Whilst the media widely documents the racial tensions still present in American society, there tends to be greater coverage of the plight of African Americans, leaving other racial and ethnic minorities under-represented. Given that this Friday, 20th November, is an anniversary of the day a group of Native Americans occupied Alcatraz island to highlight what they claimed to be historical and contemporary exploitation of Indian rights by successive governments, it seems opportune to spend time exploring Gale’s databases and archives to find out what occurred 46 years ago, and what it means for Native Americans today.

Alcatraz was previously a high-security federal prison. By 1969 it had been abandoned, making it politically useful to the protesters, who claimed the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty – which permitted Indians to repossess unused federal property – gave them legal entitlement to the island[1]. They also offered to purchase Alcatraz for $24 in glass beads and red cloth, in bitter reference to what they alleged to be another instance of exploitation; the purchase of Manhattan from Native Americans in 1626[2]. The aims and intentions of the group, calling themselves ‘Indians of All Tribes’, were outlined in a symbolic letter, which is found in the Gale resource US History In Context[3].

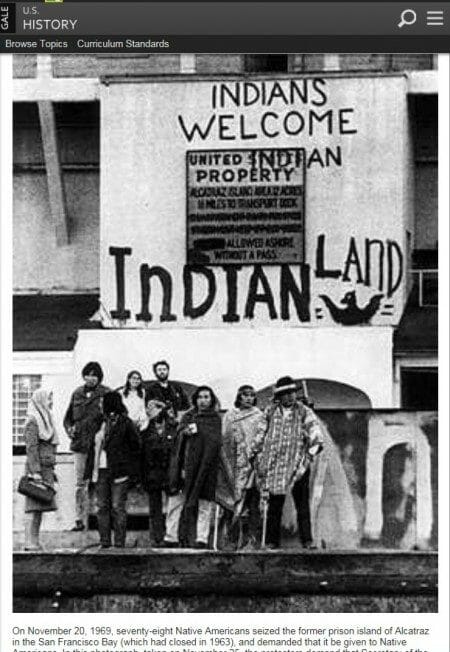

Extracts include; One of the aims of the protesters was to garner the attention of the press, and this was successful; there are numerous iconic images and newspaper reports of the protest, many of which are included in Gale’s resources.

One of the aims of the protesters was to garner the attention of the press, and this was successful; there are numerous iconic images and newspaper reports of the protest, many of which are included in Gale’s resources.

In June 1971 the few Indians left on the island were removed by federal forces, and the protest came to an end without achieving the material or legal gains intended. However, significant press coverage had brought the plight of Indians to the forefront of the political stage, and with heightened recognition came confidence and pride. Thousands made a symbolic visit, but those unable to do so could still draw on the sense of collaboration and empowerment inspired by the occupation, by following the events in the media. A biographical essay on Wilma Mankiller contained in one of Gale’s resources, Academic OneFile, clearly demonstrates these psychological gains by drawing on Mankiller’s own words:

“When Alcatraz occurred, I became aware of what needed to be done to let the rest of the world know that Indians had rights, too. Alcatraz articulated my own feelings about being an Indian[4]”

Likewise, Robert Warrior’s essay in Academic OneFile, ‘The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Indian Self-Determination and The Rise of Indian Activism’, suggests Alcatraz was chronologically important – occurring on the brink of a decade that was to prove explosive for Native American activism; the 1970s[5]. Not only did it inspire direct imitations in the form of other occupations, it can be argued the psychological empowerment engendered by Alcatraz led to the surge of protests in the 1970s such as Wounded Knee and The Longest Walk, and the establishment of educational and cultural programmes nationwide.

Yet the continuous nature of journalism can expose the experiences of individuals long after key events, enabling deeper analysis. The murder of Richard Oakes, a central figure at Alcatraz, by a white man in 1972, and acquittal of his murderer, could be used to argue how little the occupation of Alcatraz achieved for the rights, protection and dignity of Indians.

“Open Season on Indians.” Akwesasne Notes Early Summer, 1973: 37, INDIGENOUS PEOPLES: NORTH AMERICA

Although far from the scale of coverage given to African American protests today, or from the peak of coverage seen in the days of Alcatraz and Wounded Knee, today’s newspapers do carry occasional stories about the current position of Native Americans, and it seems the story is often not optimistic.

In August 2015, the Billings Gazette wrote that the Governor of Montana believes State government is still an ‘obstacle’ to Indian Country economies, highlighting ‘the lack of access to capital and reservation unemployment rates that are often three times the state average’[6]. The same article cites US Senator Steve Daines arguing that tribes are still withheld self-governance. There is even a suggestion from the Vice Chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee that Congress ‘balances the budget on the backs of folks in Indian Country’. This suggests that while personal oppression may have improved with an increase in pride; economic – and sometimes political – oppression continues. Yet in 2012 The Independent (a new addition to the Gale range) ran a powerful article delineating how prevalent the abuse of alcohol remains on many Indian reservations, suggesting 85% of families on the Pine Ridge reservation contain at least one alcoholic, which in turn indicates pride, self-belief and empowerment may also remain low in some Native American communities.

However, newspapers also seem to be increasingly peppered with more positive stories of America’s Native American communities. In 2006 the Times reported on the Seminole tribe bidding $1 billion for the Hard Rock Café chain, and in 2009 it reported a $3 billion pay-out from federal government in compensation for the mismanagement of Indian funds over the past century[8]. Recent coverage also suggests President Obama has engaged in particularly positive interaction with Native American peoples, indicating federal-level support[9].

Consequently, by inspiring further protest, kick-starting grass-roots programmes and fuelling the pride and self-belief necessary to campaign for further rights and attain economic and social success, it is arguable that the Alcatraz occupation had a positive impact on the lives of Native Americans today. Yet it must also be recognised that in some areas the political and economic achievements of Alcatraz were, and remain, limited. Thus, whilst many prosper, the path of Native Americans often remains an uneven and difficult track.

[1] “Alcatraz, Occupation of.” Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Ed. Frederick E. Hoxie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996, ACADEMIC ONEFILE

[2] “Alcatraz, Occupation of.” Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Ed. Frederick E. Hoxie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996, ACADEMIC ONEFILE

[3] Indians of All Tribes “Letter Concerning the Confederation of American Indian Nations” The Native American Experience, Woodbridge, CT: Primary Source Media, 1999. American Journey, U.S. HISTORY IN CONTEXT

[4] “Mankiller, Wilma” Encyclopedia of World Biography, Detroit: Gale, 1998, ACADEMIC ONEFILE

[5] Robert Warrior, “The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Indian Self-Determination and the Rise of Indian Activism.” The Oral History Review 26.1 (1999): 142, ACADEMIC ONEFILE

[6] “Bullock: Government shouldn’t be ‘obstacle’ to Indian Country economy.” Billings Gazette (Billings, MT) 6 Aug. 2015, INFOTRAC NEWSSTAND

[7] “Bullock: Government shouldn’t be ‘obstacle’ to Indian Country economy.” Billings Gazette (Billings, MT) 6 Aug. 2015, INFOTRAC NEWSSTAND

[8] “Fund cowboys pay Indians $3bn” Times (London, England) 9 Dec. 2009: 44. THE TIMES DIGITAL ARCHIVE, 1785-2009

[9] “President Obama Addresses Tribal Nations Conference in Washington.” UPI Photo Collection. 2011, INFOTRAC NEWSSTAND