│By Rebecca Chiew, Associate Editor with the Gale Asia Publishing Team│

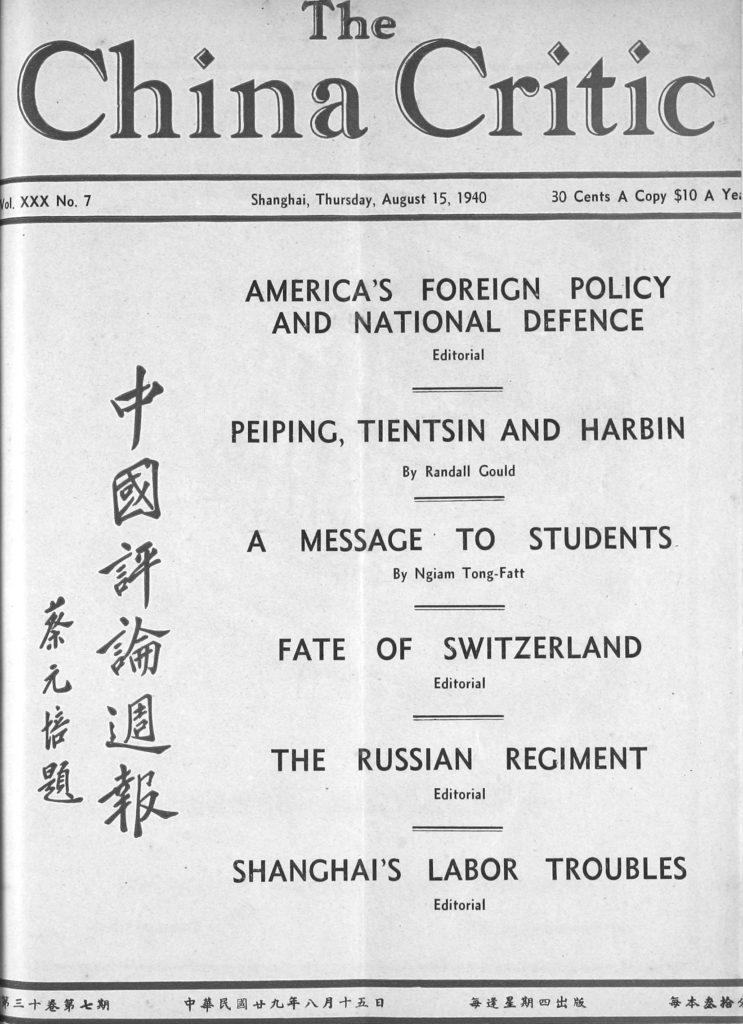

Ngiam Tong-fatt (嚴崇發 1917–?) was an overseas Chinese living in Singapore in the early and mid-twentieth century. He worked as a correspondent based in Singapore in the 1940s for The China Critic (中國評論週報, 1928–1946), a weekly periodical founded on May 31, 1928 by a group of Chinese intellectuals who had studied in the United States. Despite the editors’ avowed preference for “nonpolitical” discourse, The China Critic’s editorials and articles frequently discussed the presence of imperialism in Shanghai, debated the abolition of extraterritoriality, and advocated equal access to public facilities in the concessions. The editors also participated in wider-ranging discussions about urban affairs.

A writer fluent in English, fully conscious of his Chinese identity

How Ngiam Tong-fatt landed the job in Singapore with The China Critic is somewhat of a mystery. Although his family name “Ngiam” can be traced back to Hainan Province of China, little else is known of Ngiam Tong-fatt to this day. However, what Ngiam’s surviving essays reveal is an essayist who had an expansive mind brimming with rich ideas. Writing fluently in English, Ngiam Tong-fatt showed himself to be one who was fully conscious of his Chinese identity, drawing links between the events of the world, China, Malaya, and Singapore.

