│By Julia de Mowbray, Publisher at Gale│

Gale’s first online archive of British Colonial Office files, State Papers Online Colonial, has just been released. The first four parts1 will publish the Colonial Office (CO) files relating to the administration of Britain’s colonies in Asia, namely, Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak, Brunei, British North Borneo, Ceylon, and the naval base at Wei-Hai-Wei (Burma and India were administered by the India Office).

Part 1: Far East, Hong Kong, and Wei-Hai-Wei includes files from the Colonial Office’s general departments on Asia as well as the those from the administration of Hong Kong and Wei-Hai-Wei (Weihai). The Colonial Office general departments were the “Eastern” (1927-1951), “Hong Kong and Pacific” (1946-1955), “Far Eastern Reconstruction” (1942-1945), “Far Eastern” (1941-1967) and “South East Asia” (1950-1956) departments, spanning different periods, plus the early East Indies papers (1570-1856). These are joined by the Asia files from Confidential Original Correspondence, Confidential Print, Maps, Photographs series. In all it is around 385,000 pages. This part, therefore, is not limited to Britain’s colonies, but includes documents on China, Indonesia, Japan, and Korea. Each file is tagged with its subject country or countries to help researchers refine their search.

The Stories Within

Along with documents recording the major events such as English/British rivalry with the Dutch for trade in the East Indies, Britain’s early contact with China, Chinese-Japanese conflict, World War II, its aftermath and reconstruction, the development of industries and trade in commodities, and political changes and ideologies, are many documents recording every day or extraordinary events. Below I have picked out a few stories to provide a glimpse into the Asian world from the end of the sixteenth to mid-twentieth century.

Royal Correspondence

Picking up on the interest in all things royal of the last month, the early documents contain letters from:

- The King of Porqua (Purakkad, India) from 1592 (CO 77/1/9)

- Queen Elizabeth I of England to the Emperor of China (1596) (CO 77/1/11), and the King of Sumatra (1601) (CO 77/1/20)

- The King of Bantam (1605) (CO 77/1/25), the Great Mogul, Jahangir, Nur-Ud-Din Muhammad Salim (1618) (CO 77/1/67), Amer Ben Said, King of Socotra (1623) (CO 77/2/80), and Sultan Shahanshah, Shah Abbas I. of Persia (1626) (CO 77/4/3), to King James I of England

- King Charles I of England to the King of Bantam (1629) (CO 77/4/70), to Shah Safi I, and the Emperor of Persia (1630) (CO 77/4/80).

Later records contain announcements of deaths or coronations, or visits by members of the British monarchy, often recording how they are mourned or celebrated in the territories. There are some unexpected documents, such as one announcing the visit of the King of the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in April 1881: King Kalākaua was on a world tour to obtain labour from Asia to support his kingdom (CO 537/33/64).

