By Tom Henderson, Gale Ambassador at Durham University

In December 1929, British newspapers reported on ‘sporadic riots’ taking place in the British colony of Nigeria, targeting Warrant Chiefs and Native Courts across several districts. This was the Ogu Umunwaanyi or ‘Women’s War’: a coordinated insurrection of Igbo women against British colonial rule, ignited by a fear of taxation.

Scholars have focused on this gendering to reveal more complex and systemic causes for the War. Rather than simply the catalysing threat of taxation, the protests came after a long decline in the political power of women in Igbo society. The imposition of a system of Warrant Chiefs had inflated the power of the Igbo men appointed to those roles. Elevated by the status granted them by the colonial regime, chiefs and court workers protected men’s interests, attracting accusations of corruption; some took advantage of their position by stealing from women-dominated markets. This strict hierarchical structure undermined Igbo women’s political institutions, which relied upon communal action and oratory skills before village assemblies, to which Warrant Chiefs were unaccountable.

In extremis, Igbo women had recourse to communal women’s groups. If a group of women felt one of their number had been wronged by a man, the group could unite to ‘sit on’ the individual: gathering at his residence, making a great deal of noise, attacking his hut and intimidating him into submission. This was a traditional way for Igbo women to express grievances that had been ignored. The striking argument of Judith van Allen characterises the ‘Women’s War’ as an amplification of this “sitting” or “making war” on offenders to take on the native administration [1]. The loud, intimidating demonstrations, the destruction of property and the use of ceremonial ‘weapons’ – sticks wrapped in ferns – all support this contention, as does the fact that the women did not kill anybody.

The same cannot be said for the colonial response: 54 people were killed and 57 were wounded by gunfire as the police and even the army were called in to restore order; on one occasion even using a Lewis machine gun against protestors.

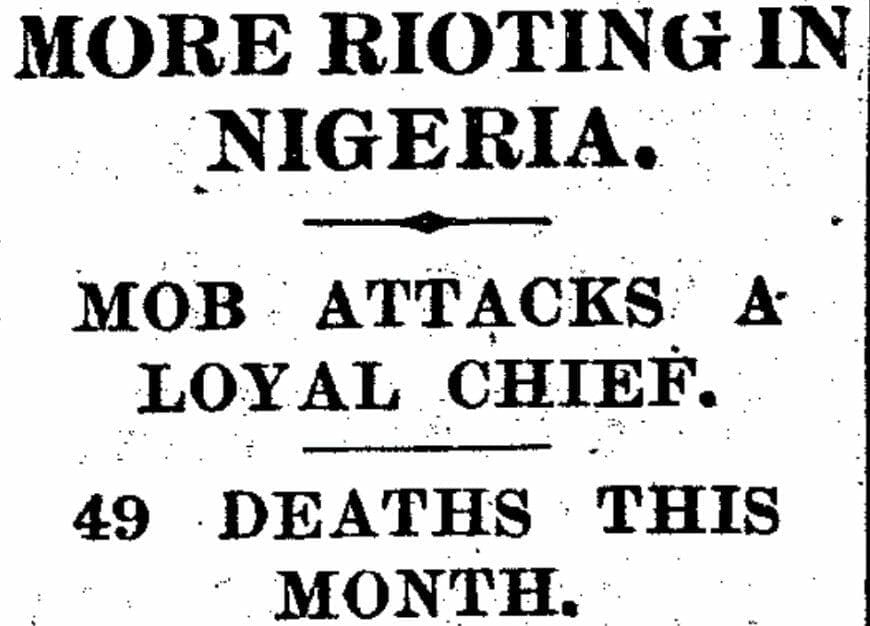

Despite the violence perpetrated against the women, British newspapers were unsympathetic. Initial headlines in The Times focused on the idea that ‘Europeans were assaulted’ over the shooting of protestors [2]; later ones undercut the number of casualties by highlighting that the insurrection was ‘due to a false report’. Claims that disturbances were ‘sporadic’ undermine the collective nature of the rising and its grievances. The fatal acts of colonial forces are softened: they were ‘compelled’ to fire upon the crowds; such action was ‘necessary’. The casualties are cast as the protester’s own fault, and the shooters are presented in passive innocence: The Daily Mail reported that ‘serious rioting’ had ‘result[ed] in 18 women being shot’ as though there hadn’t been anybody actually doing the shooting. The colonial regime is implicitly exonerated of moral responsibility; the women of the uprising are not taken seriously.

This reflects the colonial response. The report of the Aba Commission, issued in mid-1930, demonstrated that the British authorities were completely oblivious to Igbo women’s political institutions. It simultaneously recommended that more attention be paid to ‘the political influence of women’, yet also that ‘it was necessary to forbid mass meetings’. A serious consideration of Igbo political structures would have made these clearly contradictory. As it was, Igbo women’s political power continued to decline. Ironically, the system of ‘native administration’ used by the British was supposed to have as little impact on local politics as possible, but it was completely incompatible with the diffuse and decentralised political setup of Igbo society.

Professor Mary Beard recently asked whether ‘if women are not perceived to be fully within the structures of power, surely it is power that we need to redefine’?[3] The Igbo Women’s War, in its cause and aftermath, is an example of what can happen if no such redefinition occurs.

Blog post cover image citation: “More Rioting in Nigeria.” Daily Mail, 28 Dec. 1929, p. 10. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5osUpX. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

[1] Judith van Allen, ‘“Sitting on a Man”: Colonialism and the Lost Political Institutions of Igbo Women’, Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 6, no. 2 (1972), pp. 165–81.

[2] FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT, ‘Native Unrest In Nigeria’, The Times, 13 December 1929, The Times Digital Archive.

[3] Mary Beard, Women & Power: A Manifesto (London: Profile Books, 2017), p. 67.

Sources and Further Reading:

‘18 Women Shot’. Daily Mail, 19 December 1929. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5u6eH2. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

Allen, Judith van. ‘“Sitting on a Man”: Colonialism and the Lost Political Institutions of Igbo Women’. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 6, no. 2 (1972), pp. 165–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/484197.

Beard, Mary. Women & Power: A Manifesto. London: Profile Books, 2017.

(FROM A NIGERIAN CORRESPONDENT). ‘The Riots In Nigeria’. The Times, 25 August 1930. The Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5u7fo6. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT. ‘Native Unrest In Nigeria’. The Times, 13 December 1929. The Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5u7GG4. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

(FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT). ‘The Nigerian Riots’. The Times, 25 August 1930. The Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5u6wb2. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

‘More Rioting in Nigeria’. Daily Mail, 28 December 1929. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5osUpX. Accessed 6 Feb. 2018.

‘Native Riot in Nigeria’. The Daily Telegraph, 19 December 1929. The Telegraph Historical Archive.