First-hand commentary, providing direct insight into events

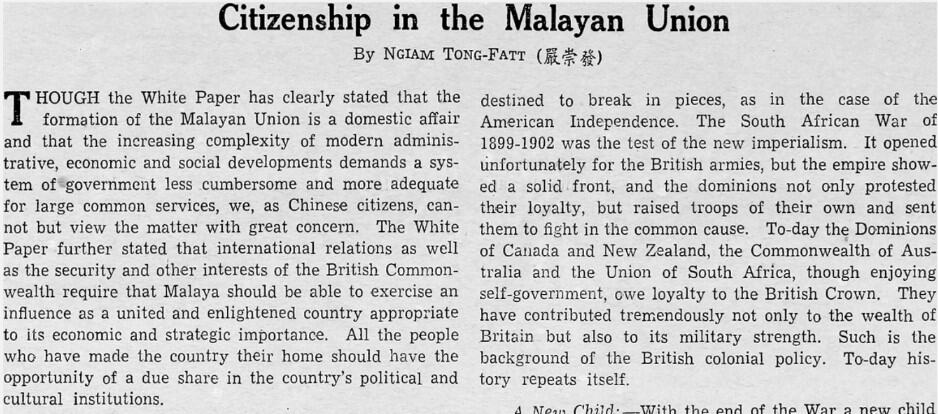

Reading Ngiam Tong-fatt’s essays transports one back in time and space. You get to hear first-hand from an excellent commentator who witnessed the surrender in Malaya of the Japanese Imperial Army and return of the British. I found issues in Ngiam’s article “Citizenship in the Malayan Union” were well-researched, and his views logically presented. It was written on May 26, 1946, nearly two months after the inauguration of the Malayan Union on April 1, 1946. In the piece, Ngiam expressed his view on and concern for the Chinese living in British Malaya.

The Malayan Union proposal, 1945

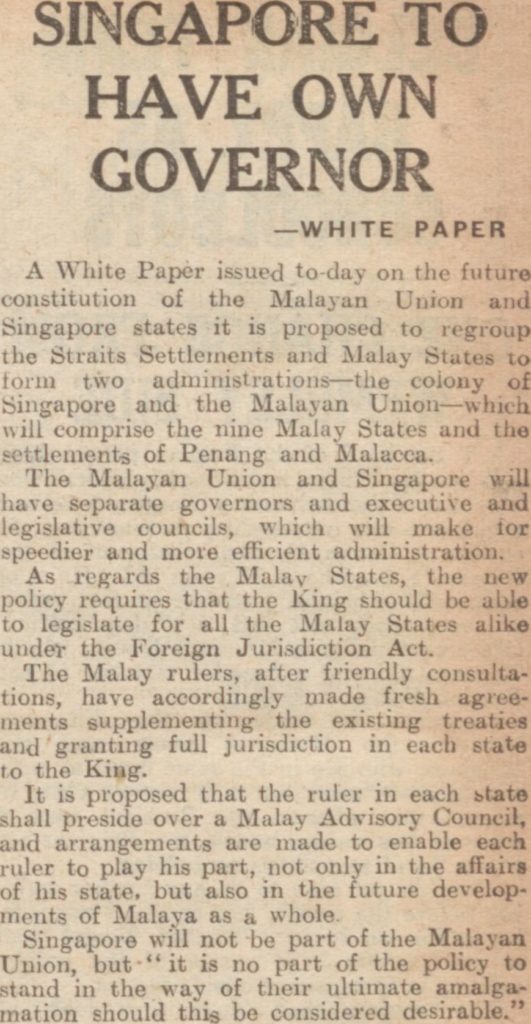

Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War and the Japanese invasion, the Malay Peninsula was under British rule. In the post-World War Two period, the UK government was planning to unify their administrative management of British Malaya (the Federated Malay States, the Unfederated Malay States, and the Straits Settlement), keeping in view eventual self-governance for the states. The Malayan Union proposal was drafted in 1945 and led by Sir Harold MacMichael; it was submitted as a white paper on January 22, 1946 and debated in the UK Parliament a week later on January 29.

The UK government debates the proposal

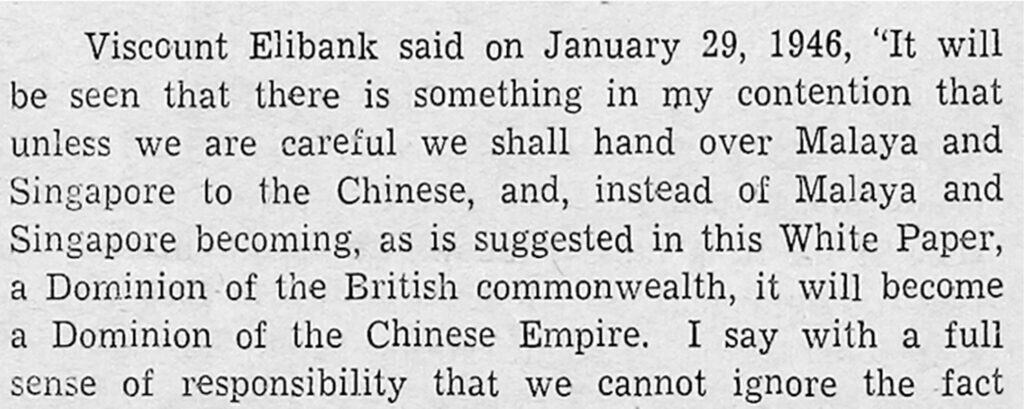

In his essay, Ngiam refers to the parliamentary debate held on January 29, 1946, in which concerns were voiced over the allegiance of and racial relations among the local Chinese population in Malaya and Singapore. In the words of Viscount Elibank:

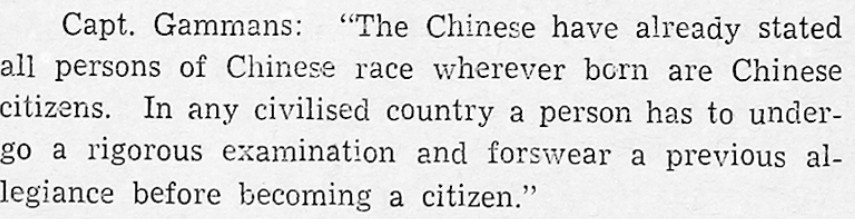

Further along, Captain L.D. Gammans said:

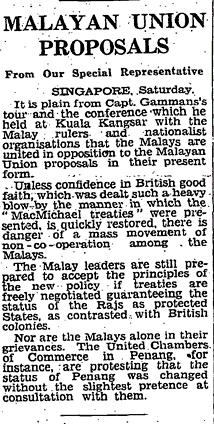

Resistance to the Malayan Union

Not only did the Malayan Union encounter resistance from the Chinese in Malaya, so too from the Sultans (or local royal rulers) of the Malay states.

Different views of Chinese citizenship

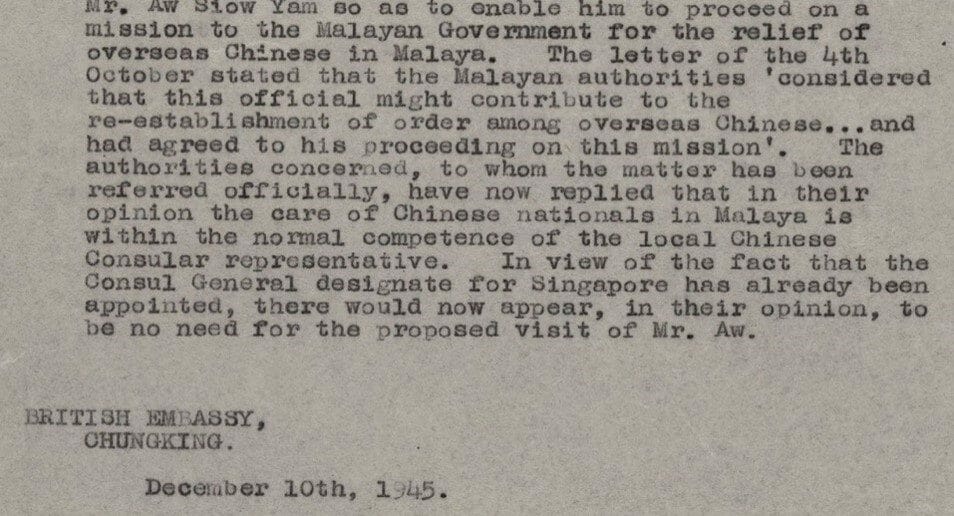

Differences between China and Britain over the treatment of Chinese citizens in Malaya had already surfaced when in October 1945 the Chinese requested for Mr. Aw Siow-yam, a Chinese businessman in Singapore, to be granted a visa to visit Malaya “for the relief of overseas Chinese in Malaya.” The British initially agreed to grant the visa, suggesting that “this official might contribute to the re-establishment of order among overseas Chinese . . . ,“ but rescinded their decision in December 1945, citing as reason “the care of Chinese nationals in Malaya is within the normal competence of the local Chinese Consular representative.”

A pertinent, insightful essay

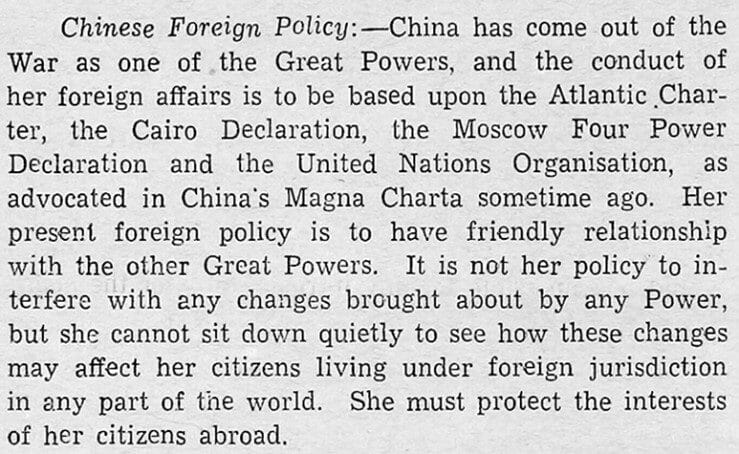

Ngiam’s essay was pertinent, recognizing that a significant moment of history was taking place in the evolution of modern international law and the process of decolonization after the Second World War. As well as addressing key arguments concerning citizenship of the Malayan Union, Ngiam made significant comments about Chinese Foreign Policy. China had emerged a victorious country and regained many of its territories that had been under Japanese control. Of Chinese foreign policy Ngiam wrote:

Different views on citizenship of the Malayan Union

Chinese citizens taking up Malayan Union citizenship would thus directly impact the status of Malaya and Singapore, an issue which is examined in E.E. Dodd’s The New Malaya: Report to the Fabian Colonial Bureau, a report available in Gale’s The Making of the Modern World archive. (The Fabian Colonial Bureau was an independent think tank that had considerable influence in the mid-1940s on British colonial policy.) How the Chinese residing in Malaya and Singapore (the Straits-born Chinese, the Chinese businessmen, the China-born English-educated Chinese, and the Chinese-educated Chinese) would respond to the British offer of citizenship of the freshly minted Malayan Union was crucial. Ngiam offered his perspective on the sentiments of these different segments of the Chinese population who made up about half of the total population (with Malays, Indians, and Eurasians making up the other half). For the Straits-born Chinese who had always considered themselves British subjects, their mind was now open to learning about their Chinese roots. For the Chinese businessman, his business interests remained paramount. For the China-born English-educated Chinese, his privileged livelihood as a government servant or an employee with a British commercial firm must continue uninterrupted. And for the Chinese-educated Chinese, the PRC Consul-General was counted on to offer him protection.

The dissolution of the Malayan Union, 1948

Moving along the history of Malaya, on February 1, 1948, two months prior to its second anniversary, the Malayan Union was dissolved, and the Federation of Malaya inaugurated. Resentment in parts of the population toward the Malayan Union continued to brew, fueling anti-colonial feelings. A prominent resistance group was the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), initially supported by the British to resist the Japanese in the Second World War, and which later became associated with the Communist Party of Malaya (or the Malayan Communist Party). Four months into the Federation of Malaya, on June 16, 1948, tensions in Malaya and Singapore erupted into guerilla warfare, leading the British to declare a state of emergency.

The great potential of Ngiam Tong-fatt’s works to researchers

Besides the controversial Malayan Union, Ngiam concerned himself with other prevailing issues of his time. Included in the Gale Primary Source collection China and the Modern World: Missionary, Sinology and Literary Periodicals (1817-1949) are eight essays, listed below, written by Ngiam for The China Critic in the years 1940–1946 (during World War Two and its immediate aftermath). In such tumultuous times, Ngiam wrote, as an overseas Chinese residing in Singapore, on the value of Chinese literature, the New Life Movement in Republican China, the achievements of Chinese civilization, and much more. For researchers and academics interested in Chinese and Southeast Asian history, Ngiam Tong-fatt is one personality waiting to be uncovered. His life and works could increase our understanding of historical, literary, social, and political trends of early and mid-twentieth century Southeast Asia.

- “Real Value of Chinese Literature,” Vol. 29, No. 6, 4 May 1940, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/XJYZOM677842218/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=80d8dcb3

- “New Life and Old China,” Vol. 29, No. 12, 20 June 1940, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/VPLGCF747200135/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=b67dc56c

- “A Message to Students,” Vol. 30, No. 7, 15 August 1940, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/PDGDQJ082718558/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=1bda0163

- “An Overseas Chinese Speaks,” Vol. 34, No. 4, 25 April 1946, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DIDNJR179468810/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=575591f6

- “Chinese Creative Power,” Vol. 34, No. 8, 23 May 1946, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/ITXMVV637697162/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=1decea72

- “Some Aspects of Chinese Civilization,” Vol. 34, No. 9, 30 May 1946, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HCFDXF715017094/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=c7e2b0b4

- “A Philosophy of Wonders in Creation,” Vol. 34, No. 10, 6 June 1946, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/NBHMKZ604439395/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=13e6320b

- “Citizenship in the Malayan Union,” Vol. 34, No. 12, 20 June 1946, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AXBOOT577666457/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=f4818770

Interested in reading more about nineteenth and twentieth century China and Southeast Asia? Try Who is the Founder of Modern Singapore?, Joseph Beech and West China Union University, Dr Wu Lien Teh as a Travelogue Writer, or The Chinese diaspora during China’s transformation from Empire to Republic.

Blog post cover image citation: Great Britain. War Office General Staff Geographical Section, and Great Britain. War Office Intelligence Branch. “Map of the Malay Peninsula, IB 289.” British Library: Ministry of Defense Maps, Primary Source Media, 1883. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CGQVOQ676034950/NCCO?u=asiademo&sid=NCCO&xid=e31596f0.