│Liping Yang, Senior Manager, Academic Publishing, Gale Asia│

Siam (now known as Thailand) had long been a tribute nation of China’s Qing empire. However, the signing of the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce between Great Britain and Siam in 1855 opened a new chapter in the history of this Southeast Asian nation and its relationship with China and Western powers represented by Britain. This blog post retells the interesting stories behind the signing of this historic treaty through some invaluable primary source materials discovered in China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part 1, 1815-1881.

Background

Until the mid-nineteenth century, Siam was a highly inward-looking dynastic kingdom ruled by the Chakri dynasty since 1782. Like China’s imperial Qing dynasty, the Siamese royal government adopted a rather conservative, restrictive, and even antagonistic policy toward trade and communication with the West. Foreign trade was monopolised by the royal household, with foreign merchants in Bangkok being subject to all kinds of restrictions and prejudices. Most of the time, they could only stay within the so-called “factories,” small areas marked out by the local government for foreign business activities.

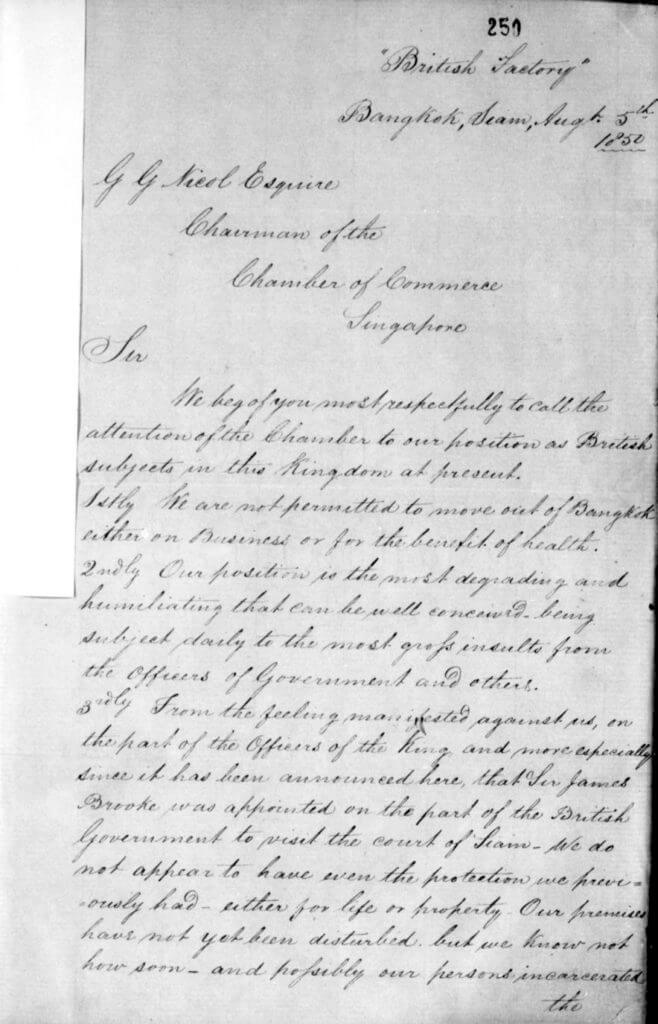

The British merchants operating in the British Factory were affected by this adverse atmosphere the most. On August 5, 1850, representatives of Messrs. Brown Brothers and Co. wrote a letter from Bangkok to the chairman of the British Chamber of Commerce in Singapore, complaining about their unpleasant and even dangerous experiences at Bangkok such as “not [being] permitted to move out of Bangkok either on business or for the benefit of health,” “being subject daily to the most gross insults from the Officers of Government and others,” and “possibly our persons [being] incarcerated.” They felt so vulnerable that they appealed for the British royal navy to “send a man of War off this bar immediately, to protect our lives and property.”

