Sir Ernest Mason Satow, British diplomat and renowned Japanologist, was a lynchpin of Anglo-Chinese and Anglo-Japanese relations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. During his long diplomatic career, Satow wrote many books on the region, including several on Japan during the transition from rule by the Tokugawa shogunate back to imperial power in the Meiji Restoration of 1868. His papers are an invaluable and unique resource on the British in Asia and on East Asian diplomacy at a fascinating time, through the private papers, diplomatic correspondence and personal diaries of a man at the centre of international events.

Below, Miyazawa Shinichi, visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of International Sinological Studies, Beijing Language and Culture University, discusses some of Ernest Satow’s life and legacy.

Ernest Mason Satow: An Essay

Miyazawa Shinichi

In May 1861, Ernest Mason Satow (1843–1929) was wondering what to do after getting a B.A. at University College London. One option was to continue studying at Cambridge University. Another option, though a vague one, was to follow his elder brother, Edward Mason Satow (1840–1865), [1] to the Far East. Edward, who had received early training in business under their father, had many more traits in common with the younger Satow, for he had the makings of a scholar and a multi-linguist, with knowledge of German, Spanish, Russian, Malay, and Chinese. Ultimately, Edward went to Singapore and then moved to Shanghai, where he died of cholera at 25.

It was Edward, shortly before his departure for Singapore, who brought home one of Laurence Oliphant’s interesting books, [2] which he borrowed from the Mudie’s Lending Library. Oliphant lured and engrossed the young Satow with exotic scenes of “some dreamland”, so much so that he decided to sit the exams for the selection of student interpreterships in China and Japan. On August 20, he received his nomination from the Foreign Office. Satow’s choice was for Japan, on the strength of Oliphant’s charming words: “…well might we imagine ourselves gliding across these solitary waters to some dreamland, securely set in a quiet corner of another world, far away from the storms and troubles of this one.” [3]

Laurence Oliphant (1829–1888) was a strange man with a journalist’s premonition for approaching critical moments, and a travelogue writer’s keen sense of observation. He was self-conscious of his character and adventurous lifestyle when he gave the subtitle Moss from a Rolling Stone [4] to his autobiography. Oliphant was a rolling stone abroad, gathering not the green living moss but the figurative “moss” of experiences and observations right on the spot of critical situations in history. It was an education by contact at the height of Victorian expansionism. Oliphant and Satow were quite different in character and lifestyle, but when young and fresh in Shanghai, Peking, Edo, and Yokohama, Satow started his consular service as a rolling stone à la Oliphant.

Satow wrote in his diary from Shanghai, 5 February 1862, about his mixing with a circle of British merchant adventurers: “Afterwards, I played Billiards with Veitchat at Michie’s, [5] & saw Dallas, Turner, Gordon, King & Smith.” These were also friends of Charles Lenox Richardson, especially Barnes Dallas [6] who had travelled in company with Richardson from England to China on board the Indus, reaching Hong Kong on 11 March 1853, and departing for Shanghai with Robert Fortune added to their company. Satow arrived at Yokohama on 8 September 1862, and scarcely one week had passed, when on Sunday 14, Richardson, enjoying a summer vacation in Yokohama, was murdered by the Satsuma clan’s retainer on the main public road, called Tōkaido. This early episode in Shanghai and Yokohama in connection with Richardson and his friends shows us an example of education by contact on the part of the young Satow.

There is another episode to tell about moss, especially about the old saying, “A rolling stone gathers no moss”. About twenty years ago, in quest of some Richardson relics, I paid a research trip to Leamington Spa and Tunbridge Wells. In the graveyard of the Culverton Parish Church, I succeeded in locating the tombstone of Louisa, Richardson’s mother, under one of the huge oak trees. It was very easy to read its old inscriptions, for they stood out clear and fresh, as if raised, on the slab face. Perhaps, some readers may remember that one of the temporary residents at Leamington Spa was Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote in his essay “Leamington Spa” [7] that “beautifully embossed in raised letters of living green, a bas-relief of velvet moss on the marble slab.”

The young Satow had certainly spent a period of his life as a rolling stone. His natural character as a diligent scholar, patient linguist, and faithful diplomatic negotiator gradually asserted itself inward and outward. Meyrick Hewlett was a witness. Hewlett was first picked up as private secretary by British Minister Claude Macdonald at the critical moment of the Legation Siege in Peking in the summer of 1900. Hewlett was then attached in the same capacity to Satow, and bore witness to his new Minister’s being “an austere man”. Satow was not only “hard on his staff”, [8] but also hard and just in negotiating over the Protocol with Li Hung-chang, a prominent Chinese politician and diplomat. We find Satow no more like a rolling stone, but rather like a secure stone under an oak tree.