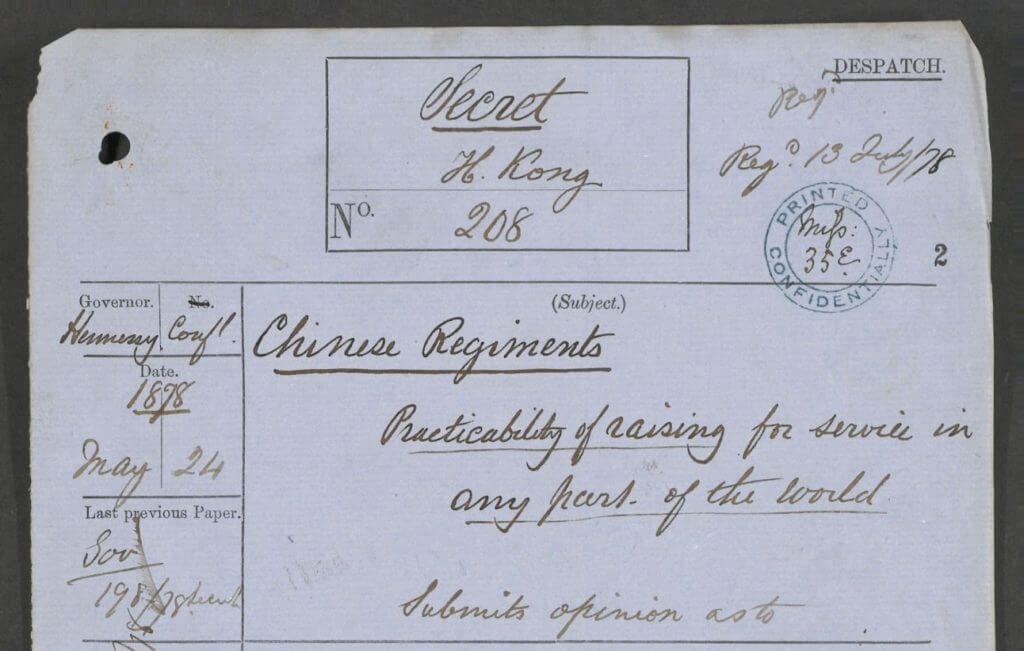

Recruiting Chinese Regiments to Defend Hong Kong

In 1878, it was expected that the defence of Hong Kong would be supplemented by soldiers sent across from India in the event of war. At that time Hong Kong had a police force of 650: 110 Europeans, 176 Indians, and 340 Chinese. In May 1878, the Governor of Hong Kong, John Pope Hennessey wrote to the Principal Secretary of State for the Colonies in London:

“2. Having had some experience of West Indian Regiments in Africa as well as in the West Indies and having also seen the value of other native Corps in different parts of the World, I believe the Colonies contain within themselves what might be made in every case efficient elements of defence, but in some cases also a not insignificant adjunct to the strength of the Regular Army.

3. Under European Officers, the Chinese would probably be found as amenable to strict discipline and as courageous in the face of the enemy as any Colonial Soldiers.

4. Though the Chinese who are residents under this little Government amount only to about one hundred and thirty thousand, yet the total number that pass through this Colony in a year cannot be far short of seven hundred thousand.

5. With a proper recruiting system I venture to think it might be possible to raise, at least, twenty thousand Chinamen of good physique, for service in India, or indeed, in any part of of the world. …”

(CO 537/184)

In a subsequent letter in June, he added that Colonel Donovan had also picked up the idea and that Colonel Bassano [?] had a high opinion of the Chinese:

“I find that Colonel Bassano[?], who has had four years experience of the Chinese in this Colony, entertains a high opinion of their soldierlike qualities. He thinks the Chinese we could recruit in Hong Kong would form native regiments more temperate, docile, and amenable to stricter discipline than any other native troops in Her Majesty’s service.”

(CO 537/187)

Sir Thomas Wade, then Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary and Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China, wrote a lengthy letter to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs on 28 September pointing out the various risks of the proposal including resultant complications between the Hong Kong and Chinese governments, and the ultimate loyalty of these Chinese servicemen when their families remained in China. However, he thought a Chinese Regiment deployed a long way from China could be a better option, and recruiting from the Straits Settlements rather than Hong Kong would be a better proposal (CO 537/202).

The idea was discussed in October 1878 by the Colonial Defence Committee and taken forward as a recommendation for the Gun Lascar Force to be supplemented by Chinese enlisted in the Colony. A Chinese Regiment for Hong Kong was not finally created until 1941, just before the Battle of Hong Kong, only to quickly disperse following the surrender to the Japanese. One was also created in Wei-Hai Wei in 1899 but that was disbanded in 1906.

Gaspin Coup, Seoul

Among the confidential documents are some relating to the Gaspin Coup which took place in Seoul on December 4, 1884. Following the failure of the coup, several of the leaders sought exile in Japan, including one of whose ministers had initially supported the plot. Just over a year later, in a cyphered telegram, the Japanese government asked whether Kim-Ok-Kiun, one of the leaders of the insurrection, could be transferred to Hong Kong. It proposed “sending him to Hong Kong where he might still be watched. China objects to his being sent to America whence he might reach Siberia secretly and help the Russians. Will Her Majesty’s Government allow him to remain in Hong Kong?” (CO 537/33/124). Her Majesty’s government declined.