Dr. Gutzlaff, Mr Parkes, Mr Gingell, Consular Appointments, and Foreign Various. 1850. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/171. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CCTSDA528247453/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=00f103c7&pg=252

To resolve the situation, the British government first sent Sir James Brooke (1803 –1868), British Raj of Sarawak, to Bangkok in 1850 to negotiate a commercial treaty with Siam, but the negotiations ended badly.

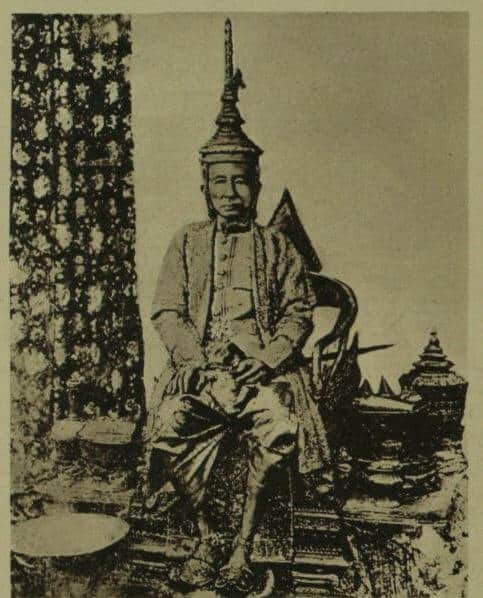

A new opportunity presented itself in 1851 when Mongkut succeeded to the throne as the new king of Siam (aka, King Rama IV, 1851–1868). King Mongkut was a well-educated and reform-minded monarch who could speak and write English and was fascinated by Western material and technological progress. He was keen to improve Siam’s relationship with Britain and other Western powers.

Chula, H. R. H. Prince. “A Prince of Siam at Home and Abroad.” Illustrated London News, 9 Feb. 1957, p. 222. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HN3100381262/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=5585974b

In July 1852, Mongkut dispatched a tribute mission to China in the hope of obtaining from the Chinese emperor formal confirmation of his succession to the throne. The Siamese mission reached Hong Kong on August 28 and received a warm reception by Sir John Bowring (1792–1872), who was then chief superintendent of British trade in China and acting governor of Hong Kong during the absence of Sir George Bonham.

