│By Mo Clarke, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter│

Disabled. A word many find uncomfortable. Indeed, it seems much of society still assumes that to be disabled is to be broken, but while it is true that many people with disabilities experience ableism and insufficient support, resources and facilities, activists have long fought against the presumption that to be disabled is inherently bad. Rather than a curse or insult, their disability is a part of their identity and a source of pride. Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender reveal that disability rights have also been a focus for another minority group in the United States: the LGBT+ community. In the 1980s and 1990s LGBT+ activists made great strides towards improving the lives of disabled people.

The History of Disability Rights Activism

Disability rights activism took off in the United States in the latter half of the twentieth century, influenced by a variety of factors. Post-WWII, disabled veterans placed pressure upon governments to provide rehabilitative support and facilities and brought disability rights into public view. The civil rights movement of the early 1960s brought the opportunity for intersectional activism; activism which encompassed numerous minority groups who fought for recognition and equality. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 introduced legal protection for people with disabilities, prohibited discrimination and mandated equal access to public resources and services. Campaigning continued throughout the 1980s – including activism by the LGBT+ community – and in 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed, further ensuring equal treatment and access. There was still work to be done, however, and activists continued to fight to improve the lives of people with disabilities for the next thirty years.

Pride

Like the LGBT+ community, people with disabilities have fought for an end to the assumption that they should be ashamed or hidden. Pride events where LGBT+ people could be open about their sexuality and defend their rights began in the early 1970s in New York’s West Village after the events of the Stonewall Uprising in 1969. LGBT+ disability activists encouraged disabled pride events which allowed people with disabilities to express themselves and assert their right to inclusion within society. America’s first ever Disability Pride took place in Boston in 1990, where over 400 people “marched, drove, wheeled and moved” their way through the city. Carrie Dearborn, a lesbian with disabilities, compared the event to gay pride and claimed that like at gay pride, she “could almost imagine that [she were] in the majority.” One of the event organisers, blind and bisexual Amy Hausbrook, described pride as a way for a group to “shed internalized oppression” experienced by both LGBT+ and disabled individuals.

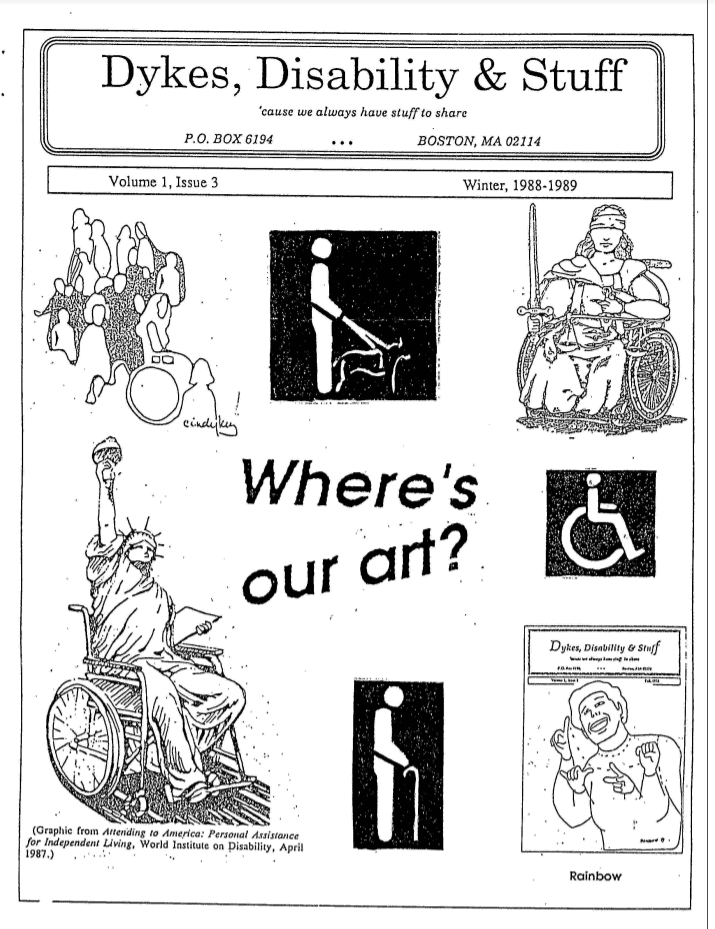

Magazines such as Dykes, Disability & Stuff (DD&S) also gave a voice to LGBT+ people with disabilities. DD&S’s intent was to provide “a communications network for disabled dykes… to help build a strong lesbian community.” It was a place for lesbians with disabilities to share their experiences, positive and negative. They focused upon empowerment, as shown by one of their cover images below, which features illustrations of powerful female figures using wheelchairs.

