│By André Buller, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth │

Ideas of sorcery, witchcraft and incantations have persisted in intriguing me throughout my years of study. The ways in which the supernatural arose and manifested alongside historical events has always fascinated me, and consequently I’ve found myself studying subjects that considered the mystical in both the literary and historical units of my degree. The topics I’ve studied in these classes have ranged as widely as manifestations of the supernatural have in the past. One week I’d study the seventeenth century, witch-hunts of Salem and the pursuits of Matthew Hopkins, but by the next week be focusing on the rise of Occultism.

Though definitely interesting, the famous contention between sceptical magician Harry Houdini and stalwart believer Arthur Conan Doyle did not discuss specific methods of magical practise at that time, leaving something of a gap in my knowledge of how the mysticality of witchcraft persisted in the nineteenth century. However, Gale Primary Sources proved bountiful once again, and through exploring this wealth of documents it is possible to answer methodological questions – such as how people cast spells – to those of a more analytical nature, such as how witchcraft was defined in the Victorian era.

Bodily Magic

A notable distinction I found in the sources were those that discussed witchcraft in relation to the body, either inflicted upon or released from it. The Morning Chronicle of 1828, one of the periodicals in Gale’s British Library Newspapers collection, describes the actions of one Rose Pares, who “enjoyed the reputation of being a witch,” as she treated an ill peasant girl. Marching into the room, Rose was swift to diagnose the child as “bewitched” before ordering those present to help her arrange the room for her magic. The writing is useful in showing contemporarily agreed constants of witchcraft; “Little as we are initiated into the secrets of magic, we know that odd numbers, and especially the number three, have singular virtues; therefore, three, multiplied by three, must be a number prodigiously powerful.” For this reason, the witch used nine heated stones to make a mystical vapour, before using coins to extract the spiritual malevolence from the girl’s body.

!["CASE OF WITCHCRAFT." Morning Chronicle [1801], 28 Sept. 1829. British Library Newspapers,](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GALE_IMAGE_2.png)

Similarly, in 1848, the Boston Investigator, a periodical in Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, provides more magical constants that witchcraft ascribed to the body. It describes the energies that emit from the body, as a form called “effluvia,” and determines that the eye, an imperative tool in the craft of sorcery, manipulates and slings this energy in order to cast spells. In these ways, methods of witchcraft persisted through relation to physical needs and attributes, either in illness or in physiology.

Occult ideas

In addition to physicality, witchcraft methodology often found itself inexorably linked to idiosyncratic ideas of occultism. For example, Gale’s Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers archive includes an article from 1851 that described supernatural communication in occultist terms, linking interactions with “spirits” to certain sounds and knocks. Individuals would “establish confidence” in a “guardian spirit”, using pencils and sounds to inquire questions toward the supernatural entity from beyond the grave. Indeed, nineteenth century preternatural methodology built upon a mixture of such occultist and traditional ‘witchy’ concepts.

In the Portland Oregonian in 1892 an article discussed hypnotism and puppetry: “It will be remembered that the genuine “witches” of the Puritan era had, or were alleged to have had, a tantalizing habit of maltreating their victims by making little dolls or “poppets,” as they were called, giving them the names of the persons whom they wished to persecute, and then sticking pins in them”. Though aged by the time of authorship, such methods had persisted – albeit evolving over time. The column describes how a Dr. Luys “claimed to have succeeded in transferring the sensibilities of a hypnotized person to an inanimate object”. Apparently, he managed to place a woman’s mind into a glass of water, who winced when the water was touched or drank. Thus, it becomes clear that these supernatural methods and views survived the century, though evolved to mirror the trends of the times.

!["Modern 'Witchcraft'." Portland Oregonian [Oregon Territory], 22 Dec. 1892, p. 4. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers,](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/gale_image_5.png)

Undeniable humanity

Though supernatural methods shifted in mysticism, in some ways witchcraft remained a distinctly human affair. Recorded in the British Library Newspapers archive is the violence of Annie Gilroy, who was charged with assaulting Jane Forden in 1874. According to Anne, she acted out of defence; “The defendant fancied that she was “bewitched” by the complainant, and determined to “draw blood” as the approved method of dispelling the witchcraft. This she succeeded in doing by committing the assault.” Though there is no real supernatural discussion, Anne felt she could make the case for her actions with witchcraft, giving credence to the idea that it was, at least to some extent, still a believed phenomenon with rules and exceptions to subvert.

It is difficult to determine any set definitions to the particular methods of spellcasting in the nineteenth century, but it certainly is possible to determine the perpetuation of the supernatural. Witchcraft continued to evolve and manifest as a concept; though the cauldron and the frog may have vanished, the influence, belief and practise remained. Through Gale’s archives we may round about the sources go – and still the witchcraft practise know![1]

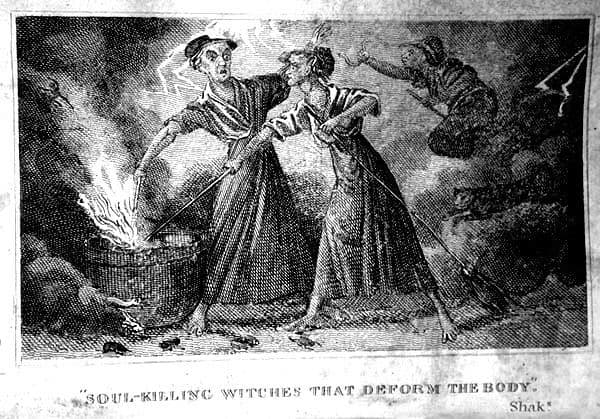

Blog post cover image citation:Soul-Killing Witches that Deform the Body by Robert Calef, 1828 [Public domain] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Calef_witches_1828.jpg

[1] For those keen to put their finger on the quote I allude to… it’s Macbeth, Act IV, Scene I: “Round about the cauldron go; In the poison’d entrails throw.”