The Griffin Mission

Allen Griffin appears in the September 1948 intelligence survey of the British Consulate-General, Canton, as a visitor from 17 to 21 September in the company of Mr R. Lapham, Director of the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) China Mission. It states they visited Whampon (CO 537/3327). The second appearance is the following year in Shanghai in a Reuter’s cable of 28 April:

“The China Mission of the Economic Cooperation Administration announced today that it was prepared to support the operation of mills in Shanghai with American Aid Cotton as long as the harbour was open and the city was not under communist control. Mr R. Allen Griffin, Deputy Chief of the Mission, said there were 42,000 bales of American Aid Cotton in the City ready for distribution to mills. He wished to correct any misapprehension that the ECA was abandoning the cotton programme for Shanghai. Reuter 1359.”

In another Confidential file entitled “International Relations. Foreign Affairs: Indonesia”, and dated 1950 (CO 537/5753), a year after the Dutch conceded to Indonesian independence, is a reference to Griffin recommending an economic aid package to Indonesia. On 16 October, the United States Information Service announced at Djakarta an agreement providing for economic cooperation between the Republic of Indonesia and the United States of America. It stated that the agreement arose from recommendations made by the economic survey mission led by Mr R. Allen Griffin which had visited Indonesia that April. Assistance would be made in the form of supplies and technical advice in the fields of public health, agriculture, fisheries, industry and education. $11.5 million was anticipated being allocated.

Also in 1950, the UK government prepared a 71-page memorandum for Mr Griffin that outlined the economic situation of the Federation of Malaya, the heavy costs incurred by the British government following the war, and possible areas and considerations for Economic Cooperation Funding (CO 825/90, Part 2). Griffin visited other countries in the region, such as Thailand, Singapore and Myanmar. On 21 October, Griffin was appointed director of the Economic Cooperation Administration’s Far East Division.

In the announcement, Griffin was quoted as saying “The people of Asia do not want to become the economic wards of the United States. We can succeed in winning their friendship only by demonstrating our willingness and capacity to assist their governments, so that the people will themselves feel the benefits of a national government that elevates their pride and lessens their hardships, it is a job for practical, far-sighted, and hard-working men to labour to meet the aspirations of these people – their aspirations for themselves, not ours for them” (CO 537/6102). Certainly, their governments needed economic and technical assistance plans to help overcome the turmoil and destruction of the Second World War. The ECA was not the only support scheme for Southeast Asia at the time. The Colombo Plan was a Commonwealth initiative, and there were some others.

