│By Lyndsey England, Gale Ambassador at Durham University │

‘What should we suppose must naturally be the consequence of our carrying on a Slave Trade with Africa?’ asked William Wilberforce in a speech in 1789. ‘Does anyone suppose a Slave Trade would help their civilization? That Africa would profit from such an intercourse? Is it not plain, that she must suffer from it?’ With these questions in mind, the famed abolitionist made a decisive judgement: ‘We are all guilty,’ he said, ‘we ought all to plead guilty’.

This speech, on the question of the abolition of the slave trade, is just one example of Wilberforce’s exceptional skills as an orator that can be found within Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Equipped with this powerful rhetoric, Wilberforce memorably established his humanitarian position in the political sphere, actively campaigning against the injustices of the slave system for most of his life. Indeed, William Wilberforce is popularly believed to have been instrumental in leading Britain’s move towards the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, and is frequently celebrated on account of this fact.

For instance, in 1933, The Times noted how the West Indies cricket team offered a show of support to Lord Irwin, chairman of the William Wilberforce Memorial Appeal Committee:

Many would still agree with the assertion that Wilberforce ‘bowled out slavery’. In fact, evidence of this interpretation of abolition can be seen frequently, and is particularly evident in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, which romantically portrays Wilberforce as a paragon of virtue, battling against parliament’s inhumane commitment to the Slave Trade. However, despite Wilberforce’s admirable efforts, historians have not always expressed a consensus as to the prominent role of the abolitionists in overturning the transatlantic slave system.

For instance, in his 1944 book Capitalism and Slavery, West Indian historian Eric Williams noted that the role of the abolitionists has been ‘seriously misunderstood and grossly exaggerated’. 1 Commending the abolitionists for being the ‘spearhead of the onslaught which destroyed the West Indian system’, Williams nevertheless claimed that the British abolitionist movement was not a triumph of humanitarian principles but instead simply ‘one of the greatest propaganda movements of all time’. In Williams’ view, the real impulse behind abolition and, eventually, emancipation, was the economic demands of the Industrial Revolution. In Britain’s rapidly industrialising economy, the Slave Trade ceased to function as a viable source of capital.

While Williams’ view has been critiqued for undervaluing the humanitarian accomplishments of the abolitionists, there is still something to be said in favour of the statement that the abolitionists made a considerable contribution to the development of modern propaganda campaigns.

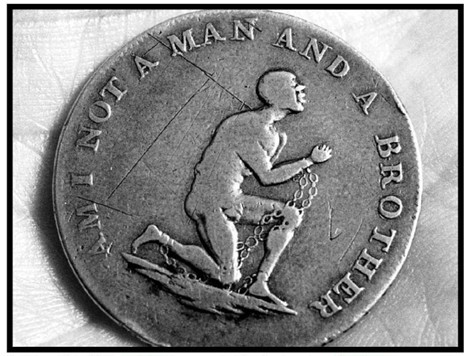

In line with the establishment of the Society of the Abolition of the Slave Trade, famed potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood designed the haunting image of a supplicant slave kneeling beneath the question ‘Am I not A Man and A Brother?’. The image was to become the emblem of the Society, and was thus arguably the first ‘logo’ created in order to further a political cause. It was later adapted and used on medallions and other objects, both in Britain and in the Americas, an example of which was pictured in an article in The Independent in 2005:

Based on this alone, it is clear that the abolitionists had an innovative approach to their campaigning strategy. In the midst of the rising consumerist tendencies of Britain’s newly industrialising population in the late eighteenth century, the Society utilised Wedgwood’s success and skills as a pottery manufacturer to expand their influence and garner more attention for their cause.

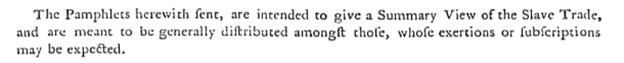

Of course, their propaganda efforts went beyond this single example. Take for instance the following 1787 document which describes the campaigning efforts of the Society of the Abolition of the Slave Trade:

http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CW0107384721/GDCS?u=duruni&sid=GDCS&xid=106960f3

The document serves as a cover letter for pamphlets which were to be circulated amongst the British population, appealing to their conscience and sense of moral obligation.

Along with the depraved inhumanity of the Slave Trade, it is necessary to acknowledge the concerted, pioneering efforts that men such as Wilberforce, Wedgwood and John Newton undertook to challenge the prevailing views of their society. Even in light of The Williams Thesis discussed above, the actions of the abolitionists retain their poignancy. Indeed, perhaps the abolitionist movement was ‘one of the greatest propaganda movements of all time’ because, at its core, it represented the unabashed hope for a triumph of humanitarian values.

It may seem to be an idealistic approach, but as Roz Kaveney put it in his article in The Independent:

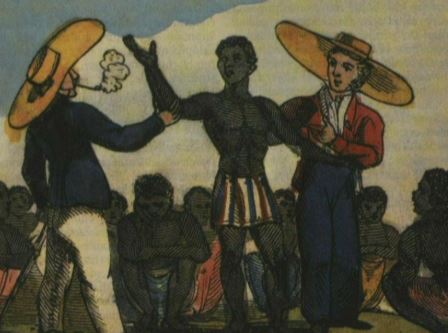

Blog post cover image citation: “Black and white-and red all over.” Economist, 27 Aug. 2005, p. 74. The Economist Historical Archive, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/GP4100354941/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=3e0df10b