│ By Kyle Sheldrake, Marketing Manager – Insights and Development│

As we approach fifty years since man first set foot on the moon, it feels like a good time to reflect on attitudes and opinions in the lead up to one of humanity’s greatest scientific achievements. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to think that the space race was always seen positively, receiving unanimous public support and the unity of the scientific community, but this was not necessarily the case.

Below is an extract from Part II of a case study recently added to our website which explores a question hotly debated in the 1950s and ’60s: was it worth it? Public and scientific opinion went back and forth between cynicism and optimism in the decade before man landed on the moon, with many questions asked about the true motivations (was it a serious scientific endeavour or a display of national power?) and the various costs (will the result be worth the money spent, and the potential human cost?)

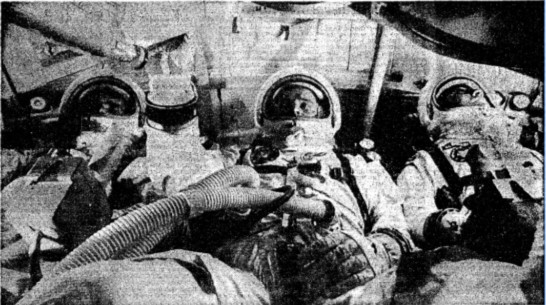

![“The Apollo astronauts getting…familiar with the capsule that will take them to the suburbs of the moon next month…from left: Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin Aldrin.” "Astronauts to Plant U.S. Flag on the Moon." International Herald Tribune [European Edition], 12 June 1969, p. [1]+. International Herald Tribune Historical Archive 1887-2013,](https://www.gale.com/intl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/image-1-1.jpg)

Was the space race worth it?

Despite the eventual success, there had been a lot of negative coverage. Commentators argued that the outcome of the space race was not just a display of technological dominance, but a symbol of world politics: an American failure to win the space race would signal the victory of the Communist regime over Western freedom, and of dictatorship over democracy. Away from the grand political metaphors, more immediate concerns were also gathering momentum. A correspondent from The Times reported from Washington on the “revulsion” toward the idea of the space race, underpinned by “the belief that the prestige attached to putting a man on the moon is not worth the enormous cost or the celestial casualties which will be the second price to be paid for the dangerous haste”.

The concern over the financial and potential human cost of attempting a manned moon landing through a rushed programme became a central point for questioning the need for the space race at all. The debate prompted another important question: did space exploration need to be manned? After the Soviet Union ‘leaked’ to him that they were having doubts about the manned moon race, Sir Bernard Lovell attempted to convince the “President that the Russians, like some American scientists, think that just as much can be discovered more quickly and cheaply by unmanned probes”. Plus there was a growing feeling that the race was not truly motivated by discovery but that “nationalism has triumphed so far”. Scientists and politicians were increasingly against a programme that had become more about political philosophies than science.

!["Astronauts to Plant U.S. Flag on the Moon." International Herald Tribune [European Edition], 12 June 1969, p. [1]+. International Herald Tribune Historical Archive 1887-2013](https://www.gale.com/intl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/image-3-1.jpg)

https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CS168518793/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=f3544fb9

A report in The Telegraph highlighted the dominance of the moon landing project, and the economic difficulties it caused for other scientific endeavours, with some stark numbers: by the end of 1964 the moon project would have cost the US £3,000 million, whilst cancer research would have only had £50 million that year; by 1963, America was spending £5 million a day on the moon project.

To find out more about the Space Race as depicted throughout Gale Primary Sources, you can read the full three-part case study The Space Race to put a Man on the Moon: Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the Moon Landing in the new Archives Explored section of our website.

Blog post cover image citation: “The astronauts practising in an Apollo capsule, identical to the one in which they died. From left: Chaffee, White, Grissom.” “Death . . .” Sunday Times, 29 Jan. 1967, p. 11. The Sunday Times Digital Archive, https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/FP1800702733/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=5b483ed9