| By Constance Lam, Gale Ambassador at the University of Durham |

No matter the situation, and no matter the company, it is an unspoken rule in the UK that a cup of tea (and likely several more cups) will always be poured and sipped! Despite the ubiquity of tea-drinking, I would argue the consumer base of tearooms and cafés is distinctly female-dominated. This begs the question: why is the act of drinking tea so closely associated with women when it is in reality a universal habit in the UK? I’m also curious to explore how tearooms and tea-drinking featured in one of the most significant women’s rights movements in the UK to date – the fight for women’s suffrage.

“Part of our success lies in food and friendship”

To quench my curiosity, I first brewed myself a cup of earl grey tea, and then started browsing Gale’s primary sources online, initially focusing on the archive British Library Newspapers. After entering the search terms “tea” and “women”, I was brought to an Evening Telegraph article titled “Suffragettes and Tea Parties”. Written in 1908, the article highlights the role of tearooms in the suffragettes’ campaign, explaining that “drawing-room teas and meetings take place constantly in many of the large West End houses, where the gospel of women’s votes is preached.” In another article from the same archive but this time in The Dundee Courier, Miss Patricia Hall, a young suffragette speaker, is reported as declaring, “I am convinced that part of our success lies in food and friendship.” The article goes on to say, “Three women magistrates who were present, agreed that the promise of a cup of tea was a great inducement to get women to come to meetings and discuss problems which would otherwise not be dealt with.”

A space to express themselves

Furthermore, I would argue that, unlike public spaces such as restaurants which in the first few decades of the twentieth century were male-dominated and seemingly more hostile, in tearooms women were able to freely express themselves with like-minded peers without feeling silenced or censored. Indeed, the tearooms were not simply a place of peaceful discussion: there, suffragettes were able to voice their political dissent and protest.

It is perhaps this energy and confidence, gained from animated discussions in tearooms that led to bolder suffragette activity. A Western Times article published in 1908 reports an incident where a leading suffragette, Mrs. Drummond, stood on the roof of a small steam boat which had steamed down the Thames, stopping outside the Terrace of the Houses of Parliament where a “few ladies had at that hour assembled on the terrace for afternoon tea”. Drummond used the opportunity for the suffrage campaign, declaring, “as women were not allowed in the House of Commons, and were turned out of public meetings when they advocated their cause, they took that opportunity of demonstrating on the river, in front of the Parliamentary terrace.” She also added “she had gone to gaol [jail] for her principles, which was more than Members of Parliament had done.”

Kew Gardens tea pavilion burnt down

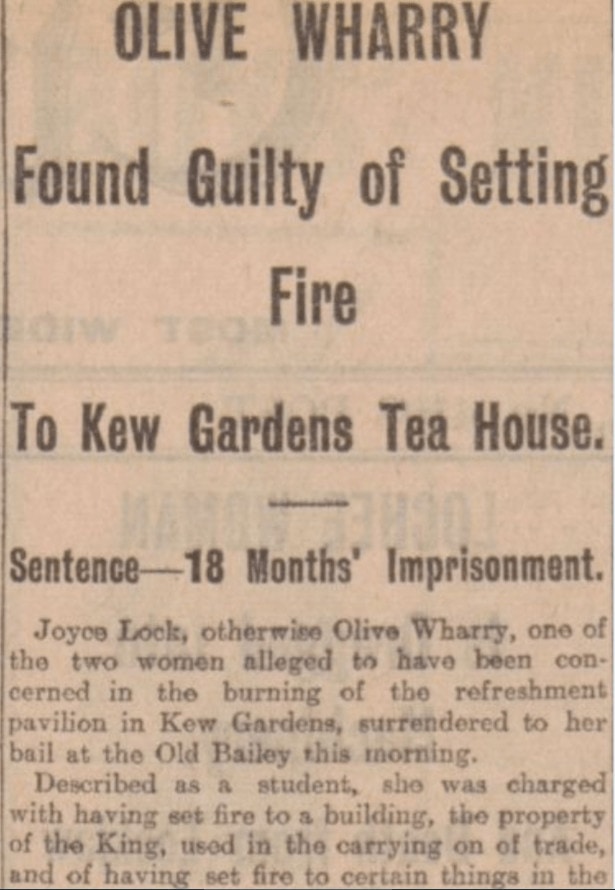

Due to the government’s lack of response to the suffragettes’ demands, they resorted to increasingly radical tactics, including arson, and interestingly the location chosen for one such incident was again linked to tea-drinking. In February 1913, the student suffragette Olive Wharry burned down the Kew Gardens tea pavilion. This article by the Evening Telegraph describes Wharry as a “prepossessing young woman” who “was seen to throw away a small electric lamp” during the incident. Over six decades after the Kew Gardens fire, Wharry’s legacy is commemorated in an article in The Independent as “Wharry’s most serious offence in a career of anarchy that earned her at least six prison sentences between 1911 and 1914, and resulted in the longest hunger strike in suffragette history.”

