│By Juha Hemanus, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

Many within the university community have faced significant challenges as a result of the pandemic. As a student myself, I’m aware that new difficulties have arisen, be it access to resources or the more isolating study experience. If university is to continue being a productive and stimulating experience for all students it is vital to consider, understand and question how learning practices have changed, what the impacts have been, and what can be done to help students and teachers in the future.

Memories of the 1980s

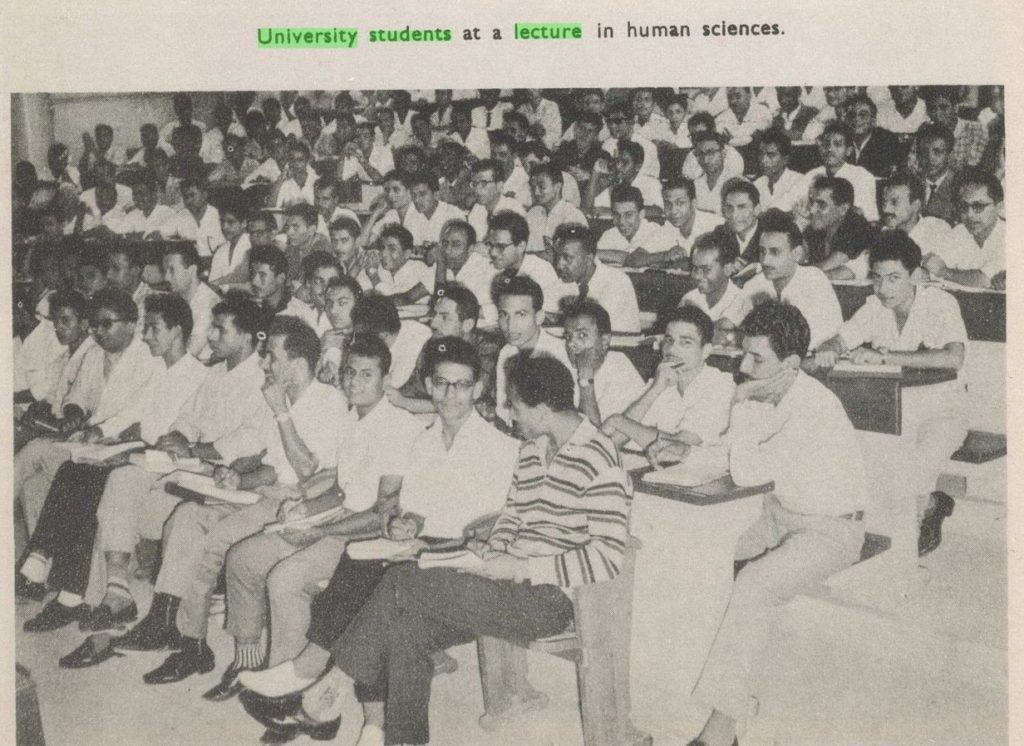

As a mature student, I remember with nostalgia my time at the University of Helsinki in the 1980s. Intense mass lectures were delivered by eminent professors in a lecture hall with no proper air conditioning – but the air was thick with students’ enthusiasm and questions. Not all subjects required lectures, of course. Studying to become a theatre director, as I did, was based on group dynamics and sharing one’s artistic vision with fellow students was vital. These close encounters, with academics and other students, had a powerful effect on students. These learning and teaching practices have been in place in Higher Education for decades and, in some cases (depending on the university), centuries! And many had continued right up until 2020. But when the pandemic hit, things had to change. At many universities, social distancing would be impossible in often tightly packed lecture halls and other indoor spaces. For health reasons, students now need to study in remote ways, but working out how to replicate these powerful interactions and learning experience via digital means can be a real challenge.

Digital resources have been vital during the pandemic

Access to resources, however, is something that has, luckily, not been as much of a challenge as it would have been when I first studied at university in the 1980s. Back then, students started all their academic research making manual searches at university library archives, often with the help of a librarian. Despite the many hardships of the pandemic, we’re actually extremely lucky that we now have the internet and other communications such as video conferencing systems – and that so many primary source archives have been digitised over the last twenty years. If the pandemic had happened when I was first studying at university in the 1980s, we would be in much deeper difficulties preventing the spread of the virus and continuing with studies and research.

Education. N.d. Political Extremism and Radicalism, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DJBRJN410995708/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=58d90ca0&pg=26

Over recent years, it was already the case that digital archives such as Gale Primary Sources have taken a much more significant role in students’ information source collection, but the pandemic has undoubtedly accentuated this effect. As long as we can’t go back to classrooms and libraries physically, digital archives, accessible all the time from everywhere with internet connection, are our salvation. And of course, the many research tools included in digital archives also make the research process much easier.

