│By Tom Taborn, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford│

Primary sources can be, let’s face it, intimidating. In the first few weeks of university the idea that we should use them was constantly drummed into me. I, like most other students I know, immediately ignored this advice, and ploughed into the swelling lists of secondary sources. Primary sources seemed like a distraction from the stress of churning out an essay, and the few students who did use them seemed like god-like beings who’d mastered pomodoro timers and bullet journaling in the pram.

Over the course of my first year, however, I realised that they were exactly the opposite. Primary sources are the stressed student’s best friend. Reading what real people thought, how they talked, and what they felt, can make the trickiest topics easier. And more than that, they can be fun. The archives in Gale Primary Sources made using primary sources so much less terrifying as a student for me. This is the story of how my worst essay was saved by a primary source, and how yours can be too.

Tackling an Essay on the Inter-War Period

Last year, if there was one thing I was more scared of than primary sources it was The History of the British Isles 1830-1950. The paper covered 120 years of history in eight weeks, and in each topic, no matter the amount of reading, I felt like I was shooting in the dark. Secondary sources, like David Edgerton’s The Rise and Fall of the British Nation, were fascinating, but they were fighting historical controversies over whole areas of history I’d never touched before.

For me, the worst essay I had was on the Conservative Party in the inter-war period. To answer it, I had to make an argument that explained why the party dominated politics for twenty years. It was a question about electoral calculation, but also about a country that had been rocked by one world war and was heading rapidly into another. Moreover, it was a question that considered a country changing beneath its leaders’ feet as Edwardian society was replaced by revolutions in poetry, economics, and social structure. It was a question where I felt completely out of my depth.

Inter-War Society and the Conservative Party

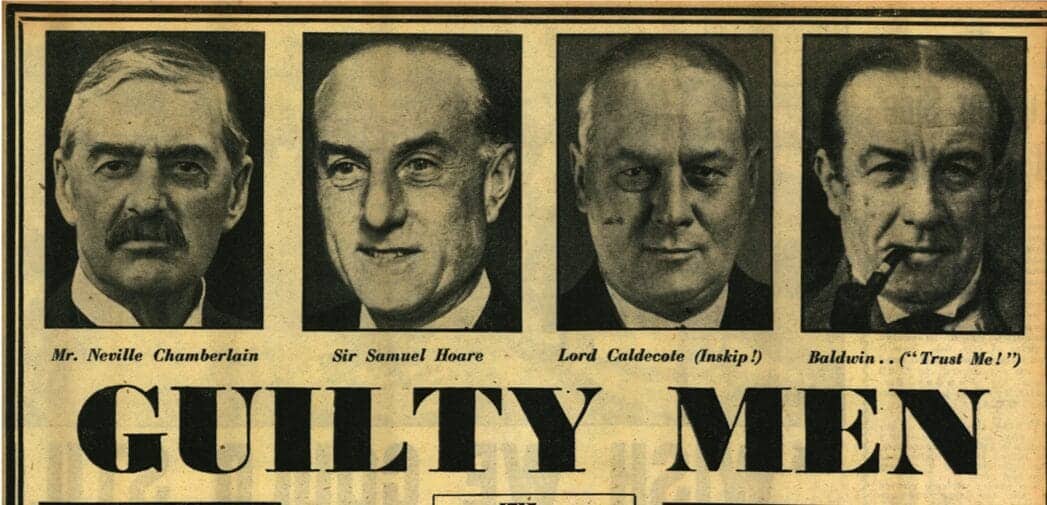

The society of the inter-war years – dramatically confident but also at odds with itself – was one that disappeared as fast as it had arrived in the course of the Second World War. The party that had come to represent that society was Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative Party, which had turned itself into an electoral machine, staying in office for seventeen out of twenty years in the inter-war period. The same party became the ‘Guilty Men’ of 1940 – the party that had betrayed Britain and led what are now seen as twenty years of decay and decline in Britain.

Beyond the questions focused on in the reading – did seat redistribution help facilitate Conservative dominance? What was the impact of new campaigning tactics? How did the new franchise change voting behaviour? – I wanted to know how one party had remained the dominant force in British politics for twenty years, but within the course of three years, had become seen as the cause of Britain’s decline.

