|By Liping Yang, Senior Manager, Academic Publishing, Gale|

November 2023 marks the 180th anniversary of Shanghai being opened to foreign trade in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty of Nanjing and the Treaty of the Bogue, which were signed after the First Opium War between China and Britain.

Coincidentally, in the same month, Gale Primary Sources rolled out a thematic digital archive that features the history of Shanghai. Titled China and the Modern World: Records of Shanghai and the International Settlement, 1836–1955, this new archive provides an extraordinary primary source collection vital to understanding and researching the social, political, and economic history of the Anglo-America-dominated yet highly globalised International Settlement in Shanghai, as well as the history of modern China.

China and the Modern World: Records of Shanghai and the International Settlement, 1836-1955

This Shanghai-focused archive consists of approximately 370,000 pages of rare British government records and documents now held at the prestigious The National Archives in Kew, UK. The bulk of the content is formed by nine series of British Foreign Office files directly related to the history of Shanghai and the International Settlement. At the same time, a small number of files pertaining to this Chinese city have also been selected from the records of the British Ministry of Labour, Treasury, and War Office.

All these government records and documents are digitised for the first time, providing a wonderful collection for (re)discovering the history of Shanghai and the International Settlement therein from various perspectives, such as political, commercial, military, cultural, and legal. It will appeal to scholars around the world researching Chinese treaty ports, informal empires (semi-colonialism), transnational colonialism, globalisation, urban studies, and the history of modern China.

The archive covers an array of research topics and historical events that played out in Shanghai and shaped China’s relationships with Britain and other Western powers.

Extraterritoriality and the Mixed Court Riot

One unique feature of the Shanghai International Settlement is that there was not a unified legal system within its boundaries. On the one hand, the American and British governments established their own Shanghai-based consular courts for trying and prosecuting their own citizens and subjects who had committed any civil or criminal offenses per their respective laws. This is the so-called legal extraterritoriality warranted by the various unequal treaties imposed by the Western powers on China since the First Opium War (1839–1842). Such extraterritoriality is also reflected in the “Mixed Court,” a hybrid legal system implemented in the Shanghai International Settlement between 1864 and 1927.