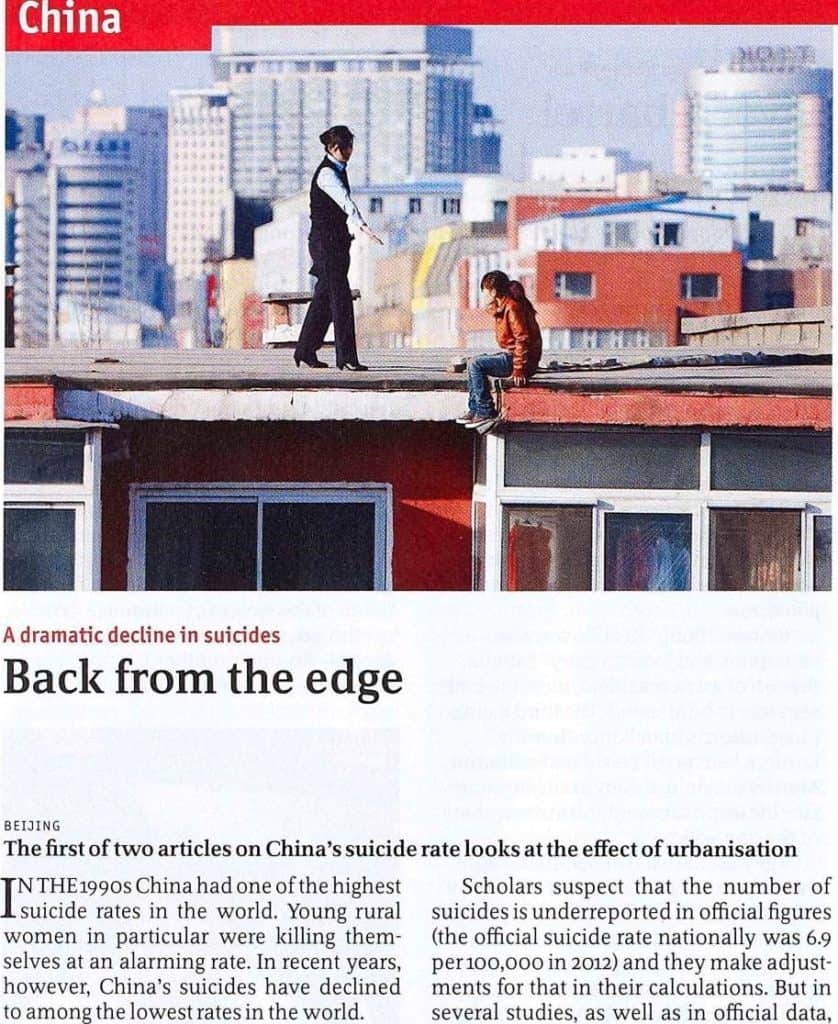

And of course, I’ve found there is immense pleasure to be had in exploring a digital archive – with curiosity to learn more about one’s subject, but also for the accidental and intriguing discoveries you also find! I recently discovered, for example, some fascinating additional information and context that supports studies in Sociology. One of the early masters of this branch of science was Emile Durkheim, a major early scholar on suicide. Digging into Gale Primary Sources I found the article below on modernising China. Refreshing, fun and visual, I found it put in context the scholar’s thoughts and relevance.

Lack of interaction is increasing student anxiety

Despite the ready availability of digital tools and remote resource access, they do not currently meet the need of students to engage with one another and their professors in a way really only possible in-person to receive the reassurance and stimulation so key to the university experience – and many students have been suffering as a result.