Case Study: A Year in the Life of … British Rule of Wei-Hai-Wei

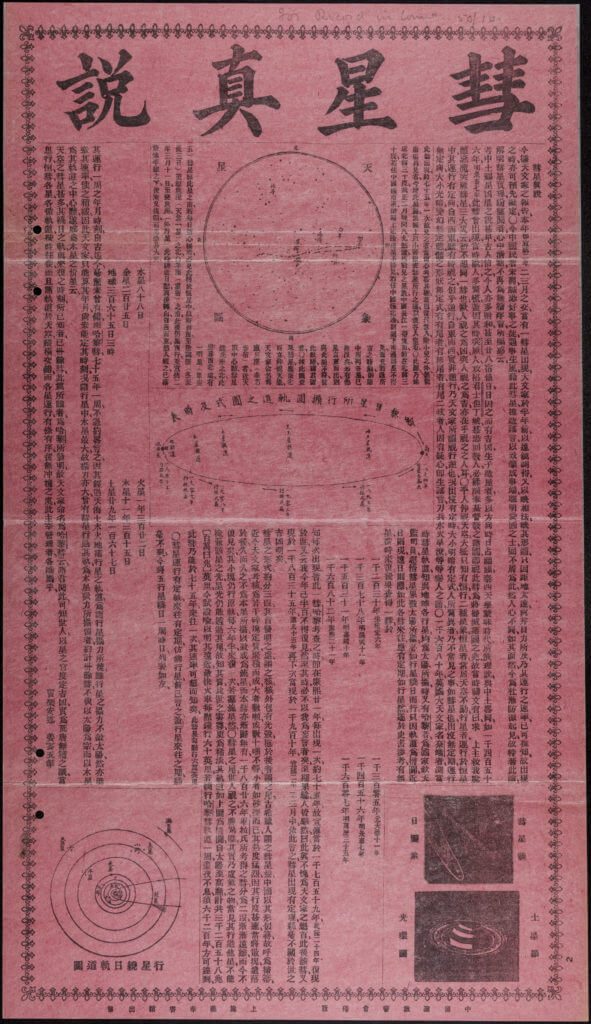

The content also lends itself to many case studies about daily life through the period. As an example, I had a look at documents covering Wei-Hai-Wei from one year, and that year is 1910, a year Halley’s Comet was seen.

Many peoples, including the Chinese, saw the appearance of Halley’s Comet as a sinister omen or at least preceding dramatic change. Is it a coincidence that in following year China experienced the Xinhai Revolution, ending 2,000 years of dynastic rule?

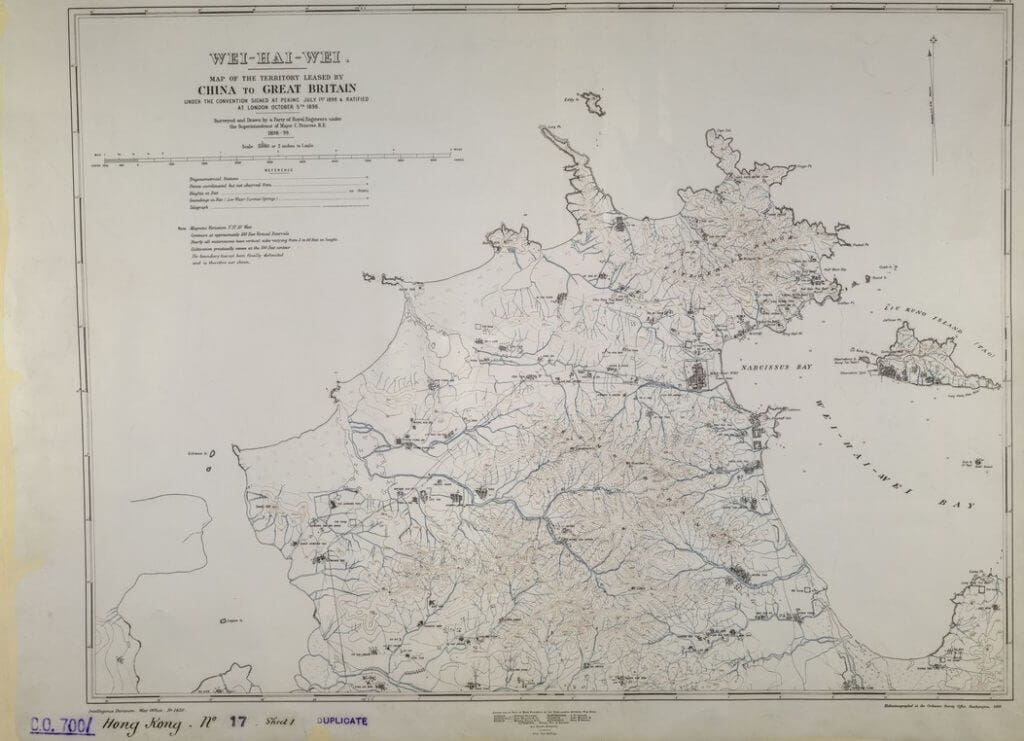

While Hong Kong was important to Britain, not just for its strategic position in Asia, but mostly for its value as a trading port, becoming one of the world’s most important centres of business, finance and commerce, Wei-Hai-Wei was only of interest as the site for a naval base. It had been the base for the Beiyang Fleet during the Qing Dynasty but had been captured and occupied by the Japanese from 1895-98. While the Russians obtained a lease on Port Arthur for 25 years in March 1898.

Wei-Hai-Wei, the port, near Yantai, in Shandong province, on the Yellow Sea facing Korea, was leased by Britain from China in 1898 for use as a naval harbour administered by a senior naval officer. In 1901, control passed to the Colonial office until it was returned to the Republic of China on October 1, 1930, while retaining Liugong Island and its facilities until 1940. Port Edward was its capital city. During the British administration, residences, hospital, churches, tea houses, sports ground, post office, and a naval cemetery were constructed.

