By Grace Mitchell-Kilpatrick, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter

The issue of climate change is often one which is put on the backburner by both politicians and the population at large. Whilst the issue has been on the political agenda in several countries numerous times in the twenty-first century, the efforts to bring about impactful change remain minimal. I thought it would be interesting to use Gale Primary Sources to investigate the developing history of climate change consensus over the last thirty years or so.

As late as 1990, there was still a general consensus of uncertainty regarding the reality of climate change, highlighted in an article in The Times Digital Archive; the ‘unknown’ future of the environment lulled the public into a false sense of security. Scholars, however, warned that global warming would lead to increased sea temperatures in the near future.

After filtering my results in Gale Primary Sources by year, I found a shift in consensus as we neared the end of the twentieth century. This article from 1999 provides us with a snapshot of the way attitudes towards climate change had begun to change over the last decade or so. Environmental concern had started to spread from academics to global governments, exemplified by the emergence of the UN Framework on Climate Change, an agreement signed in 1992 by 155 countries to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

In the years since then, there has been a lot more literature published warning about climate change, as well as newspaper features. Using the Term Cluster tool in Gale Primary Sources I discovered the article ‘Why a sustainable future really matters’. It offers a convincing argument for the rationale that we should attribute more importance to the issue of the environment, proportionate with the significant scale of the issue.

According to the majority of scholars (bar the climate change deniers) the ‘tragedy of the commons’ theory can explain the environmental issue we face. Hardin’s ‘tragedy of the commons’ posits that people use land without any duty to maintain, due to self-interest. Therefore, though one day the demand will exceed supply, no one currently has any incentive to maintain the public good of the land. As a result, global warming will continue to accelerate due to high consumption of plastics, fuels and electricity, meaning a degradation of our oceans, natural resources and wildlife habitats. Such treatment of the environment is unsustainable.

I did some cross-searching in Gale’s archives and found that there is no denying that progress has been made in the environmental arena, but there is still a long way to go – these changes only contribute to a small improvement on the forecasted global warming. Plus, on an international level, powerful and influential countries such as America and China refuse to cooperate due to vested political and business interests; politicians continue to make the environment a low-level agenda priority, using security-focused rhetoric instead. On an individual level, the lack of accountability continues – consumers see little benefit of making personal changes such as recycling.

A sustainable future is imperative in order to avoid a ‘tragedy of the commons’. Straws and bags only contribute to a small proportion of environmental damage. Rather, as the article on sustainable futures I mentioned earlier states, multi-national companies should be offered appealing incentives in order to conduct their service and goods delivery in the most sustainable way. Tackling product and food waste, as well as energy emissions would be beneficial – perhaps via taxation, or initiatives to produce less waste in the beginning. There is an individual and collective responsibility to reduce consumption and waste to enable a more sustainable future. As Giddens recognises, there is a need to adopt a ‘language of opportunities’ to instil positive changes.

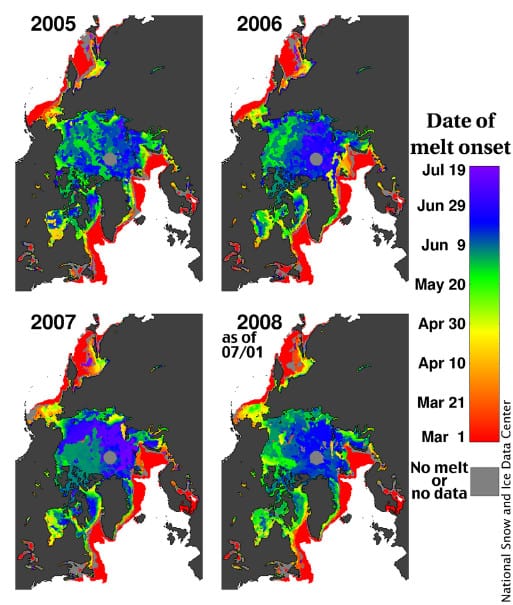

Blog post cover image citation: Wikicommons: National Snow and Ice Data Center (2008) Date of first melt of Arctic Sea ice.png, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Date_of_first_melt_of_Arctic_Sea_ice.png (Accessed: 4th October 2018) from http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/index.html