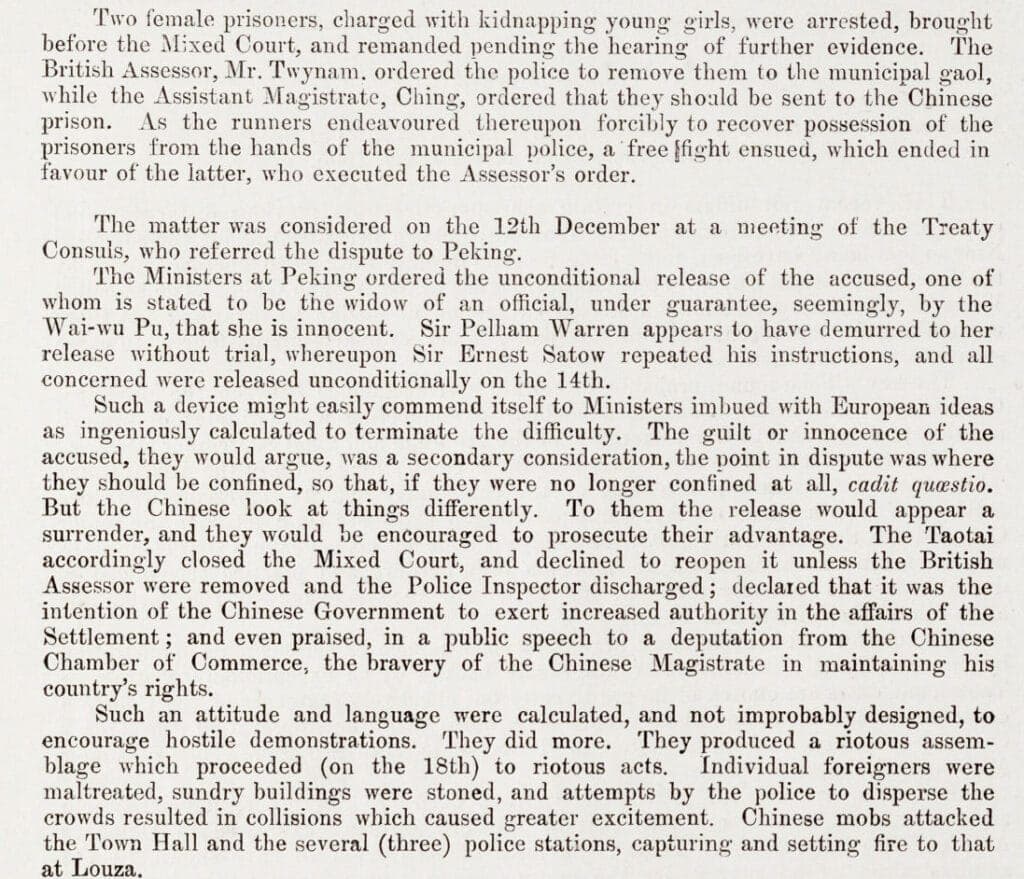

The Mixed Court was created to try cases involving Chinese citizens and citizens of non-treaty powers residing in the Settlement, or between Chinese citizens according to Chinese law. It was “mixed” because when a case involved a Chinese and a foreigner, a Chinese magistrate and foreign assessor needed to sit together in the hearing process. This unique legal system gave rise to frequent disputes and even conflicts.

