more significant. Whereas in previous centuries acting was placed alongside other art forms that encouraged escapism, during the rise of political extremism, theatre became a way of protesting.

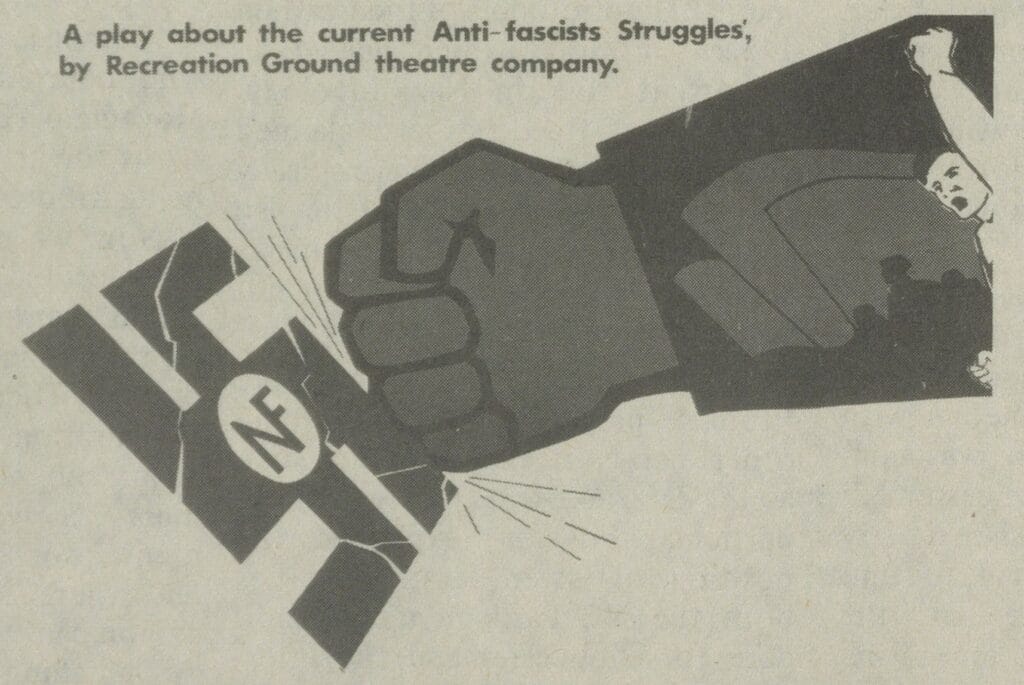

This Gale Primary Sources document from Political Extremism and Radicalism gives a direct account of the impact that the theatre group Recreation Ground had during the 1930s. Not only dedicated to giving marginalised voices a platform, the theatre company also performed in an unconventional way. Recreation Ground demanded that their audiences give them constructive feedback after watching their plays, so key messages could be delivered more effectively.

From comparing actors to vagabonds, and drama saving a man sentenced to life in prison, here, we see theatre as something with the potential to encourage conversations surrounding ethics, diversity and inclusion.

To attend or not to attend: Is there a concession?

Theatre is an incredible art form that simultaneously possesses the power to both liberate and educate. Gale Primary Sources have been a constant point of reliable support while I continue to undertake research during my degree. The most exciting research takes place when stumbling upon ideas that you had no idea even existed; something that often happens as I browse through the endless resources from Gale. As a supporter of theatre and the power of performance, I am passionate about making this type of art available to everyone.

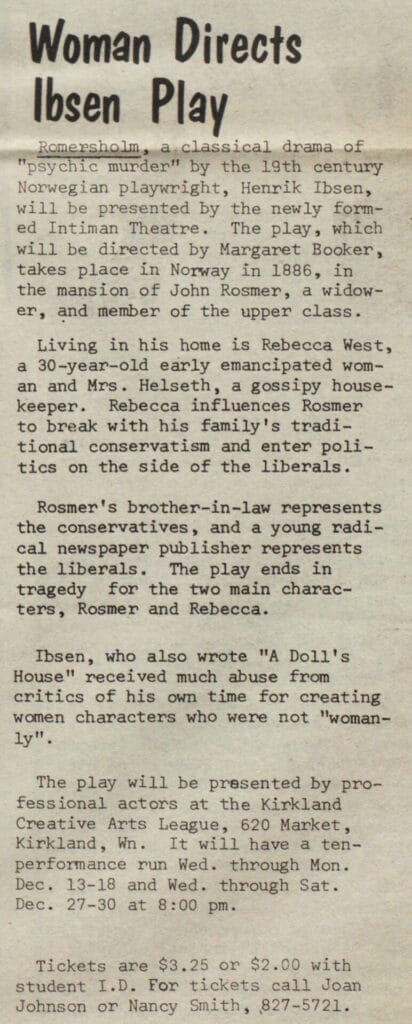

The article above is a screenshot from an American Journal called Pandora that highlights the concessions made available to students wishing to attend a version of A Doll’s House, directed by Margret Booker. Next time a play is being performed in your local area, at your university, do not miss it! And answer any questions it asks you by using Gale’s incredible online learning platform.

If you enjoyed reading about how Primary Sources can be used in relation to Theatre Studies, check out these posts:

- Keeping Your Love of Literature Alive While Studying at University

- A Media and Journalism Student is Thrilled to Discover Gale!

- How Gale Literature Provided Vital Support for My Dissertation

Blog post cover image citation: Solomon, Les. “Waiting for Samuel Beckett.” Campaign, no. 103, July 1984, p. 39. Archives of Sexuality and Gender link.gale.com/apps/doc/KBDRZB148941142/AHSI?u=livuni&sid=bookmark-AHSI&xid=67a1ab21