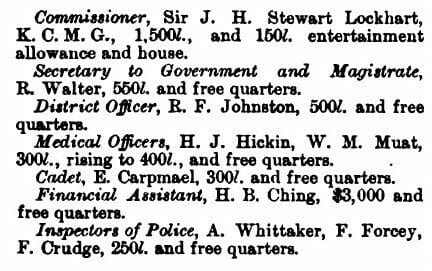

The administrators of Wei-Hai-Wei for 1910 are listed in that year’s Colonial Office List. The entry also gives a history and description of the territory, a brief note on the climate “one of the best in China”, and a section on the constitution and government. We learn that there are around 310 villages, a population estimated at 150,000 and that the village communities are administered through their headmen in accordance with Chinese custom.

Looking through the 73 files and 2 registers of letters in the Wei-Hai-Wei series2 the subjects can be sorted into administration (finance, tax, census, reports), issues (opium, Transvaal) and diplomacy (visit of the new governor of Shantung).

Opium

The previous year, 1909, Ordinance no 1 prohibited people “to import, export, possess, sell, or buy any opium (including morphine) or other hypnotic (including cocaine)” (CO 882/9/7) except for medics and chemists for medicinal reasons. Opium divans or dens were prohibited.

On 20 January 1910, Inspector Crudge, one of the Inspectors of police (listed in the table above) sent a report to R. Walters, Secretary to the Governor, on opium smoking in the territory. He said that from his investigations and visits to six opium establishments where he found from 30 to 40 natives, some from Tientsin, Man-Chu-Tao, the Island and Port Edward, it was evident that opium smoking was widespread. A daily report was requested. By 26 January, the magistrate issued a proclamation stating that anyone wanting to smoke opium must obtain a licence, available only from Kuang Kau Chu’s licensed shop, and each restricted to one lamp and one pipe. By early February, 35 licences had been procured.

With the help of dedicated opium detectives, the amount of opium sales dropped until the remaining shop was closed. On 29 March, the Commissioner, Sir James Lockhart, started an investigation into raw opium, whether it is sold in the territory, how opium was produced, weighed and accounted for. This included samples prepared under police supervision. The reports from R. Walter contain details of the variations in preparing and measuring opium, the differences between how the two establishments in the territory prepare and measure their opium and that detailed by a Mr Clementi who had prepared a confidential report on opium in Hong Kong (CO 873/298).

By April, the Commissioner was challenging a libellous newspaper article published in a Chinese newspaper, “Illegal conduct of the British Authorities” in Po Hai Jih Pao, on May 1st 1910 (CO 873/301). The article starts:

“In the leased Territory of WEIHAIWEI the British authorities UNDER THE PRETEXT OF ASSISTING US (the Chinese) IN THE PROHIBITION OF OPIUM are making indiscriminate SEARCHES, Anybody who has a little property is informed against as an opium smoker and is COMPELLED TO PAY A FINE. Every two or three days a house to house SEARCH is made, and if once an opium pipe needle is found the fine inflicted is FIVE dollars: if an opium pipe bowl is found the fine is FIFTY dollars, while for a pipe the fine is ONE HUNDRED dollars. The fines recently inflicted in one day would actually fill up two cases of Kerosene oil. That the British authorities secretly “plant opium” is clear.”

A second article was entitled “Note on the Harsh Treatment of Chinese by the British Authorities at Weihaiwei.” Lockhart contacted R.H. Mortimore, HM Consul at Chefoo, and W.G. Max Muller, H.M. Charge d’Affairs, Peking, to pressure the Chinese officials to prosecute the publishers. A telegram of 15 May from Mortimer informed him that the editor of the Po Hai Jih Pao has been tried for libel with the proposed sentence to be the suspension of the newspaper for a week. Two other newspapers were pursued for the same libel, the T’ien To Pao and the Shên Chou Pao. The file contains examples of the newspaper articles, translations into English, and newspaper clipping in English of the episode.