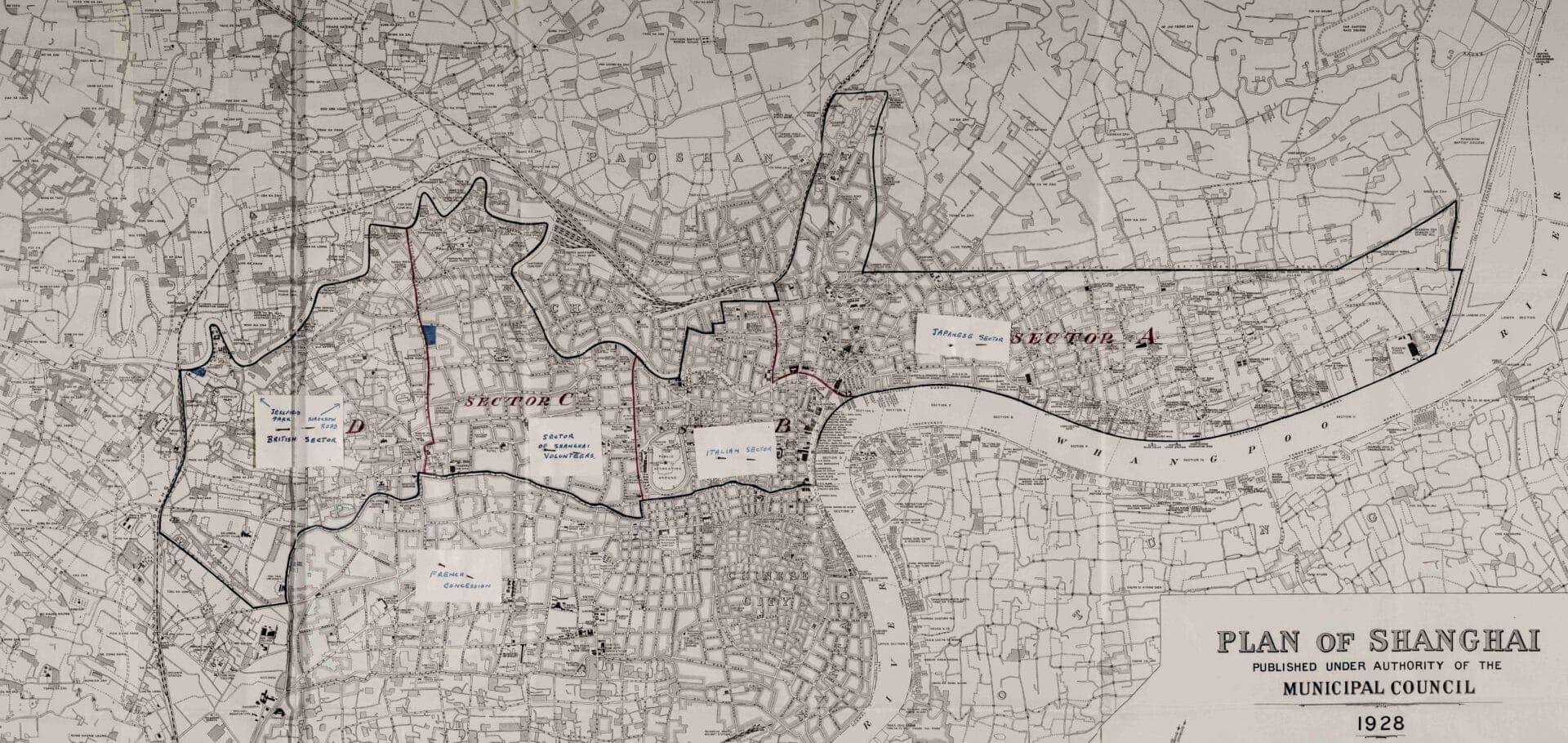

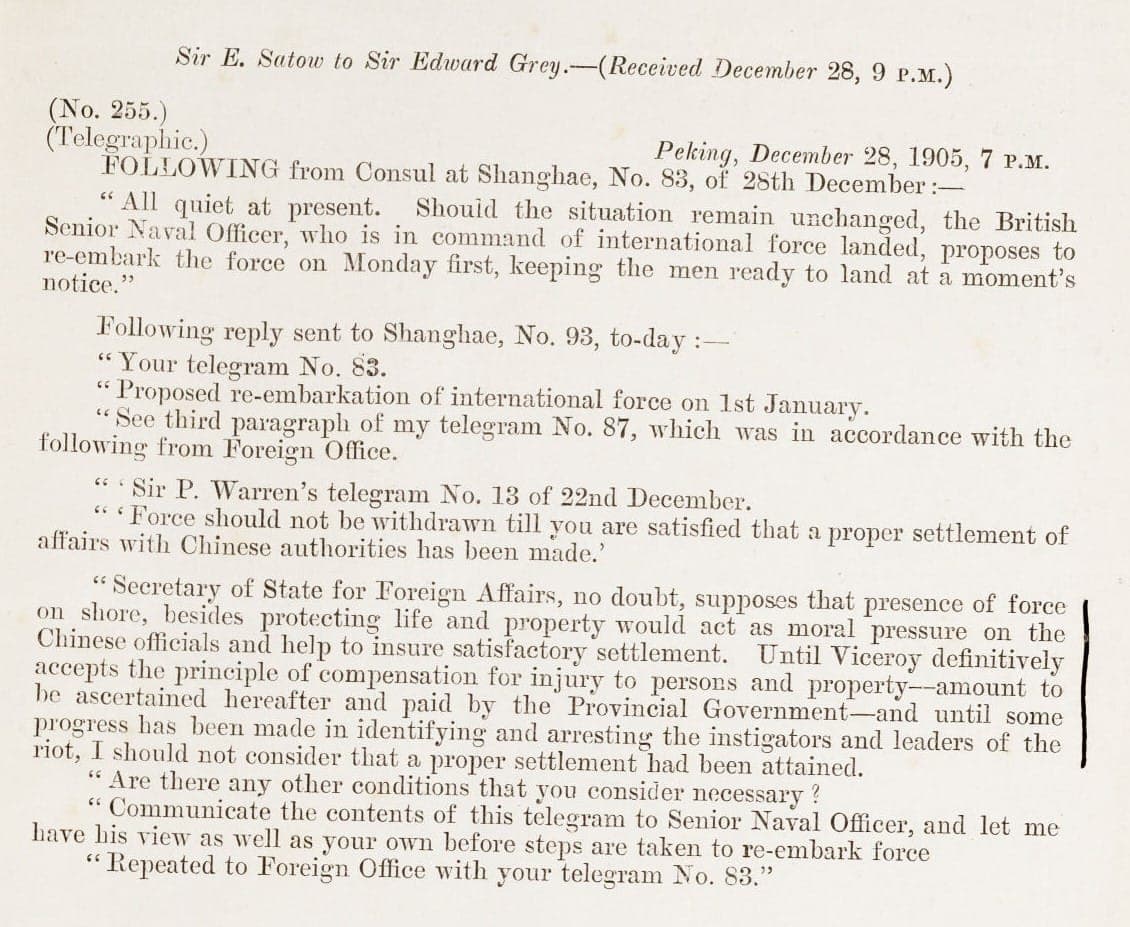

A case in point is the December 1905 Shanghai riot. It started with a fracas on December 8th, 1905, during a Mixed Court trial of two Chinese women accused of kidnapping young girls. The Chinese magistrate and British assessor had an argument over where the accused should be confined: the Chinese prison or municipal gaol? This dispute escalated on December 18th into a large-scale boycott and protest by Chinese merchants and workers.

In a dispatch of December 28th, 1905 to Sir Edward Grey, Sir Ernest Satow, then British minister to China, touched on the riot’s impact on the Settlement, the British navy’s readiness to “re-embark” and “land” at Shanghai, and the question of how to extract compensation and punishment from the Chinese government.