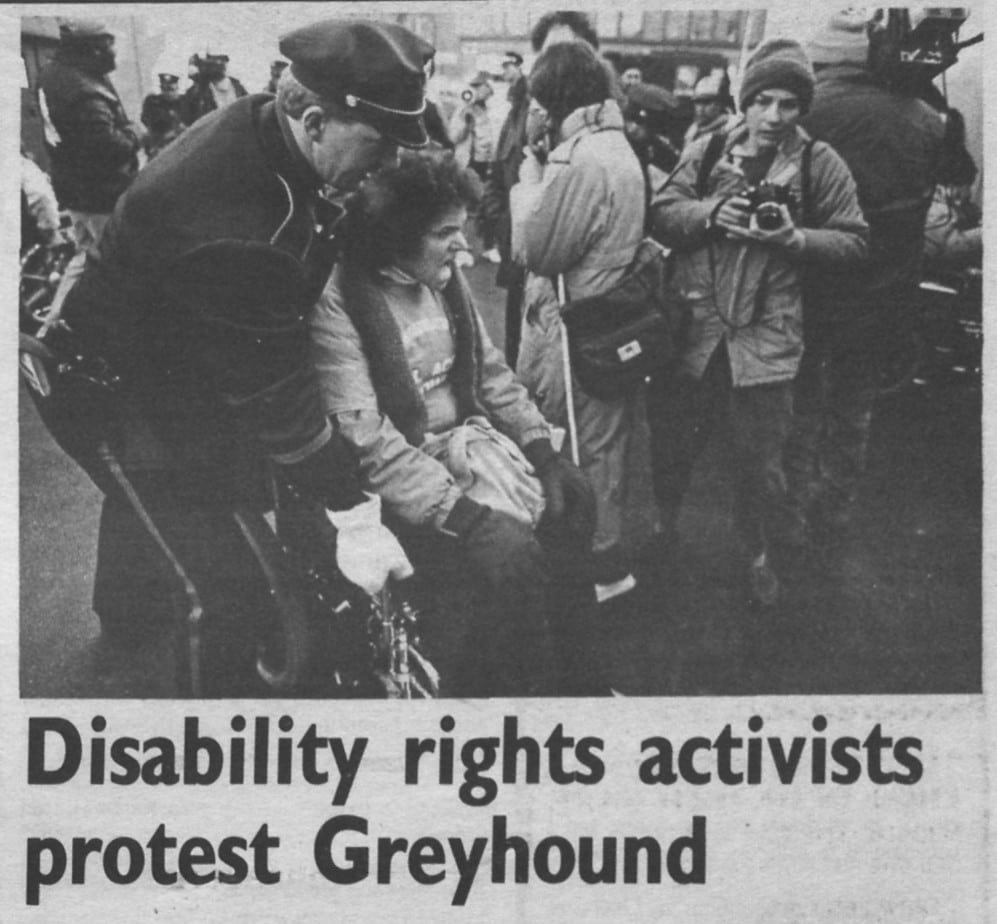

Protest

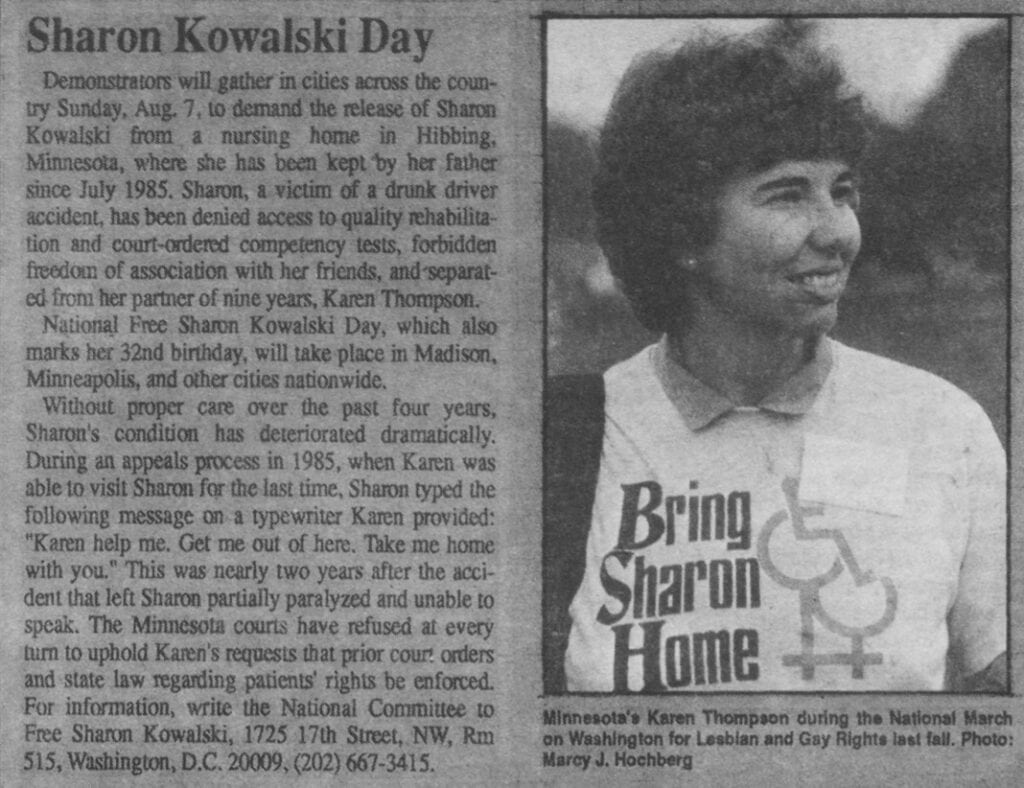

Disability pride events and magazines also provided the opportunity to protest against discrimination. DD&S encouraged its contributors and audience to speak out against non-inclusive or discriminatory venues or organisations. Boston Disability Pride included speakers from organisations including the Disabled Women’s Political Alliance and the Low-Incidence Disabilities Organising Project. They also invited Karen Thompson to speak on behalf of her disabled lover, Sharon Kowalski, whose case was frequently discussed in DD&S and other LGBT+ magazines and newspapers.