The Transvaal

Throughout the year, there was a regular correspondence about accommodating Chinese convicts from the Transvaal. For some context, a file from 1904 contains the communications between the Commissioner of Wei-Hai-Wei and the Governor of Shantung about a proposal to offer of Wei-Hai-Wei as a port of embarkation for Chinese emigrating to the Transvaal to work in the mines. The Chinese Governor was reported by R.F. Johnson to have been in favour of such emigration as it would enable “the very large surplus population to earn an honest and comfortable livelihood.” It was stated that Manchuria was no longer desirable due to Russian oppression, and also that the Governor was shocked that no one in the administration had visited and viewed the conditions for the workers in the Transvaal personally. It looks as if an inspector of labour was engaged a little after this. However, political changes in South Africa leading up to the Union of South Africa in 1910, resulted in a gradual repatriation of Chinese workers, and with Britain asked to take responsibility for all existing Chinese convicts in the Transvaal.

The 1910 files concern the finding of accommodation for the convicts and the costs of providing it. Forty convicts were expected, twenty of whom were on life sentences. More detailed costings for a new gaol were supplied in a letter of 9 June (CO 521/11/38). By August came the news that the Government of South Africa had recommended that the convicts be discharged as an act of clemency, meaning the new gaol would no longer be required (CO 521/11/45). By the end of the year, Wei-Hai-Wei was left trying to gain compensation for the work executed on the new gaol. A report written by the Financial Assistant, Mr H. B. Ching, to support the claim details the whole year’s saga with all the costs (CO 521/11/60).

The Chinese Census

On January 15, 1910, the Chinese governor of Shantung informed the Commissioner that he wanted to include people of Wei-Hai-Wei in the forthcoming Chinese census. The British administration discussed concerns that that if Chinese officials were seen conducting the census within the British-administered territory, false rumours about an imminent return of the territory to China would circulate. The officials contacted the German government to find out how they were responding, but the latter had not been contacted although they had a similar situation at Kiaouchau. It was decided to inform the Chinese Governor that the British were planning their own census in next year in connection with the general census of the Empire, and that they would then be happy to furnish any information the governor should require. An ordinance, no 2, 1910 (CO 521/11/58) was created to enable the census, and another episode concluded.

Halley’s Comet

Halley’s comet is seen only every 75 years. Between 20 April and 20 May 1910 was one such occasion. The British administration at Wei-Hai-Wei was pleasantly surprised to see a leaflet created by Chinese authorities on the comet for the local public. Additional copies were requested and posted on government notice boards and on the city gates. The Secretary to the Government, R. Walter, commented that some people in China and Europe saw the comet as a having sinister influence, and in China it was viewed as an unlucky omen, indicating calamity such as war, fire, pestilence, or a change of dynasty. The Qing dynasty ended less than a year later.

If you’re interested in the history of Hong Kong and China, you may like:

- The History of Extradition in Hong Kong

- Discover the History of British Hong Kong Through Handwritten Documents – Now Available in “Easy Mode”!

- Tears, Cheers, The Archers, and Soy Sauce: The Hong Kong Handover of 1997

- The Rise and Fall of Chinese Indentured Labour

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

If you enjoyed reading about State Papers Online, you may like:

- How State Papers Online Can Support an Undergraduate History Dissertation

- New State Papers Online Experience Available to Preview

- State Papers Online Eighteenth Century, Part IV: Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Turkey

- Here Comes the Sun King: finding Louis XIV in State Papers Online

- State Papers Online Colonial: Asia will be published in four parts:

I. Far East, Hong Kong, and Wei-Hai-Wei

II. Singapore and British Borneo (Singapore and East Malaysia)

III. Malay States, Malaya, and Straits Settlements (West Malaysia)

IV. Ceylon (Sri Lanka) - Colonial Offices series CO 521: Wei-Hai-Wei Original Correspondence, CO 873: Wei-Hai-Wei Commissioner’s Files, 1899-1930, CO 770: Wei-Hai-Wei Register of Correspondence, 1898-1931, and CO 771: Wei-Hai-Wei Register of Out-letters.