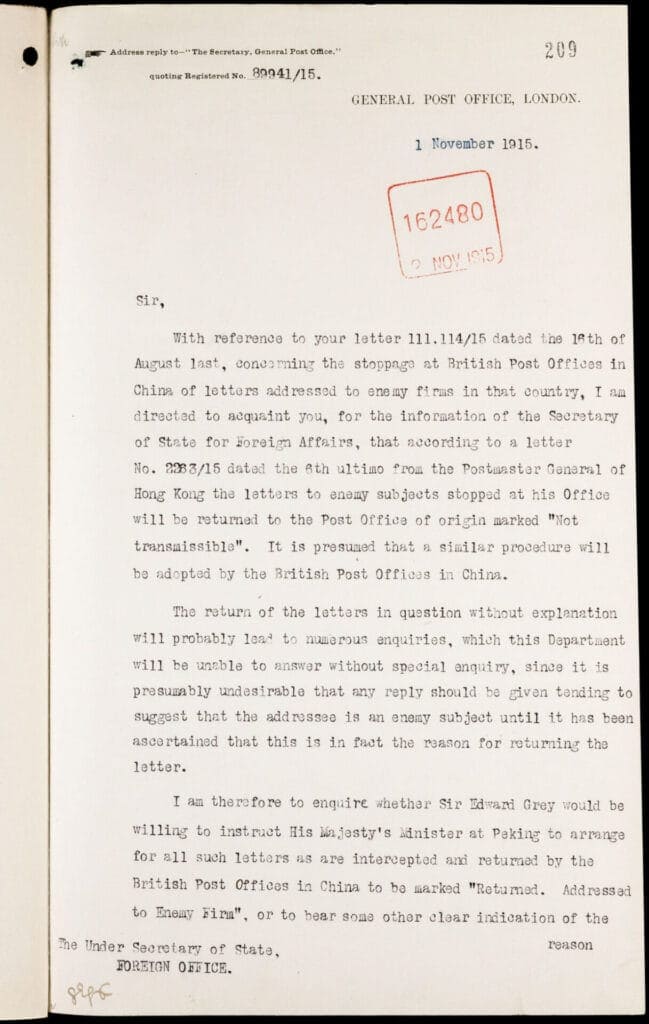

The First World War

While World War I is generally considered a European War, it also affected China in various ways. The Beiyang government in Beijing declared war on Germany and dispatched the Chinese labor corps to Europe to assist the British and French armies. Within China, especially within the British-controlled treaty ports and concessions, the British government tried various means to restrict the activities of the enemy (German) firms and subjects. These include actions taken by the British post offices to monitor and censor mails to and from German firms within British concessions.