“Suffragette Protest Ends With A Cup of Tea”

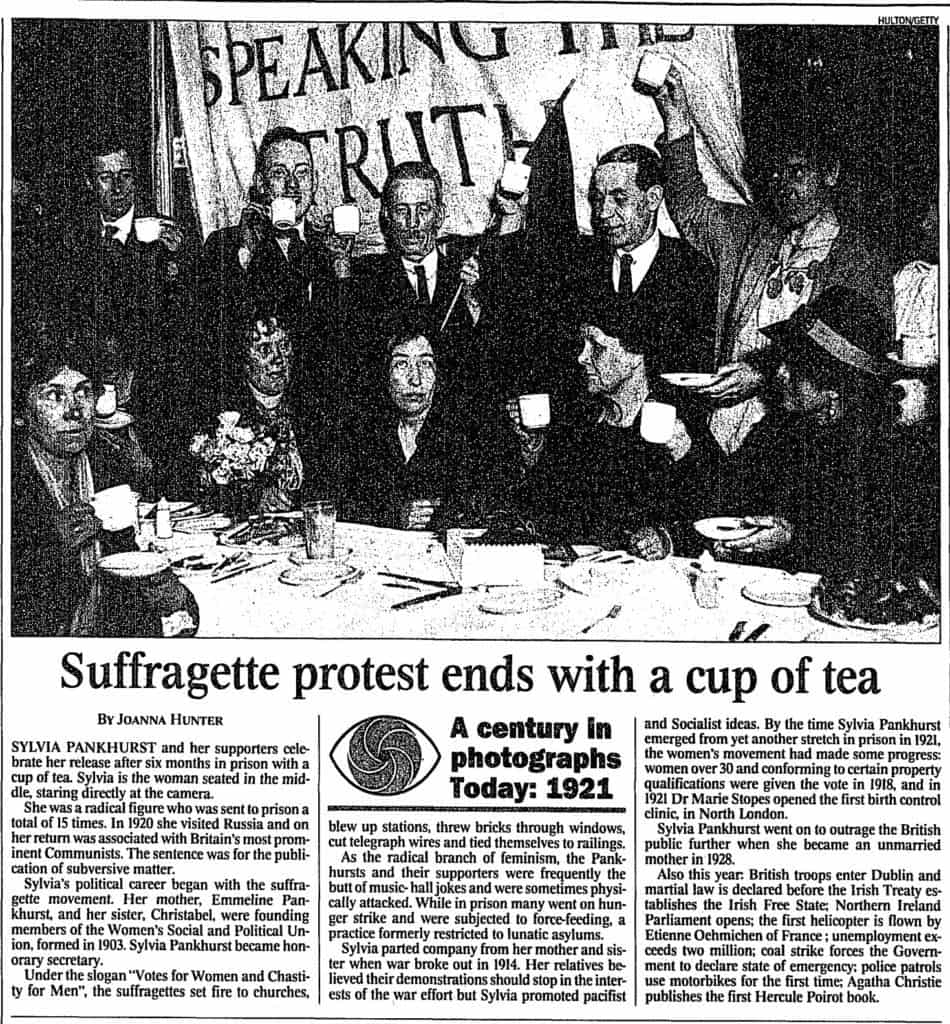

Beyond the British Library Newspapers archive, I discovered a wealth of material in Gale’s primary sources online focusing on key figures in the suffragette movement, especially Sylvia Pankhurst, daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst. Joanna Hunter’s 1999 article in The Times Digital Archive, “Suffragette Protest Ends With A Cup of Tea” reminds us that Sylvia “was a radical figure who was sent to Prison a total of 15 times”, and outlines the activities of the suffragettes, who “set fire to churches, blew up slogans, threw bricks through windows, cut telegraph wires, and tied themselves to railings.” The photograph in the article (below) depicts Pankhurst and her supporters celebrating her release from prison. Sylvia is seated in the middle staring directly at the camera, emphasising her total dedication to the cause, and creating a general sense of seriousness and urgency that is perhaps in contradiction to the idea of relaxing with a celebratory cup of tea.