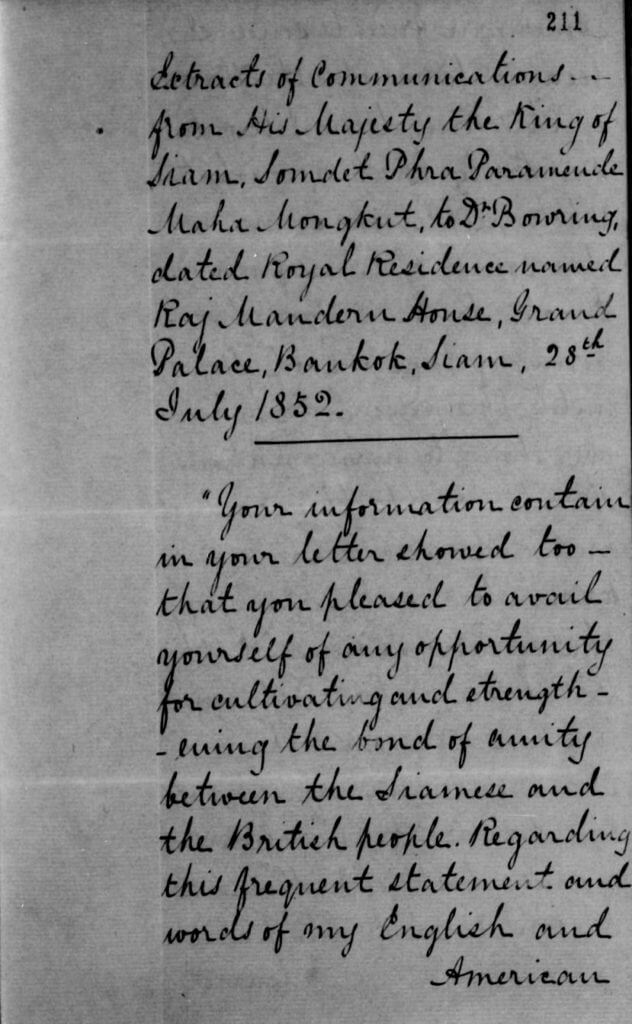

In the autograph letter addressed to Bowring, Mongkut demonstrated his awareness of the Wester powers’ activities and interests in India and other parts of Asia and expressed his interest in making “any connection of this country with all white people who are mariners or merchants of their Colonies.” He welcomed Bowring’s intention to visit Siam with a view to “cultivating and strengthening the bond of amity between the Siamese and the English people,” but also stressed that Siam should be treated equally as Cochin China [now Southern Vietnam].” All this was recorded in a despatch and inclosure dated August 30 and July 28, 1852, respectively, from Bowring to British Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Malmsbury.

Dr. Bowring and Sir S. G. Bonham. August-September, 1852. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/192. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EJEZGO204269624/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=a432d3a2&pg=211

Having felt the sincerity of King Mongkut’s invitation, Bowing proposed in September 1852 to the Foreign Office to pay an official visit to the Siamese court for negotiating a commercial treaty, which was approved in November.

