Golf has a long and rich history, with countless books having been written on the origins and development of the game. But if a new history was to be written today with the help of Gale Primary Sources, how much would our knowledge be improved? My suspicion is that it would be improved a good deal, for even a relatively short period of research using Gale Primary Sources unearths thousands of interesting references to golf from the fifteenth century forward, many of which may never have been seen before. Here follows a select sample of the references to golf in the Gale historical collections that could potentially give us a better appreciation of the history of the game and the role it has played in society.

As for the origins of the game, the Star and Evening Advertiser for 3 May 1792, which is to be found in 17th and 18th Century Burney Newspapers Collection, has a column entitled ‘The Antiquity of Golf’.[1] The column reports that the first written evidence of the existence of “the golf” is a statute of 1457 prohibiting the playing of it in order that it not interfere with the practice of archery, which at the time was one of the principal methods of warfare. This is an intriguing piece of legislation. It has been cited before by golf historians but never (as far as I am aware) thought about in any detail. Given that golf courses would have been few and far between in the fifteenth century, it would appear to tell us that archers were choosing to send their arrows flying over the golf links, giving golfers an additional thing to worry about as they stood behind their ball lining up their putt. Either that, or golf was so popular at the time that it was being played and practiced in fields everywhere, leaving the archers nowhere to go. It is a question for a future golf historian to investigate further.

It becomes apparent that ‘golf-obsession’ is no modern-day phenomenon. In State Papers Online, for instance, we find reports of dukes and envoys suddenly abandoning their ambassadorial duties for the day to get to the course and “play at the golf” (for example, Robert Bowes to Lord Burghley, 14 February 1593) [2]. We can also find out what kind of clubs were used in these earlier times. In the 1790 edition of Hoyle’s Games Improved, to be found in Eighteenth Century Collections Online, the chapter on golf says there are six types of clubs, as described in the image below.[3]

How these sixteenth- and seventeenth-century golfers would scoff if they could see the equipment that golfers carry around today, with their allowance of fourteen clubs all of which are custom-made and technologically crafted for the individual user with the aid of ultra-lite acute-dimension 3D golfing software packages and Virtual-Reality simulators – none of which comes with any guarantee of improving your game.

The Gale Primary Sources collections also demonstrate how golf has found its way into every arena of life. Parliamentary discussions on the game, for instance, have been known to descend into the minutia of playing technique and course architecture. An example is from 1905 when the British Parliament, as reported in Punch magazine for 20 December that year, debated the merits of sand bunkers on a golf course and whether they should be left as they lie naturally on the land or be artificially constructed – a debate in which Winston Churchill participated.[4]

Also interesting is how golfing metaphors and analogies have been employed in descriptions of daily routines and other pastimes. On 6 February 1935, Punch ran an article on ‘Face Golf’, in which men are to count their number of strokes with the razor when shaving and try to lower it the next morning.[5] In 1928, Liberty magazine began offering cash prizes for its ‘Word Golf’, whereby you take a word and by the change of one letter, referred to as one ‘stroke’, change it to another, with the object of the game being to build as many words as possible ─ for example, ‘MEAT’ can with one stroke become ‘MOAT’, which with one stroke can become ‘MOST’, and so on.[6]

Looking to a quite different form of human activity, the March-April 1989 edition of the Canadian publication GEM Newsnotes, which is to be found in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality & Gender, has an instructional piece on ‘Indoor Golf’, which is replete with lewd (and hilarious) double entendres. Returning again to Punch, the edition for 15 April 1914 has an illustration of ‘Captive Golf,’ as below.[8]

But maybe the most interesting topic for research is the role that golf has played in the battle of the sexes. The primary source collections are rife with comments of male condescension towards the abilities of female golfers. The article in Punch for 6 May 1876 entitled ‘Disabilities of Woman’ lists one such disability as: “By a masculine assumption unable to play golf”. Even the Times Literary Supplement of 4 June 1914 has a review of a book, ‘Golf for Women,’ written by a man, George Duncan, and going by the review, it is a book that documents everything that is wrong with the female golf swing and woman’s aptitude for the game.[9] The book also includes an inference that women who are overly buxom may as well never bother picking up a club, but if that suggestion is only made by inference in this TLS book review, it is made expressly in the 26 May 1995 edition of the American publication, The Front Page, which is to be found in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender.[10] Yet it can also be gathered from the primary sources that for many years women have in fact played the game; the golf course has not been an exclusively male domain. This is seen in the illustration below, ‘The Golf-Stream’, which appeared in Punch on 10 October 1885.[11] Although the majority of the people in the illustration are men or boys, two at the front are women and both have a club in hand:

