By Seth Cayley, Gale Vice President, Gale Primary Sources. Seth collaborates with our US product teams to direct Gale’s international archive programme.

In January, I had the pleasure of attending the annual British Society for 18th Century Studies (BSECS) Conference. This is one of the liveliest academic conferences that I attend, and always features a diverse array of sessions. Amongst my personal highlights from this year’s conference were a thought-provoking panel on Black Georgians, and a plenary lecture on the culture of letter-writing between women.

However, with my ongoing interest in Digital Humanities, the session that interested me most was delivered by the COMHIS Collective, with the does-what-it-says title of ‘Text and data mining the eighteenth century based on English Short Title Catalogue (ESTC) & Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO)’. (Slides available here). The COMHIS Collective is a research group with members from several Finnish universities, including Mikko Tolonen, Eetu Mäkelä, Leo Lahti and Ville Vaara. (Full disclosure: ECCO is a Gale product, so I had a natural enthusiasm for this project).

At BSECS the group emphasised that text mining can provide insights into use of language and enhance our understanding of conceptual change. Data mining of metadata, on the other hand, can be a useful tool for permitting the quantitative study of material objects. Such data mining has an advantage over text mining in that it can work across languages, allowing for pan-national studies.

The biggest challenge to these types of projects is usually the up-front overhead. As Mikko Tolonen stated, 80% of time spent on a Digital Humanities project is spent cleaning up data, with a further 80% of time then spent on creating algorithms, leaving the project with minus 60% of time for actual exploration and research!

The only way to overcome this is to collaborate. The COMHIS Collective has taken an Open Science approach, with all the steps they have used available on GitHub. If you have access to the data set, you can use their tools to reproduce the results. The tools themselves are available in an R library.

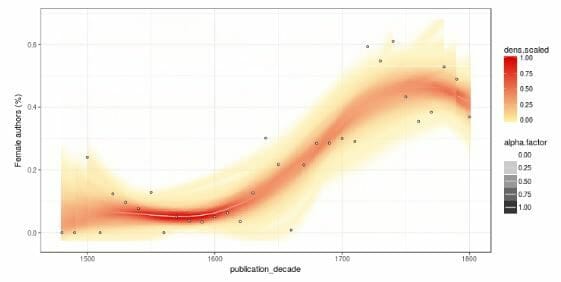

The group argued that metadata has been undervalued as a source for research, but it can be a powerful one. They showed an example of a data visualisation illustrating the proportion of female authors in the ESTC over time. The graph was an s-curve, showing how the proportion went from a low base to a period of sharp increase, until the numbers eventually stabilised and levelled off. Similarly, they have mined data around the physical size of books. At the beginning of the sixteenth century there were only large-format books, but by 1800 book formats were much more diverse.

The collective has developed a series of tools to allow users to mine ECCO, a data set that offers additional opportunities owing to the fact that ECCO contains OCR (Optical Character Recognition) text for each item. One of the tools allows users to visualise the authors who used a particular phrase most frequently. The example of “human nature” was given, for which the most prolific authors included Isaac Watts, David Hume and Henry Fielding. Further analysis allows users to model this by publisher, with J Dodsey being the most prolific publisher of works that discuss human nature in this data set. An audience member pointed out that Dodsey was a well-known Whig. Does this mean that discussions of human nature were an especially Whiggish preoccupation? Maybe.

For me, this last point highlighted the great potential of more widespread adoption of Digital Humanities methodologies. It will not replace traditional scholarship, but will instead allow researchers to find new questions to ask, and ensure that the humanities continue to thrive.

The data set for ECCO (and other Gale archives) is available to libraries that have purchased access to the relevant Gale archive. Please speak to your local Gale representative for more information.