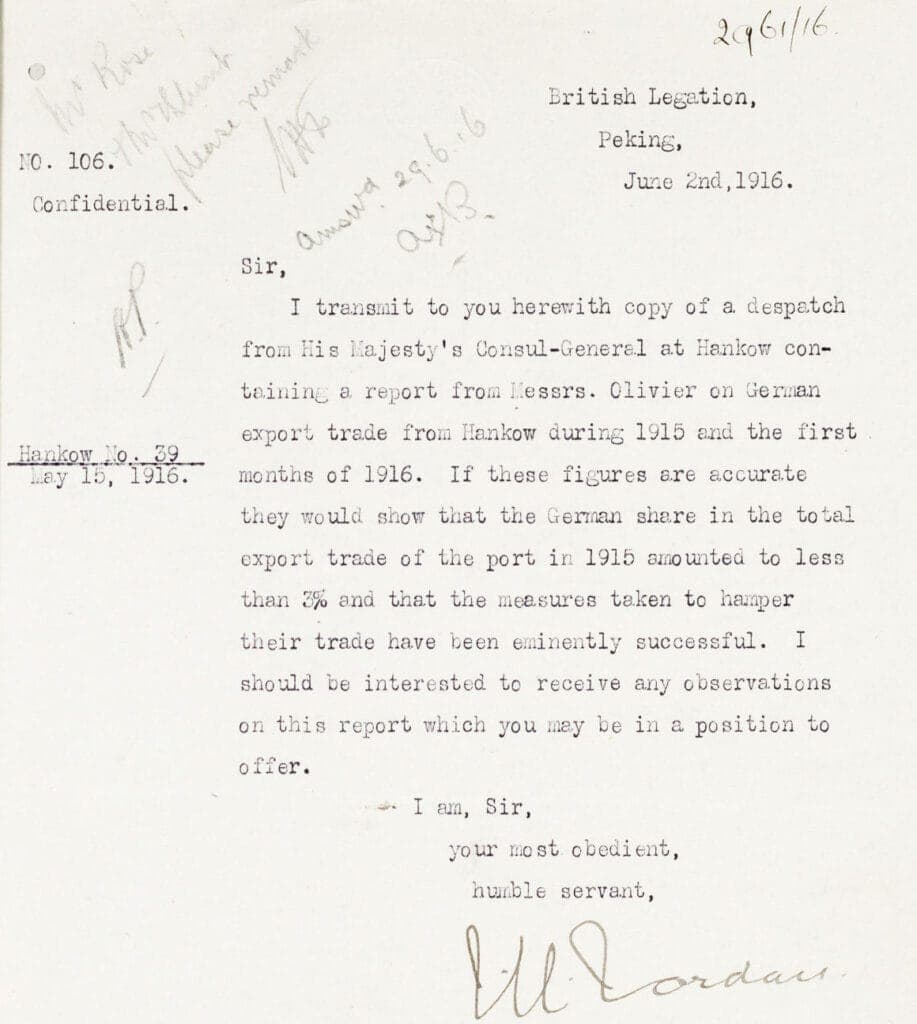

Restrictions were imposed on the trading activities of German firms too. For example, the report below illustrates the impact of such restrictive measures on the German export trade from Hankow in 1915 and the first months of 1916.

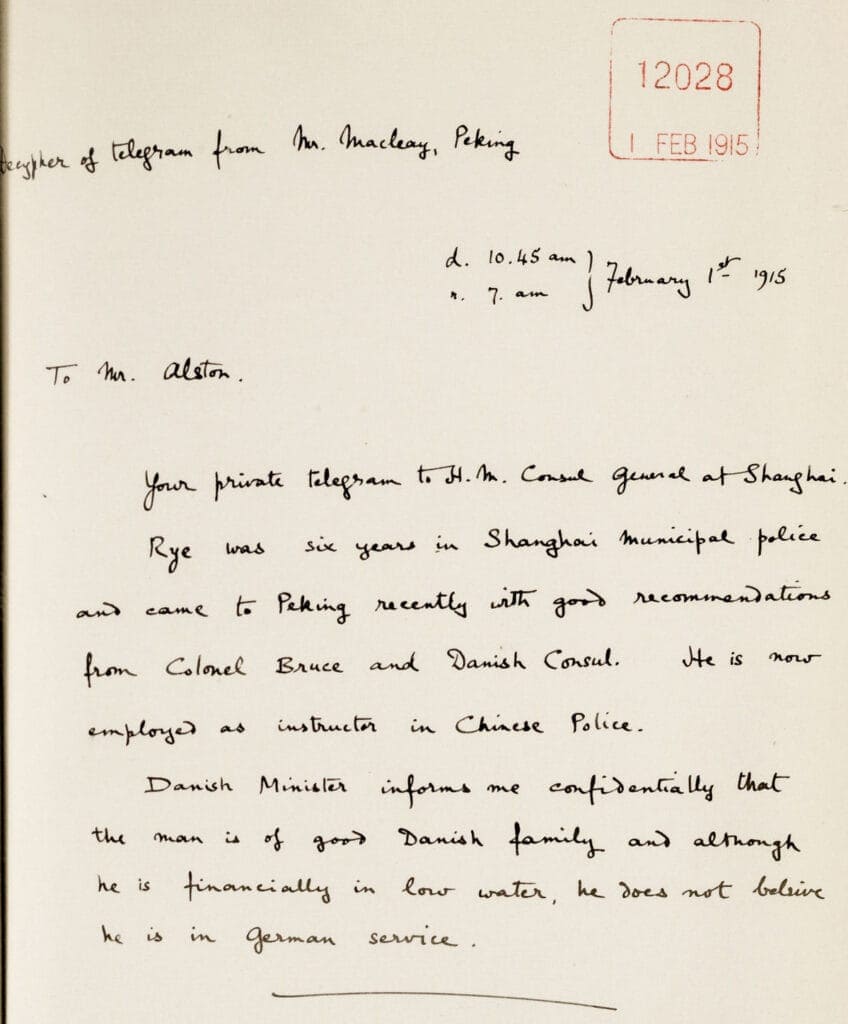

At the same time, actions were taken to investigate and monitor suspicious German spies. A Danish subject named Julius E. Rye, who worked for the Shanghai Municipal Police, was suspected of spying for Germany. However, after rounds of investigation, he was proven innocent with the help of the Danish minister based in Beijing as shown by the telegram dated February 1st, 1915 below.