Arrival of the Bowring Mission at Bangkok

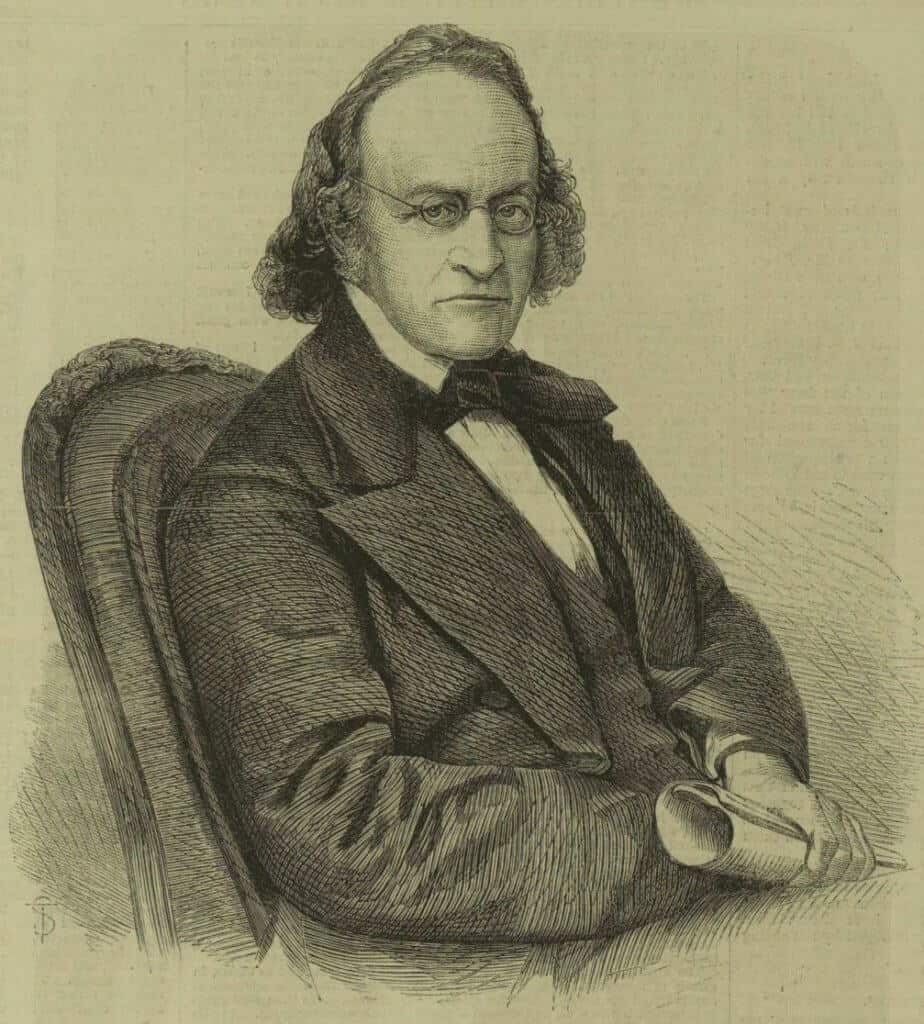

“Mr. Commissioner Parkes.” Illustrated London News, 22 Dec. 1860, p. 587. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HN3100526539/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=48938290

The intended visit to Siam did not take place until after John Bowring was appointed Governor of Hong Kong and British Government’s Plenipotentiary in January 1854, while at the same time retaining the position of chief superintendent of British trade in China. The British mission—consisting mainly of John Bowring and Harry Parkes (1828–1885), then British consul at Amoy—embarked on its voyage on March 12, 1855, heading toward Bangkok on board two British naval vessels, the Rattler and the Grecian under Captains Mellersh and Keane, respectively. The mission arrived at Paknam, the mouth of Chao Phraya River on April 2, and then Bangkok on April 3. Members of the mission lodged at the British Factory. While waiting at Paknam for the Rattler to pass the bar, Bowring received a series of welcome letters from King Mongkut who also made sure the British mission was furnished with a vast variety of food and fruits.

![A page from “Despatch Number 144: Details of His [Bowring’s] Reception & Mode of Conducting Treaty Negotiations at Siam” on Bowring receiving the King’s communications.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/6.BowringReceivingKingsWelcomeLetters-1024x842.jpg)

Sir J. Bowring and Mr Woodgate. April 9-May 9, 1855. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/229. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CLLXHJ452396853/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ee58fc9a&pg=139

Bumpy Yet Smooth Negotiations

Given the wide cultural differences, the British representatives and the Siamese government found it hard to agree on some matters. For instance, Bowring wanted the Rattler to follow him to Bangkok and fire a Royal salute upon arrival. However, this request encountered resistance from the King and his nobles who feared that would frighten the people and cause misunderstanding about the mission’s object. The two sides eventually agreed to delay the firing till after the King issued a public proclamation on this.

![A page from “Despatch Number 144: Details of His [Bowring’s] Reception & Mode of Conducting Treaty Negotiations at Siam” on the two sides’ disagreement on the firing of salutes.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/7.-A-page-from-Despatch-Number-144-combined.jpg)

Sir J. Bowring and Mr Woodgate. April 9-May 9, 1855. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/229. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CLLXHJ452396853/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ee58fc9a&pg=141

Discussion on the Bowring mission’s public reception by the King was also not an easy one. It was postponed several times for religious and other considerations before it was confirmed to take place after the negotiations were completed. The two sides also spent a lot of time talking about the appropriate protocols to be followed during the mission’s reception by the King. While Bowring agreed to “implicitly obey the King’s orders,” “in matters where my Sovereign’s dignity was concerned, I would surrender nothing, that the right of wearing the full costume with the sword had been conceded by the King of Siam to Monsieur Chaumont, the Ambassador of Louis the fourteenth – and I produced the record as indisputable evidence of the fact.” Luckily, the Siamese King was very kind and agreed “not deny to me the honor of appearing in his presence exactly as we should appear at the Court of our own Gracious Queen.”

During Bowing’s first interview with the King on the evening of April 4, 1855 the King told him that “he knew Siam was weak and we were strong. He was kind enough to speak of me as of a ‘dear friend and old acquaintance’ and said he should have been greatly disappointed had I not come.” So it looks as if the forthcoming treaty negotiations would sail through. However, that was not the case.