Jennie, widow of George Ernest Morrison, [9] addressed a letter of thanks, dated June 1920, to Satow, who was then enjoying his pleasant and settled life after retirement in “Beaumont” at Ottery St. Mary. She said that “I was very touched and grateful to you for coming over yesterday. My dear Man had such an unbounded admiration and affection to you, and it was a great joy to him to see you in your beautiful home.” [10] Jennie and Morrison had made this visit in return to Satow’s earlier call, before Morrison’s death in May 1920. Morrison referred to their return visit as well as Satow’s call in his diary. [11] They had much to talk about: one interesting subject was mutual friends of their Peking days, including Valentine Chirol [12] and Edmund Backhouse. [13] Chirol was remembered fondly by them both, for he was a frequent visitor to “Beaumont” and Morrison’s former colleague at the Times. Satow also wanted to hear Morrison’s view of Backhouse, another book-hunter though suspected of forgery, and their secretive informant in Peking.

Morrison also recorded his visit to “Beaumont” in a letter, [14] summing up his admiration for the scholarly gentleman’s way of life: a large house, library, and beautiful gardens. Satow had cherry blossom and pear trees planted, many of which he bought at the Veitch’s nurseries, besides colourful Japanese maple trees raised from the seeds Masujima [増島六一郎] sent him from Tokyo. In this connection, many readers may like to remember the avenue of beautiful cherry trees that Satow took so much trouble to plant and grow near the British Embassy in Tokyo [千鳥ヶ淵櫻並木]. [15]

Satow was a plant-hunter, whose botanical enthusiasm eventually permeated into the heart of his son, Hisakichi [武田久吉]. Satow invited him to come to England, and supported his studies at Kew Gardens by giving him an annual allowance of £200, the same sum the young Satow used to be paid by his Government.

Satow was a lifelong collector of books and an avid reader. He built a large collection of books written in many different languages. On one occasion, he spent two days counting the number of books in his library. [16] A special collection occupied a bookcase of its own: the Dante collection, including the complete Japanese works by Nakayama [中山昌樹]. Satow compared the Japanese Dante scholar’s translations with their original counterparts, and reported to Paget Jackson Toynbee, a renowned UK Dante scholar. Another bookcase held Satow’s rare collection of Erasmus. His nephew, Percy Stafford Allen, was an Erasmus scholar at Oxford and a frequent visitor to “Beaumont”. [17]

Satow’s books and pamphlets were far less in quantity than the Morrison Library, which had been left in Peking and kept on worrying Morrison during his final illness: “My one hope now is to get back to China. I do not wish to die but if I have to die, let it be in Peking among the Chinese who have treated me with such consideration for so many years.” [18]

Hopefully, he would be happy to know that the Morrison Library now forms the nucleus of the Tōyō Bunko [東洋文庫] in Tokyo.

Now, let me conclude with a few words about the Gale digitised collection titled The Papers of Sir Ernest Satow. Sourced from the UK National Archives, the collection consists of Satow’s correspondence and papers (mostly private), letters, diaries, and travel journals covering a period of seven decades (1856–1927). It needs to be noted that the transcription undertaken by me for Satow’s diaries and travel journals has been incorporated into this digital collection, enabling readers to compare the handwritten text with the easily legible transcripts. Browsing through the collection, we can find out more about his life and efforts, which may deserve our best attention. See if Satow’s scribblings are raised with the velvet moss à la Hawthorne, for he once said: “I should like my memory to be vindicated, for I worked hard and have a good conscience about the policy I pursued and recommended to H.M.G.” [19]