Legal Affairs Concerning the British Expatriate Community

As the leading Western power in China from the mid-nineteenth century to the 1940s, Britain dominated almost every aspect of most, if not all, Chinese treaty ports with her subjects. Some of these British expatriates, including government representatives, police officers, businessmen, missionaries, and educators, were unavoidably implicated in numerous civil and criminal cases while in China, leaving behind many legal records.

These can be found in the general correspondence of the British Supreme Court for China based in Shanghai (FO656) and the notebooks authored by judges and magistrates sitting in the supreme, police, provincial, and summary courts at Shanghai (FO 1092). Such legal records provide a very interesting perspective on the daily life of the British expatriate community in China.

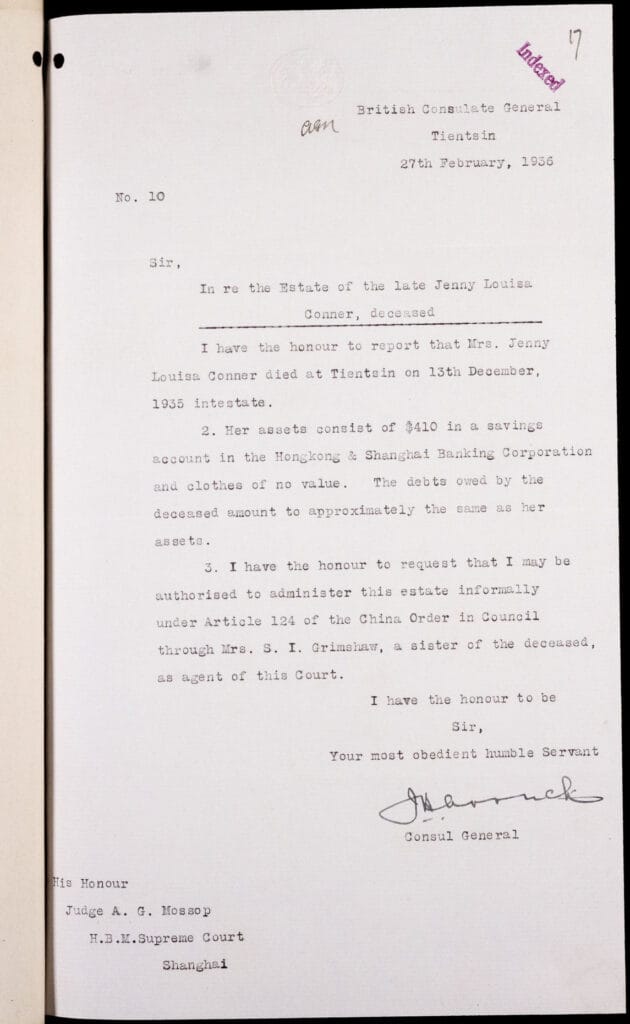

One major type of civil cases relates to the administration of the estates of British subjects who had passed away, without leaving behind any valid wills, in various treaty ports in China. The document below is a despatch, dated February 27th, 1936 from the British consul general at Tientsin reporting on the death of Mrs. Jenny Louisa Conner and the consul’s request for administering the deceased’s estimate.