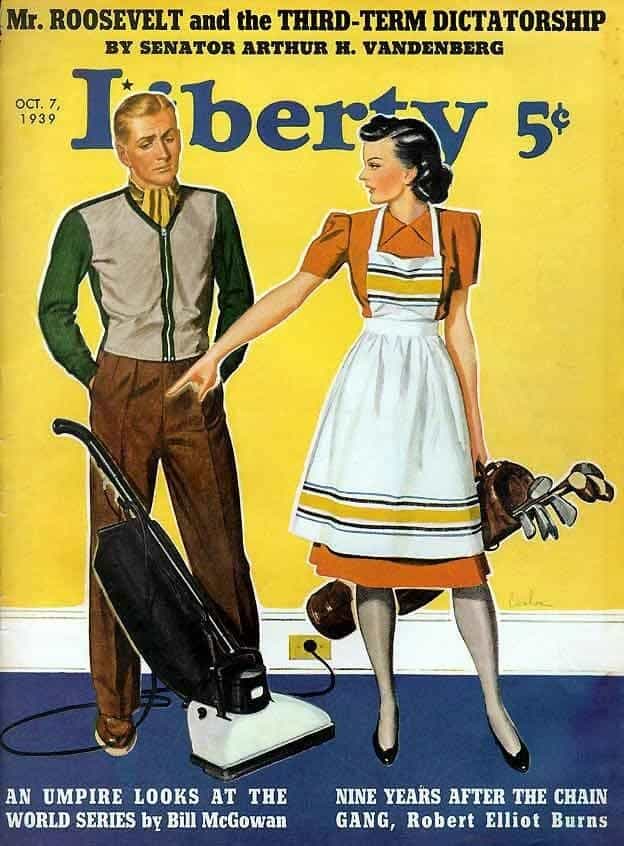

But the final word in this short blog post can go to Liberty magazine. Changing gender roles and the rise of the women’s movement are no better depicted than in this exquisite illustration on the cover of its edition for 7 October 1939:[12]

[1] Star and Evening Advertiser [1788], 3 May 1792. 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56F3d3.

[2] Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, 1509-1603. Ed. M. J. Thorpe. Vol. 2: 1589-1603, Appendix 1543-1592 Edinburgh: H.M. Register House, 1858. State Papers Online, Gale, Cengage Learning, 2017. Crown copyright. URL: http://go.galegroup.com/mss/i.do?id=GALE|MC4307800600&v=2.1&u=webdemo&it=r&p=SPOL&sw=w&viewtype=Calendar For another example: Robert Bowes to Burghley, 14 February 1593: Calendar of State Papers relating to Scotland and Mary, Queen of Scots, 1547-1603. Ed. Annie I. Cameron. Vol. 11: 1593-1595 Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House, 1936. State Papers Online, Gale, Cengage Learning, 2017, Crown copyright. URL: http://go.galegroup.com/mss/i.do?id=GALE|MC4308900054&v=2.1&u=webdemo&it=r&p=SPOL&sw=w&viewtype=Calendar

[3] Hoyle, Edmond. Hoyle’s games improved; being practical treatises on whist, quadrille, piquet, chess, back-gammon, draughts, cricket, Tennis, Quinze, Hazard, Lansquenet, Billiards, and Goff or Golf: In which are contained, the method of betting at those games upon equal or advantageous Terms; including the laws of each, as settled and agreed to, at Brookes’s, White’s, D’Aubigny’s, the Scavoir Vivre, Miles’s, Payne’s, and other Fashionable Houses &c. Revised and corrected by Charles Jones, Esq. A new edition enlarged. Printed for J. F. and C. Rivington, T. Payne and Son, R. Baldwin, B. Law, W. Goldsmith, W. Lowndes, E. Newbery, S. Bladon, G. and T. Wilkiz, and C. Stalker., 1790. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56JaF0.

[4] Golf Illustrated, and Ed. Spectator [A. C. Deane]. “Approach Shots.” Punch, 20 Dec. 1905, p. 433. Punch Historical Archive, 1841-1992, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56Jf70.

[5] “Face Golf.” Punch, 6 Feb. 1935, p. 147. Punch Historical Archive, 1841-1992, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56Jgc1.

[6] “Cash Prizes for Word Golf.” Liberty, 4 Aug. 1928, p. 65. Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56Lgx6.

[7] “Indoor Golf.” GEM Newsnotes, March-April 1989. Archives of Sexuality & Gender, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56LiMX.

[8] Brook, Ricardo. “Captive Golf.” Punch, 15 Apr. 1914, p. 281. Punch Historical Archive, 1841-1992, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56Luz5.

[9] Campbell,, Gerald FitzGerald, and Gerald Campbell,. “Golf for Women.” The Times Literary Supplement, 4 June 1914, p. 272. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56M5K4.

[10] “Golf Analyst Blasts ‘Butch’ Lesbians.” The Front Page, vol. 16, no. 10, 1995, p. 9. Archives of Sexuality & Gender, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56M6b3.

[11] “The Golf-Stream.” Punch, 10 Oct. 1885, p. 174. Punch Historical Archive, 1841-1992, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56M7f9.

[12] “Liberty.” Illustrated by R. J. Cavaliere. Liberty, 7 Oct. 1939. Liberty Magazine Historical Archive, 1924-1950, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/56M9s4.