So writes John Darroch, a British missionary, in the March 1933 issue of The Chinese Recorder, one of the seventeen English-language journals published in or about China that will be included in the upcoming digital collection China from Empire to Republic: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals 1817-1947.

Apparently during the Chinese New Year celebrations, the foreign residents in Shanghai could not avail themselves of their Chinese servants’ help as they would be given leave (or too busy having fun with firecrackers).

On the occasion of Chinese New Year (8 February in 2016), I thought it might be interesting doing a few searches across our databases using that and related terms.

To begin with, I conducted a Term Frequency analysis on the phrase “Chinese New Year” across all 31 databases available on the Gale Artemis: Primary Sources platform.

There is an initial spike in 1841. Curious, I click on the dot in the graph to display the documents in Gale Artemis: Primary Sources from that year.

Apparently, 1841 was in the midst of the First Opium War, and “Chinese New Year” was mentioned in one of the terms of the Convention of Chuenpee, which also stated the cession of Hong Kong to the British for the first time (though not officially ratified by until the Treaty of Nanking the following year). Err… not very auspicious. Especially not for the Chinese.

Undaunted, I try the next peak, 1897.

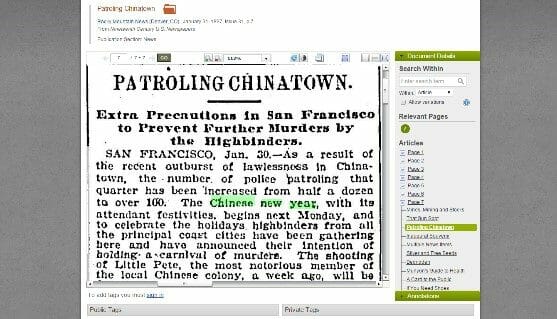

This time the bulk of hits come from American newspapers (mainly from Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers), and they seem to be reporting on Chinatown in San Francisco, but wait – “highbinders”? “carnival of murders”?? … Apparently “Little Pete”, a prominent Chinatown gangster, was murdered right before the new year and the police were on full alert for fear of a war of retribution…

Now there must be something happier – how about 2004, the last and highest peak observed in this graph?

Celebrations in Trafalgar Square, 20 Top Dim Sum …now that’s more like it!

The “Monkey business” headline from The Independent Digital Archive reminds me that in 2004, like 2016, the Chinese New Year is a Monkey Year in the Chinese zodiac. So perhaps a “monkey” search in our databases is in order.

Again, I turn to the upcoming China from Empire to Republic material and find this entry, this time from another periodical, The China Review:

The “Wu” referred to here is none other than Sun Wu Kong, or the Monkey King, who is the beloved protagonist of the Chinese classical novel Journey to the West. The article quoted here summarizes the plot and describes some of its highlights, such as this use of his magical hairs, each of which can transform itself into a monkey. Every Chinese child knows the story of Sun Wu Kong, from his birth from a giant stone, his wrecking havoc in the Heavenly Kingdom, his imprisonment by Buddha, and his subsequent release to accompany the monk Xuanzang on an adventurous trip to the West to retrieve the Buddhist sutras.

And here I conclude my “monkeying around” with our historical databases – Happy Chinese New Year!!

For more information about China from Empire to Republic: Missionary, Sinology, and Literary Periodicals 1817-1947 and Gale Artemis: Primary Sources or to request a trial, please get in touch with us today.