Exploring Gale Primary Sources and the Topic Finder

This problem, and the fact that I was getting nowhere with it, was what forced me to take my first look at the archives. The first issue I had with this was that I had no idea which archives I should use. Searching for keywords on my university’s search engine was a dead-end and Google didn’t help me much either, so I looked at my university’s fantastic blog which pointed me to Gale Primary Sources’ archives, and specifically the British Library Newspapers archive, which had more than 6.4 million pages of content.

The problem with so many pages of content is that finding the one document that you need without knowing the tools available can be a nightmare. Luckily, Gale Primary Sources had the useful tool Topic Finder. Typing in ‘Baldwin’ puts the term into a series of easy-to-use bubbles, showing topics and subtopics, and the sources in them. The archive’s Learning Center, just next to the search bar, highlights the other fantastic tools I could have used to look through the archives.

Peace in Our Time

I was fortunate enough to stumble across the document that was really what I needed – an article in the Hull Daily Mail defending Baldwin from 1929. The article didn’t talk about the slogan that we remember, Safety First, but the prayer that Baldwin had invoked a few years earlier in an industrial relations dispute, and which had come to define his premiership. The phrase was ‘peace in our time.’ The biblical reference is remembered because of its use by his successor, Neville Chamberlain, as he celebrated the policy of appeasement. Chamberlain had gently mocked its use by Baldwin in 1928, but it was the phrase that came to define him as a politician.

For me, this was the piece that helped the picture make sense. In my essay, I argued that Baldwin’s electoral success in the inter-war period, and Chamberlain’s complete failure, were inseparable. The use of the line ‘peace in our time’ wasn’t just a coincidence – it was core to the politics of both men. Baldwin had delivered the line in a speech on industrial relations, in which he accepted the principled necessity of a law but argued that it shouldn’t be passed for fear of unrest. This was an approach which was accepted by the British public.