![A page from “Despatch Number 144: Details of His [Bowring’s] Reception & Mode of Conducting Treaty Negotiations at Siam” on Bowring’s first interview with the King of Siam.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/8.BowringInterviewwithKing-1024x852.jpg)

Sir J. Bowring and Mr Woodgate. April 9-May 9, 1855. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/229. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CLLXHJ452396853/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ee58fc9a&pg=146.

To facilitate the negotiation, the Siamese government set up a commission of five senior officials, including the King’s brother “Prince Krom Hluang Wongsa . . . the supreme and second regents of the Kingdom [Somdetch Chau Phaya Param Maha Puyurawongse and Somdetch Chau Phaya Param Maha Bijaineate], the Phrakalahome (Prime Minister) and his brother, the acting Phra Klang or Minister for Foreign Affairs.” The negotiations started on April 9, 1855 (Monday) and ended with the two sides agreeing to meet again the following Wednesday to discuss the difficult terms relating to tariffs and duties. However, something unexpected happened: The Senior Somdetch fell ill, and others could not attend the scheduled meeting with other excuses on the morning of Wednesday. Even the Prime Minister himself also cancelled his meeting with Bowring and Parkes, saying “that unexpected difficulties had presented themselves, that there was an unwillingness to move, and that he was absolutely worn out with exertions, annoyances, and impediments.”

![A page from “Despatch Number 144: Details of His [Bowring’s] Reception & Mode of Conducting Treaty Negotiations at Siam” on the Siamese commission and the start of negotiation.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/9.SiameseCommissionStartNego-1024x856.jpg)

Sir J. Bowring and Mr Woodgate. April 9-May 9, 1855. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/229. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CLLXHJ452396853/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ee58fc9a&pg=148

In view of this tricky situation, Bowring threatened not to “fulfill the promise I had made to the king that the steamer should drop down during the religions ceremonies of the following day, that neither I nor my suite would attend those ceremonies which on the King’s invitation, we had intended to do.” This worked and the negotiations were resumed on April 13, with the two sides going through rounds of hard bargaining on whether specific articles, e.g., dried fish, salt, and rosewood, should be included in the list for tariff and duty reduction, as well as whether and how to “limit the right of ships of war coming to the city of Bangkok.” The meeting lasted from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and ended with the two sides agreeing on all the terms of the treaty. The English version also obtained the King’s approval on the very evening. On April 18, 1855 both the English and Siamese versions of the treaty were signed and sealed at 2 p.m., which was announced by “a Royal salute from the Rattler, which was responded to by the forts.”

![A page from “Despatch Number 144: Details of His [Bowring’s] Reception & Mode of Conducting Treaty Negotiations at Siam” on the signing and sealing of the treaty.](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/10.treatysigningsealing-1024x855.jpg)

Sir J. Bowring and Mr Woodgate. April 9-May 9, 1855. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/229. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CLLXHJ452396853/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ee58fc9a&pg=153

At the same time, more than one grand public reception was conducted for the British mission as a full manifestation of the King’s hospitality toward Bowring and his suite. Additionally, the King and his brother, the Second King, also met Bowring privately a few times after the treaty was finalised to express their sincere hope of maintaining a good relationship with Britain.

Having fulfilled the object of the mission, Bowring and his suite departed from Bangkok on April 24, 1855 with “the Royal Letters and presents.” Parkes went on to Britain with the Treaty for it to be ratified by the British government. He exchanged the ratified Bowring Treaty in Bangkok on April 5, 1856.

