│By Jessica Crawley, Gale Ambassador at Lancaster University│

One of the most interesting and – to some – most perplexing aspects of philosophical writings is that newer does not equal better. For example, some of the greatest advancements in metaphysics were made by Aristotle, who was writing in Ancient Greece well over two-thousand years ago. Not only this, but our gendered and Western-mandated criteria of what ‘deserves’ the title of ‘philosophical writing’ is (finally) beginning to evolve.

Students can often mistake ‘primary sources’ to be little more than an academic buzzword, but in the changing world of philosophy, primary sources are now more important than ever.

When writing this blog on how Gale Primary Sources could be utilised in philosophical studies, I could have discussed the vast array of transcribed lectures about Plato, the countless critical essays on Kant, or the many available musings of Nietzsche. Instead, I decided to focus my attention on the area of Philosophy that interests me the most: re-reading, deconstructing, and redefining primary sources that aren’t typically deemed to be philosophical (at least by Western and largely gendered standards, that is).

Primary Sources and Their Importance in Philosophy

Put simply, a primary source is the original object or document that contains first-hand uninterpreted information about a particular topic. Primary sources are super important in academia for a variety of reasons, but – for the purpose of this blog – primary sources allow us to revisit the thoughts and feelings of different people and cultures.

This means that we can decipher their philosophical outlook based on what was previously deemed to be un-philosophical works simply because the method of transmission may differ from what we are used to. It is important to note that the reasons behind these differing methods are usually due to cultural differences or gendered discrimination, so in most cases, redefining what ‘philosophy’ means is essential to hearing from different philosophical voices throughout our histories.

For the remainder of this blog, I will be illustrating my philosophical analysis of various primary sources found in Gale’s archives. For a more comprehensive guide on how you can find sources such as those in my analyses, check out this article: ‘Finding Primary Sources Using Gale’s Alternative Search Tools’.

Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia

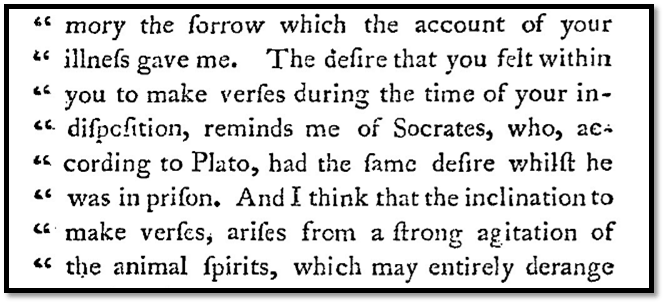

Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia was known to be something of a student to the widely proclaimed Father of Modern Philosophy, René Descartes, who is most famous for his theories surrounding mind-body dualism (which is basically the idea that the mind/soul is a separate entity to the body). The pair would regularly exchange letters about Descartes’ theories and their daily lives, and many of these letters are revered by the philosophical community to contain unique perspectives from Descartes himself.

While Descartes’ letters to Princess Elizabeth are held in great esteem, the letters from Princess Elizabeth are seen in nowhere near as high regard. Transcripts and quotations from Descartes’ letters can be found in many books and academic papers, but Princess Elizabeth’s letters prove much more difficult to access. Therefore, unfortunately, Princess Elizabeth’s doctrine must mainly be understood by deconstructing the words of Descartes.

The extract above was taken from a letter Descartes wrote to Princess Elizabeth upon the execution of her uncle, Charles I. Descartes likens Princess Elizabeth’s desire to make verses to that of Socrates, an extremely famous ancient philosopher. Descartes later goes on to suggest that this is indicative of “an understanding more strong and more exalted than the common run of understandings.”

With this in mind, we begin to decipher Princess Elizabeth’s philosophy surrounding life and loss, and how both can be admirably approached.