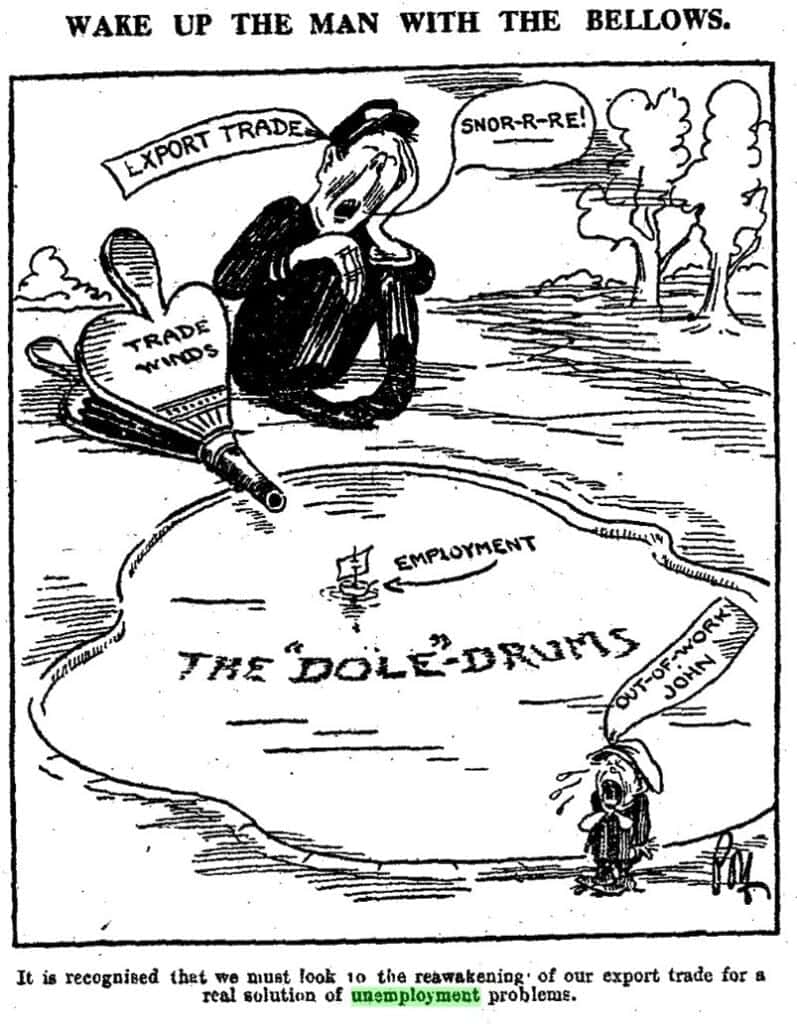

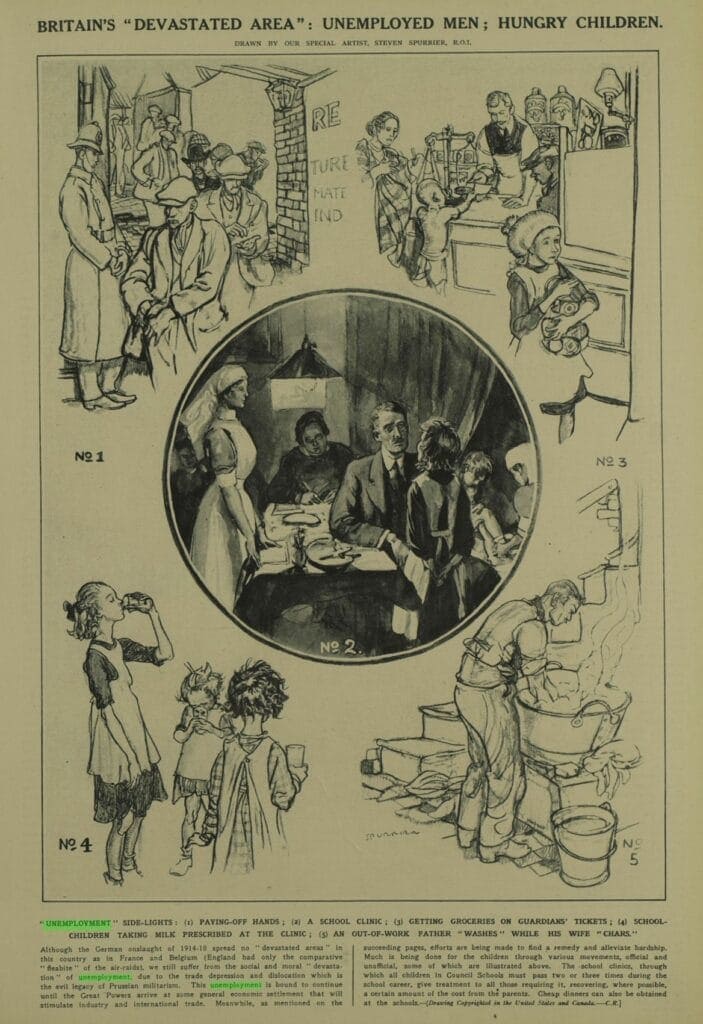

Baldwin didn’t just argue for safety, he argued for peace above dispute, which was central to the consensual politics that allowed the party to dominate those twenty years of politics. It was also an approach which led to the belief that the party had betrayed Britian, not just in Munich, but in its acceptance of mass unemployment between the wars. I argued that the two policies were intimately connected in a specific idea of Conservatism, which was built by the First World War, and which Baldwin and Chamberlain were both signed up to.

The Value of Primary Sources

Primary sources don’t just have to be a last-minute addition or boring chore at the end of the essay. Using archives can help make an essay that seems impossibly complicated human enough to tackle. Gale Primary Sources has some fantastic resources to find the right documents, which you can find on the Learning Center, or in some of the blogs that I’ve linked below.

The most important thing I learned last year, however, was just to get started. It’s not about finding the perfect source; it’s about finding something that gives you a way in.

If you enjoyed reading about how to use primary sources, check out these posts:

- An Undergraduate’s Companion: Finding Primary Sources Using Gale’s Alternative Search Tools

- How Gale Primary Sources Helped Me with My Dissertation – and Can Help You Too!

- How to Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips

Blog post cover image citation: “Guilty Men.” Sunday Mirror, 7 July 1940, p. 7. Mirror Historical Archive, 1903-2000, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HFGAED667575035/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=7bec82c5.