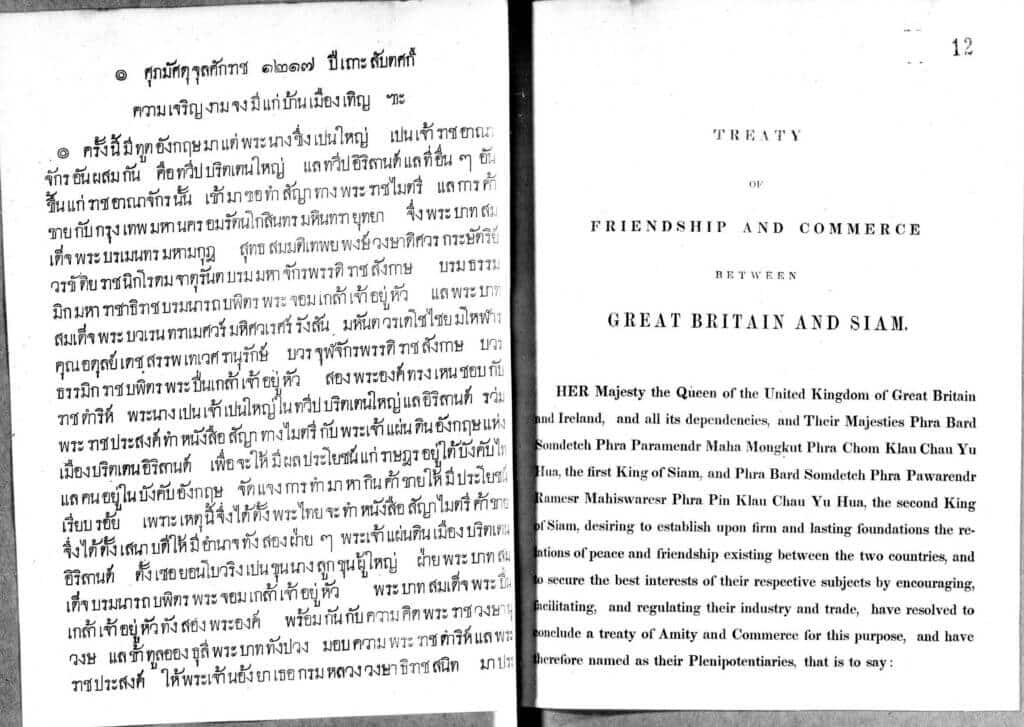

To Sir J. Bowring. June 1857. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/270. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BRYLWV152041320/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=8fcb306b&pg=12

Main terms and aftermath of the Bowring Treaty

The treaty of amity with Siam was negotiated by Sir John Bowring as the British government’s plenipotentiary and is now often referred to as the “Bowring Treaty.” Similar in nature to the unequal treaties signed between China’s imperial Qing dynasty and Western powers after the First and Second Opium Wars (1839–1842; 1856–1860), the Bowring Treaty played an important part in liberalising Siam’s foreign trade and stimulating its economic rejuvenation through a legal framework that guaranteed the unrestricted operation of multilateral trade in Southeast Asia and with China. Among the treaty’s key terms are:

- British subjects in Siam were granted extraterritoriality, which prevented them from being prosecuted by local Siamese authorities.

- British subjects were allowed to travel freely in the interior, trade freely in all seaports, and reside permanently in Bangkok where they could buy and rent property.

- Import and export duties were fixed, and opium trade was legalised.

- Export articles could be taxed just once, whether the tax was called an inland tax, a transit duty, or an export duty.

- British merchants were allowed to trade directly with individual Siamese subjects.

- The Siamese government reserved the right to prohibit the export of salt, rice, and fish.

If you enjoyed reading about the Bowring Treaty of 1855 and the opening up of Thailand, you may like:

- Ernest Satow’s First Audience with the King of Siam

- Ngiam Tong-Fatt’s Essays Provide Great Insight into Mid-Twentieth Century Southeast Asia

- Western Books on Southeast Asia Collection

- The Chinese diaspora during China’s transformation from Empire to Republic: experiences in five different regions

To learn more about the content in Gale’s China and the Modern World archive series, try:

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- George Macartney, Kashgar and the Great Game