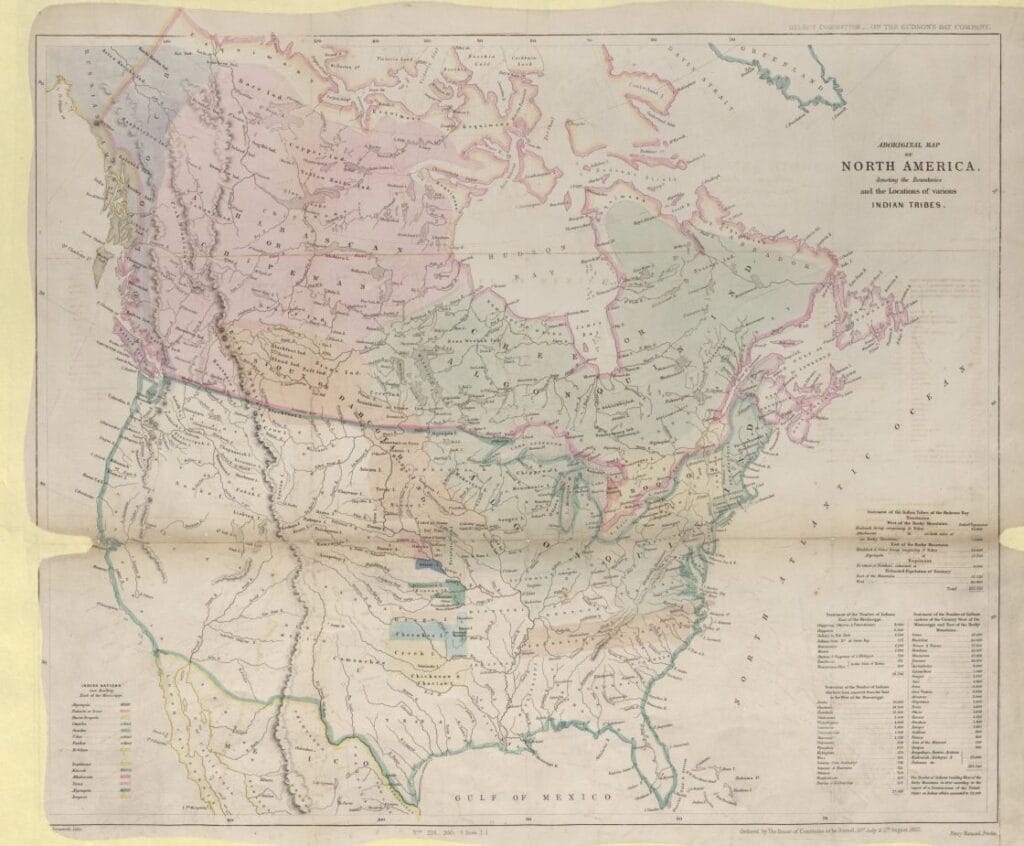

The Iroquois Creation Story

The term ‘Iroquois’ represents six Native American tribes – the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora. The Iroquois had an extremely vibrant culture which included mythology, theology, and traditions.

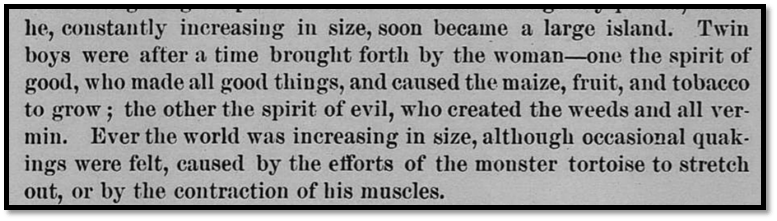

The Iroquois Creation Story was passed from one generation to the next via oral transmission and depicts the Iroquoian origin of humanity. There are many transcribed versions of the Creation Story out there but, generally, the tale follows a woman who falls into the underworld and rests on the back of a turtle. The turtle grows to become an island, where the woman births twins; one the spirit of good, and the other of evil. Each twin created different aspects of the world as we know it – for example, the good created the sun, the evil created the moon.

While the Creation Story is technically a theology, it was widely regarded by the Iroquois as a true history that they would have carried throughout their daily lives. Unlike many Western outlooks, the Iroquois Creation Story depicts the necessity of both good and bad, and illustrates them as equally crucial for a thriving and balanced world. Similar philosophical outlooks can be seen all over the globe (such as in ancient Indian and Chinese Philosophy) but have only become popularised in the West over recent years.

The Changing World of Philosophy

The world of Philosophy is changing, and the way we research it should too. It’s time to look at primary sources in a different light and use them to piece together the voices that have been silenced for so long. Gale Primary Sources allows you to do just that – and quickly too, with documents available that express more than just westernised male thoughts.

If you enjoyed reading about using primary sources to break down the barriers of what philosophy is, check out these posts:

- Exploring the Rise of Black Consciousness in South Africa using Gale Primary Sources

- Finding Black Female Authors in the Women’s Studies Archive

- Researching and Teaching Women Writers Using Eighteenth Century Collections Online

Blog post cover image citation: Porter, Roy. “A Grand Tour of the head.” Books. Sunday Times, 30 Aug. 1992, p. 4[S4]. The Sunday Times Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/FP1803115382/GDCS?u=unilanc&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=01f34470.