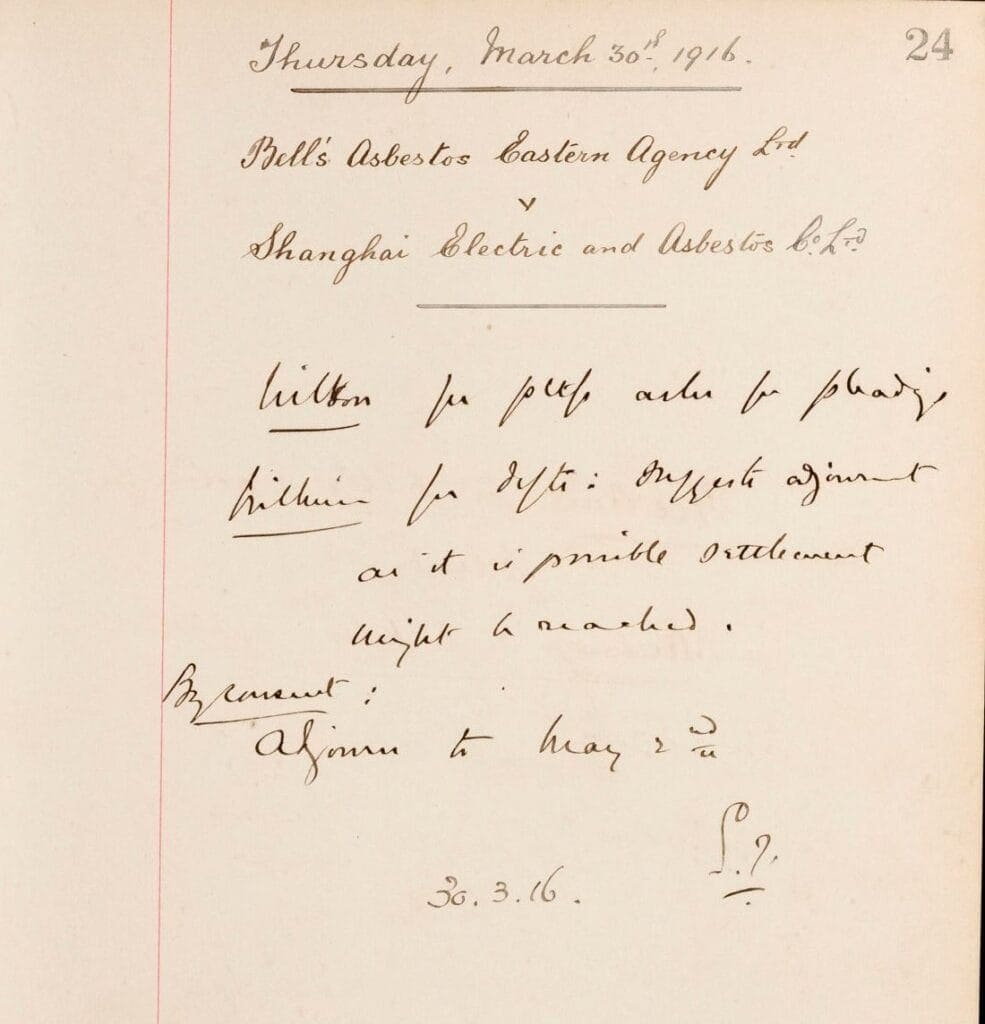

There are also cases involving business firms. For instance, the British Supreme Court heard a case concerning two companies, Bell’s Asbestos Eastern Agency Ltd versus Shanghai Electric and Asbestos Co. Ltd.

Sino-Japanese Wars

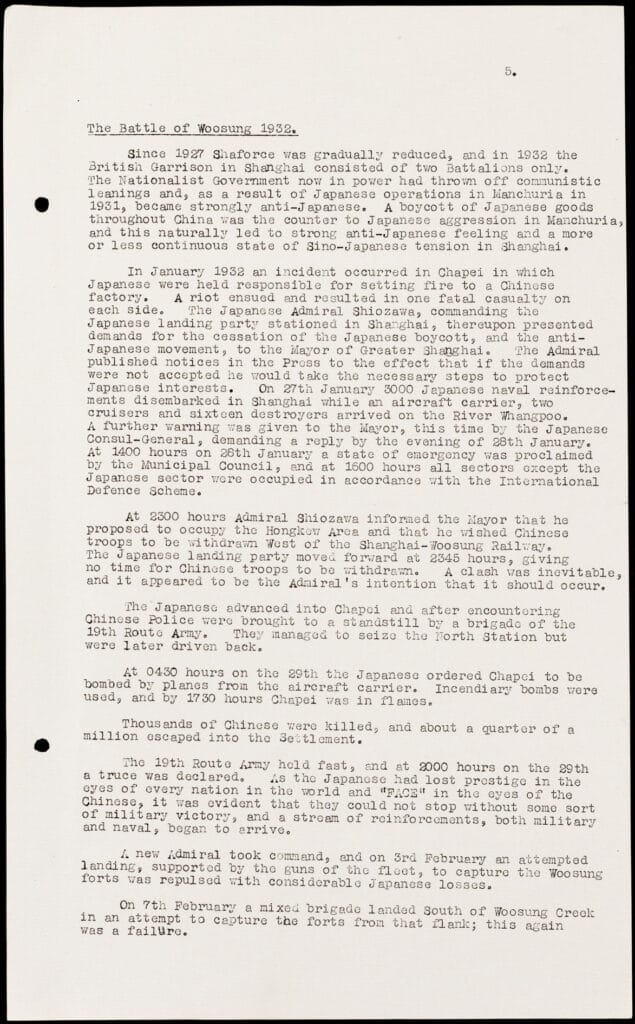

Prior to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937, the two East Asian countries had already gone through several armed conflicts. These include the Shanghai incident, or Battle of Shanghai, that lasted from January 28th to March 3rd, 1932. The incident had a direct impact on the Shanghai International Settlement due to its proximity to the war zone. Below is a page extract from an account by Brigadier Telfer-Smallett of the battle:

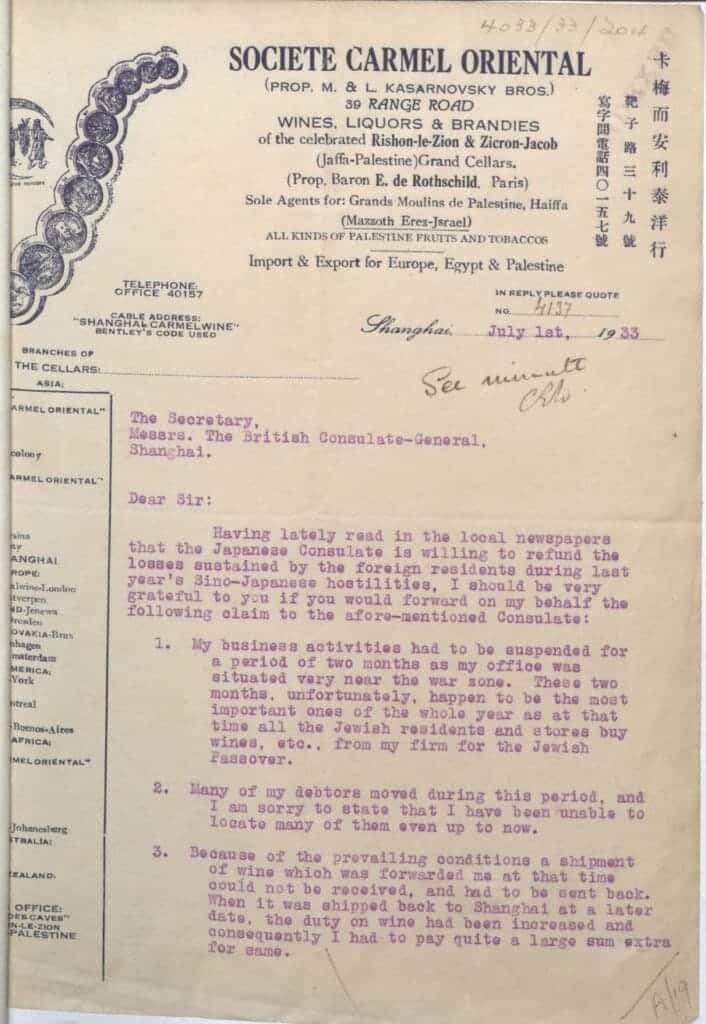

The conflict had caused damage to both the residents and businesses within the Settlement. FO 671 (Foreign Office: Consulate, Shanghai, China: General Correspondence 1845–1955) contains a volume titled “Claims arising out of Sino-Japanese hostilities.” Interestingly, in the volume is a case where Mr. Kasarnovksy from Societe Carmel Oriental, a wine and liquor agent and distributor, filed a claim amounting to M$8,000 against the Japanese government for losses suffered by him during the Shanghai Incident.

Related Gale Primary Sources Products

Over the years Gale has released many other Shanghai-related digital archive collections of varying sizes, providing a perfect complement to this thematic archive on the city. A range of these can be found in the Archives Unbound collections. Some, such as The Minutes of the Shanghai Municipal Council and Policing the Shanghai International Settlement, 1894-1945 include material produced by the Shanghai Municipal Council and the various municipal departments under it, shedding light on the workings of this self-governing body within the Settlement, which ran independently of both British and Chinese governments.

Other collections relate to the commercial, financial, social, and cultural aspects of Shanghai, like the Papers of Old Shanghai: Business, Banking and Insurance, 1874-1949 and Service Lists and Reports of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service and Whangpoo Conservancy Board.

If you enjoyed reading about the sources found in this archive, you may like to read the following posts:

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century, Part II

- Uncovering the History of Twentieth-Century Hong Kong, China, and the World

- Simla, McMahon, and the Origins of Sino-Indian Border Disputes

Blog post cover image citation: OVERSEAS: China (Code 0(J)): Shanghai International Defence Scheme. 1931. MS WO 32 War Office and successors: Registered Files WO 32/2534. China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/TCLKHE908007697/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=39265f65&pg=32.