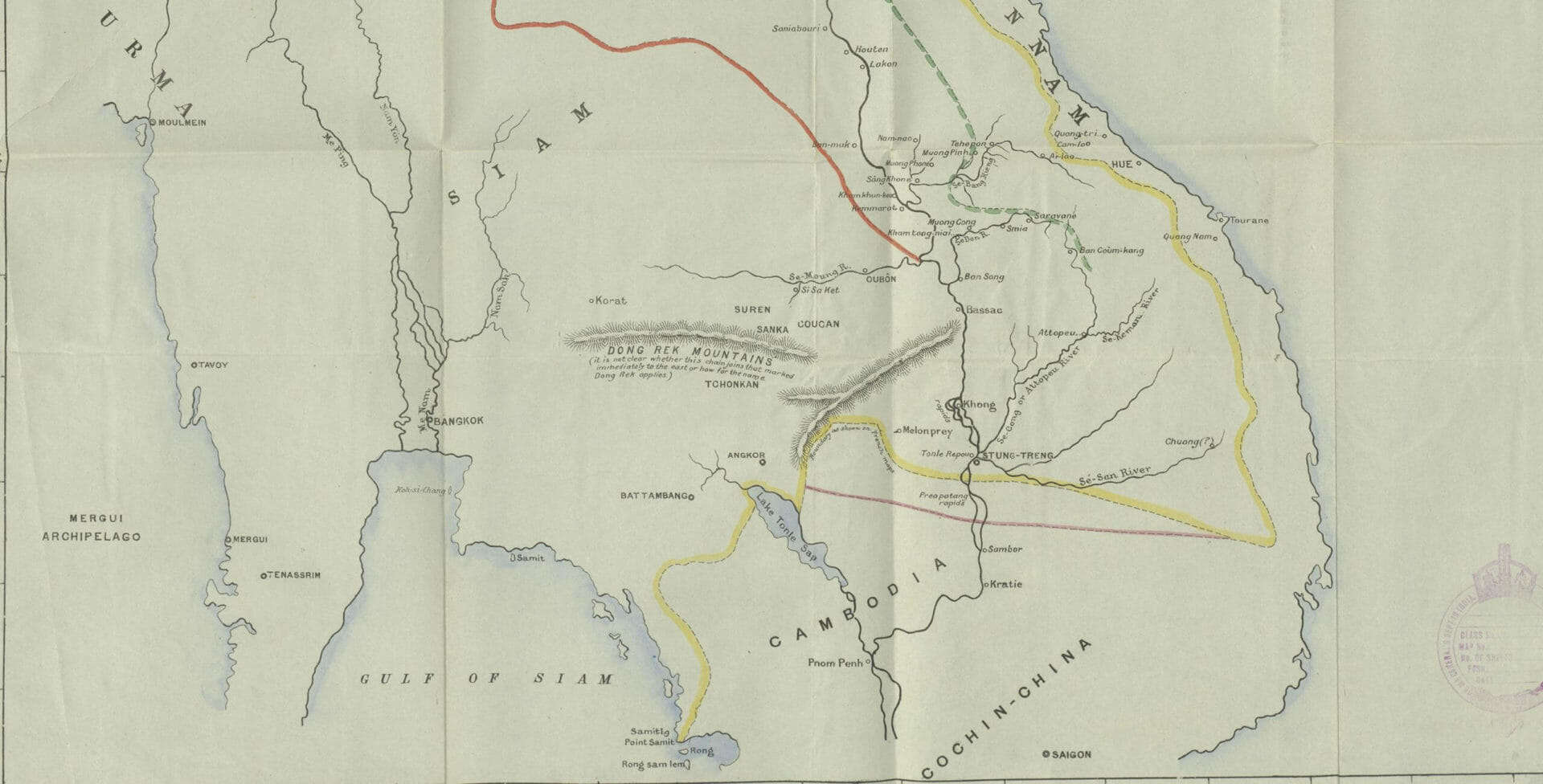

Blog post cover image citation: Affairs of Burmah, Siam; French Proceedings Etc. Volume 22. August 16-31, 1893. MS FO 17 Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence, China FO 17/1183. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/GNUEKQ428557079/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=d56413ce&pg=159