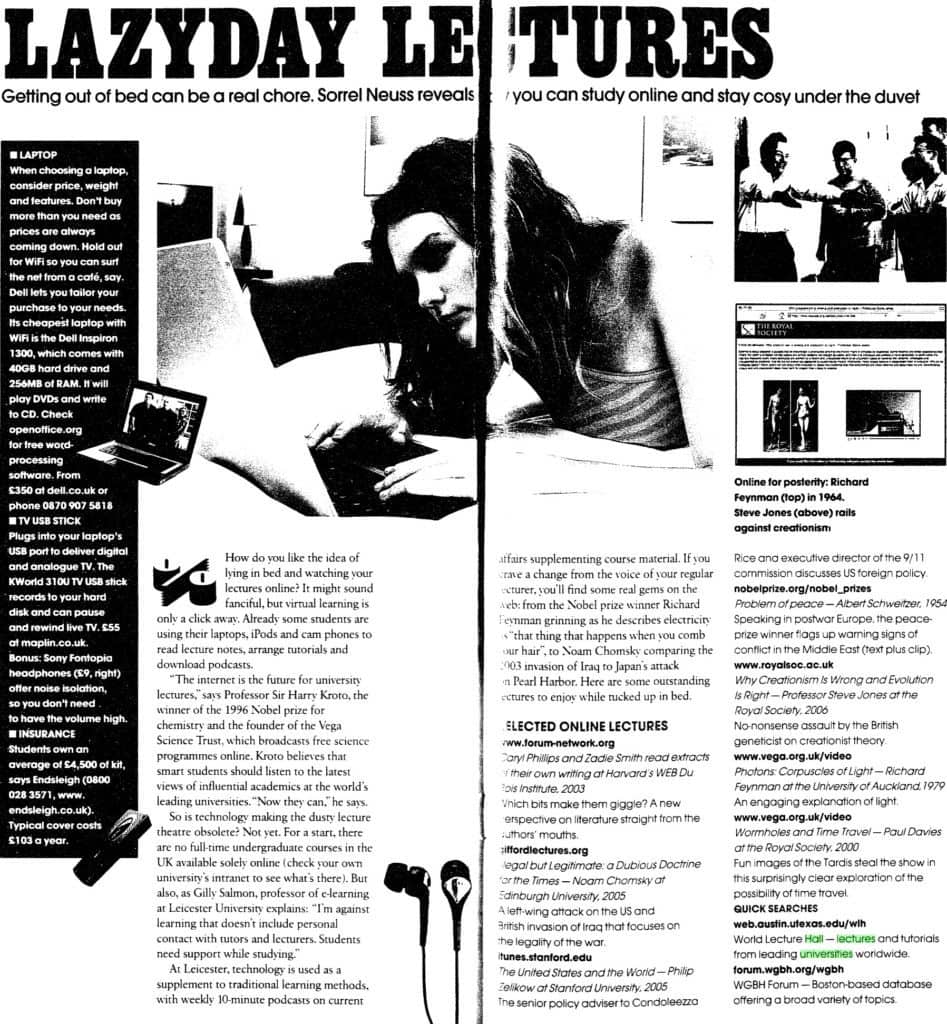

The possibility of digital degrees had been under discussion for years, but the lack of interaction has consistently been used as an argument against an entirely remote course. Whilst as early as 2006, “virtual learning” is described in this Sunday Times article as “only a click away,” the article concludes, it is yet to make “the dusty lecture theatre obsolete”. Indeed, Gilly Salmon, Professor of E-Learning at the University of Leicester, is quoted saying “I’m against learning that doesn’t include personal contact with tutors and lecturers. Students need support whilst studying.”

The reassurance students get (particularly in their first year) at university from studying “en masse” with fellow students, learning together about a subject, is very powerful. Interacting with other first-year students and reading the same introductory materials with two hundred others is somewhat comforting. Since the start of the pandemic, students have been much more isolated, and lacked this early reassurance and introduction to academic practices and interaction.

Education. N.d. Political Extremism and Radicalism,

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DJBRJN410995708/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=58d90ca0

Student and teacher survey at the University of Helsinki

On top of this, there are many other causes of stress and anxiety. For many, the situation has involved new emotional, stress-generating factors, such as feelings of neglect, depression and fear. There have been numerous studies and articles written about the pressure put on our mental health by the pandemic. This survey of 2500 students and several hundred teachers at the University of Helsinki reveals the chronic uncertainty and stress faced by members of the university community, as well as providing other critical insights into the challenges faced by students, teachers and university administration now and in the future. And elsewhere on this blog, my fellow ambassador Evelyn provided an interesting discussion of some of the mental health challenges that students now face, and Emily explained her coping mechanisms, and how she survived studying in lockdown. Studies and articles such as this help us to consider – what needs to be done right now, and how should we adapt to the “new normal” in the long term?

We need to find better ways to support students

What’s clear is that, with the continuing shift to digital interactions – some of which is likely to continue beyond the pandemic – we need to find better ways to support students remotely, ways to re-create the stimulating, motivating “togetherness” achieved via in-person communication, interactions so important to inspiring and enthusing students in their subject and the processes of academia. The type of enthusiasm I remember filling the room during lectures and seminars during my studies in the 1980s.

Is there any chance of systemic help for student anxiety and depression in dealing with missing learning practices in times of a pandemic? How could this be achieved? A fascinating concept I have come across during my research is the idea emotional wisdom of crowds and how to systematise, process and re-distribute it productively back to the community. Perhaps this, or ever-developing technological tools, will provide the answer.

If you enjoyed reading about the university experience before, during and after the pandemic, you might want to check out these blog posts, too:

- Coping at College – Research Resources and Mental Health

- How can pandemic literature help us reflect on the virus and a post-Covid future?

- Why Use Primary Sources?

Blog post cover image citation: Empty lecture theatre. Shared by Pixabay on Pexels.com: https://www.pexels.com/photo/room-chair-lot-356065/