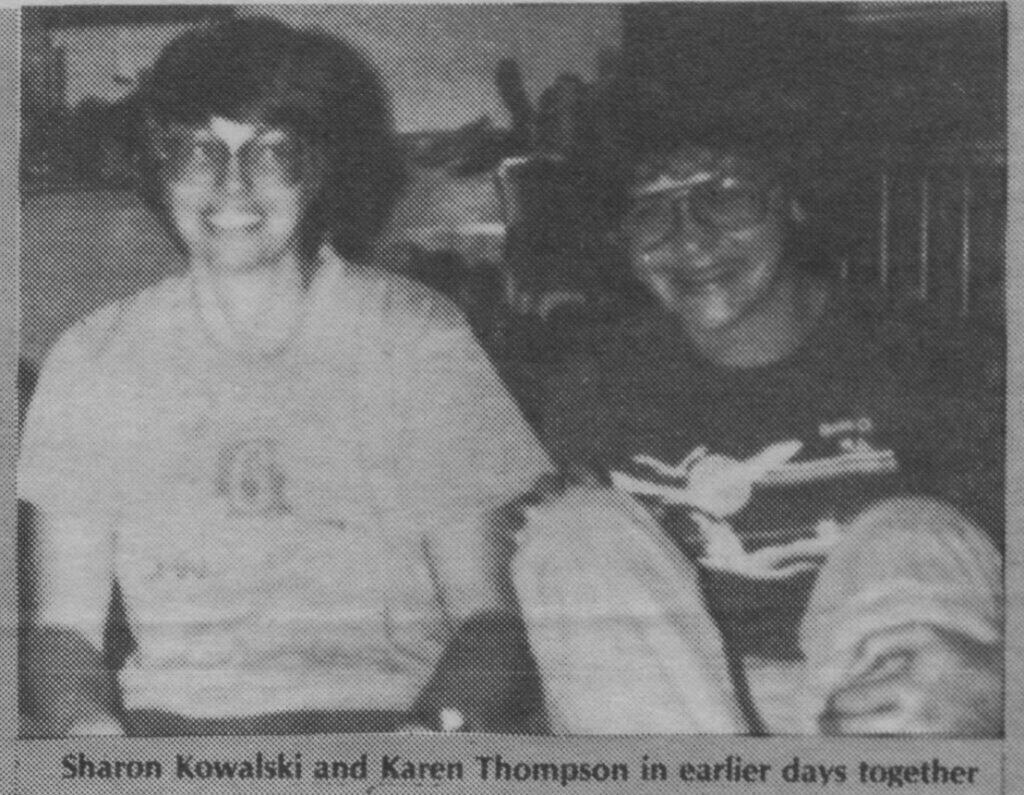

Sharon Kowalski and Karen Thompson

Sharon Kowalski was a high-school teacher from Minnesota, who lived with her long-term partner, Karen Thomson. In November 1983, Sharon was severely injured in an automobile accident. She experienced significant brain damage and extensive physical and mental disability. Both Sharon’s father Donald Kowalski and Karen sought guardianship, but Donald won. He did not accept Sharon’s relationship with Karen and in 1985, removed his daughter to a nursing home five hours from Karen. Not only was Sharon silenced – despite her brain injury, she was able to express her wish to stay with her partner – she was denied rehabilitative care.

Disability rights and gay rights activists alike protested on Karen and Sharon’s behalf, at pride events and marches, with a National Sharon Kowalski Day beginning in 1988, and in numerous articles and literature. In 1989, Karen Thompson and Dr. Julie Andrzejewski published a book titled Why Can’t Sharon Kowalski Come Home? With these efforts, a mental competency test was finally ordered, to determine whether Sharon was capable of choosing with whom she wanted to live. In 1989, Sharon was declared mentally competent enough to choose her visitors and Karen was able to visit her lover for the first time in three years. Sharon expressed her wish to live with Karen, but in 1990 Karen was once again refused guardianship. Protests continued and in December 1991, Karen finally achieved guardianship. This was a personal victory for Sharon and Karen and an important legal precedent in which the rights of a homosexual partner were recognised as equal to those of a spouse.

!["Thompson and Kowalski Address Crowd; Wins Victory." Our Own Community Press, vol. 16, no. 5, Mar. 1992, p. [1]. Archives of Sexuality and Gender](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/gale-blogpost-image-7-sharon-and-karen-post-win.jpg)

The power of activism

It’s important to acknowledge the role LGBT+ people with disabilities played in disability activism. Pride events helped give people with disabilities a voice, whether they were LGBT+ or not, and provided opportunities to protest against unfair treatment. The story of Sharon Kowalski shows that activism could be hugely successful. It also shows that being both disabled and LGBT+ comes with added discrimination and challenges. Sharon faced ableism from those who assumed a person with brain injuries could not make decisions for herself and homophobia from those who refused to acknowledge a non-heterosexual relationship. Protesting helped free Sharon Kowalski and set a precedent: the LGBT+ community would not allow their disabled members to be oppressed.

If you enjoyed reading about LGBT+ disability activism, you might like:

- The Lesbian Avengers and the Importance of Intersectionality in LGBTQ+ Activism

- The Homophobic AIDS Crisis of the 1980s

- Grassroots Activism in Amateur Publications Written by Women, African Americans and the LGBT+ Community

Blog post cover image citation: Briggs, Laura. “Disability Rights Activists Hold Historic Pride Day.” Gay Community News, vol. 18, no. 14, October 14-20, 1990, p. 3. Archives of Sexuality and Gender, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/WVJEXK526516738/AHSI?u=exeter&sid=bookmark-AHSI&xid=f925db81