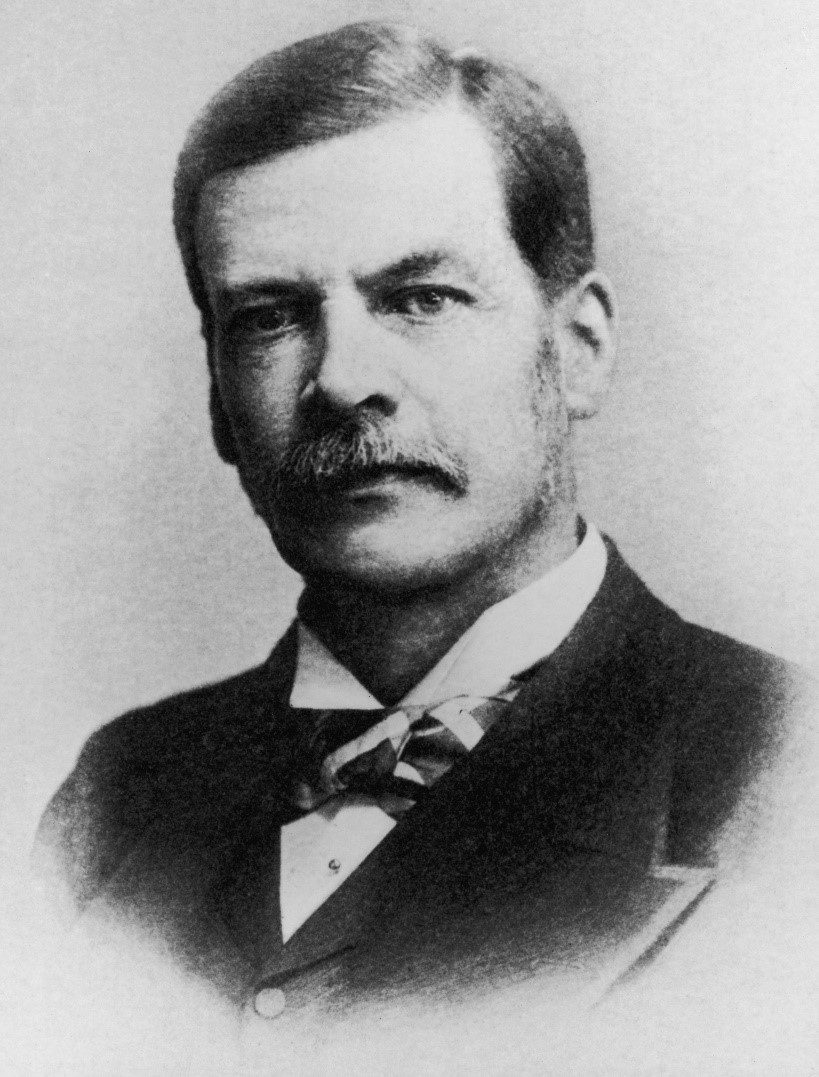

Blog post cover image citation: British diplomat Ernest Mason Satow (1843 – 1929), circa 1890. He served in Japan, China, Siam, Morocco and Uruguay during his career. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images) https://www.gettyimages.com/license/85871734

Notes

[1] Ernest Mason Satow, The Family Chronicle of the English Satows (Oxford: privately printed, 1925), 18.

[2] Laurence Oliphant, Narrative of the Earl of Elgin’s Mission to China and Japan in the years 1857, ’58, ’59, 2 volumes (London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1859).

[3] Ibid., volume II, 1-2.

[4] Laurence Oliphant, Episodes in a Life of Adventure—or Moss from a Rolling Stone (Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1888).

[5] Alexander Michie, The Englishman in China, 2 volumes (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1900).

[6] Richardson’s letter to his father, dated Shanghai 7 December 1855, whose transcription I owe to Mr. Michael Wace, descendant of the Richardson family. “The fact is Aspinal & Co. have smashed for $300,000 & I am in no better position than when I first arrived at Shanghai. However, it does not matter much as I have lots of friends in this part of the world who, I fancy, will give one a leg up if necessary.”

[7] Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Leamington Spa,” Our Old Home (Boston: Houghton Miffin, 1907), 85.

[8] Sir Meyrick Hewlett, Forty Years in China (London: Macmillan & Co., 1943), 35.

[9] George Ernest Morrison (1862–1920) was an adventurer and writer, publishing An Australian in China in 1895 and working as The Times’ first permanent correspondent at Peking during 1897–1912.

[10] Jennie Morrison, letter to Earnest Mason Satow, 22 July 1920, UK National Archives, PRO/30/33/13/9/, 103-106.

[11] George Ernest Morrison diary, 9 & 23 April 1920, Morrison Collection at the Mitchell Library of the State Library, MLMSS 312/26 Item 113 (Sydney, Australia).

[12] Valentine Chirol’s life-long passion was painting in water colours. See Jonathan Cape, With Pen and Brush in Eastern Lands When I was Young (London: Jonathan Cape,1923).

[13] Hugh Trevor-Roper, Hermit of Peking (New York: Penguin Books, 1978).

[14] George Ernest Morrison, letter to John McLeary Brown, 6 May 1920, The Morrison Collection at the Mitchell Library (Sydney, Australia).

[15] “Cherry Blossom Will Be Seen Soon—Finest Trees in Tokyo, in Front of British Embassy—Were Planted by Former British Minister,” Japan Times, 31 March 1915.

[16] Ernest Mason Satow diary, 8 September 1923, UK National Archives, PRO/30/33/17/7/Folio 79 recto. “Yesterday & today I have counted my books, 3387 vols. or there abouts, of which 2008 in my library. Not a room in the house without books. If I were to have all the pamphlets bound there would probably be 3400.”

[17] Johan Huizaga, Erasmus and the Age of Reformation, translated by F. Hopman (New York: Harper Torchbook, 1957), 11. See also Percy Stafford Allen, Editor’s Preface to Erasmus—Lectures and Wayfaring Sketches, edited by Helen Mary Allen (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934).

[18] Cyril Pearl, Morrison of Peking (Sydney: Penguin Books, 1970), 407.

[19] Ernest Mason Satow diary, 29 Nov. 1911, UK National Archives, PRO/30/33/16/12/Folio 34 verso.