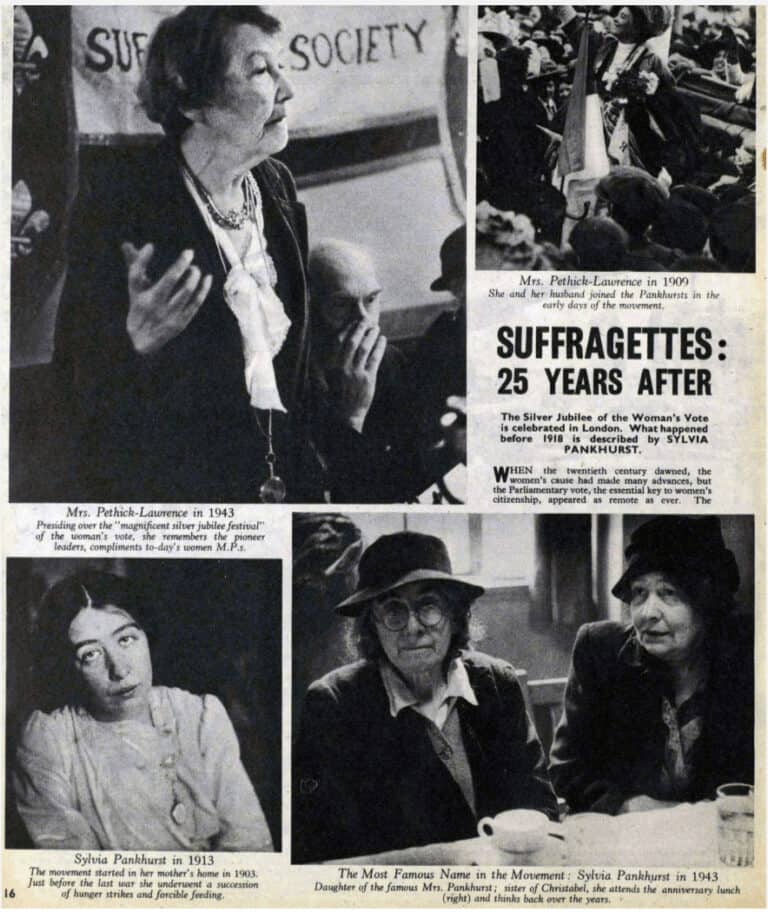

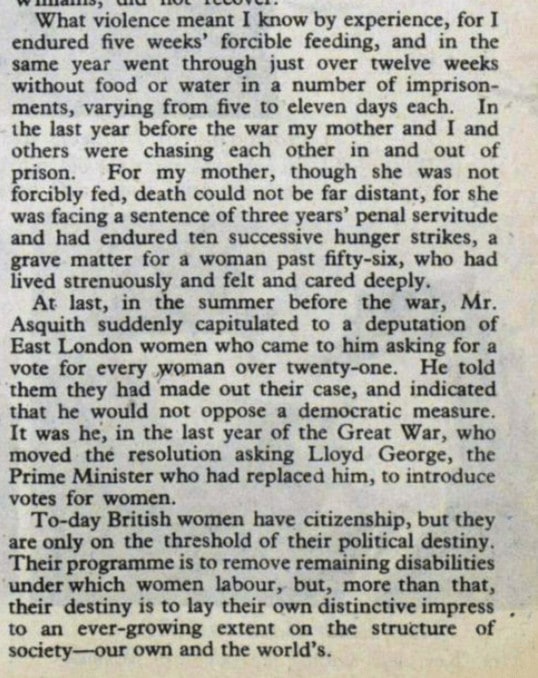

Likewise, the 1943 feature “Suffragettes: 25 Years after” from the Picture Post Historical Archive focuses on the legacy of Sylvia Pankhurst, publishing her account of the suffrage movement and her period of imprisonment.

“Suffragettes: 25 Years after.” Picture Post, 20 Feb. 1943, p. 16+. Picture Post Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EL1800014998/GDCS?u=duruni&sid=GDCS&xid=5c55acb4

“Suffragettes: 25 Years after.” Picture Post, 20 Feb. 1943, p. 16+. Picture Post Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EL1800014998/GDCS?u=duruni&sid=GDCS&xid=5c55acb4

Pankhurst ends her article (above) by reminding British women that they are “only on the threshold of their political destiny.” Indeed, over 100 years later, we must not forget the suffragettes’ legacy, which started in the tea-rooms, and create similarly empowering spaces of debate and discussion in the twenty-first century.