│By Torsti Grönberg, Gale Ambassador at the University of Helsinki│

Historian Jo Tollebeek once wrote that increasing “scientification” of history at the end of the nineteenth century produced a new kind of archival-fantasy: a belief that all relevant documents from the past could be gathered. Nowadays it is vital to comprehend and take into account the diversity of an archive. Every archive is bound not only to its history and context but also the demands of the current era. At the end of the day, an archive is in of itself an intellectual problem and a cultural artefact to be studied. Historian Natalie Zemon Davis has also made the important point that, even though the world of archives has encountered many changes, the most important aspect is still the same: when you read documents in an archive you have a physical link to the past in front of you that connects you to people long dead and strengthens the researchers attempt to tell about the past as honestly as possible.1

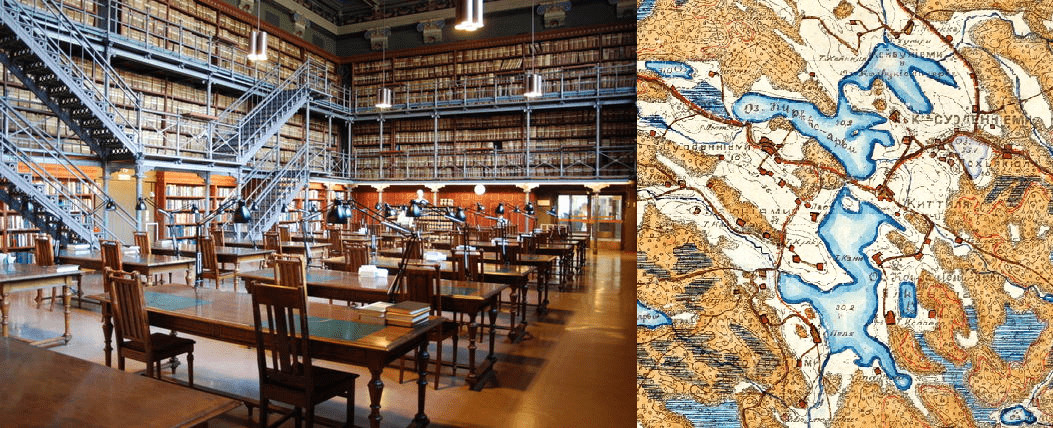

The Finnish National Archives

The section above is a translated and paraphrased version of parts of the introduction to a 2021 book called Arkistot ja kulttuuriperintö (Archives and Cultural Heritage) written by Hupaniittu and Peltonen, published by the Finnish Literature Society, which I think is a good demonstration of the importance of archives to Finnish cultural heritage.2 Archives matter, and the crown jewel of Finnish archives are the National Archives of Finland. It is the duty of the National Archives to ensure that records and documents belonging to the national cultural heritage are preserved for future generations.

From 1880 onwards, the directors of the National Archives held the title of State Archivist. Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karl_August_Bomansson.JPG

The Finnish National Archives are massive. They hold around 210 shelf-kilometres of records dating from the Middle Ages to the present day. The oldest document, a letter of protection given by King Birger to the women of Karelia, dates from 1316. The oldest continuous series of records, which are the accounts of the voudintilit (bailiffs), begin at the end of the 1530s. The archives also hold series of accounts of the provincial administration, court records and land survey maps dating from the period when Finland was a part of the kingdom of Sweden. The most important sources from the period of autonomy are the large archives of the Senate, the State Secretariat and the Chancery of the Governor-General.

My Interest in Finnish History and the Cold War

Archives make it possible to interrogate the past and the past can also be a mirror which we use to analyse the present. If we are really clever, we can follow the steps that have led to the present moment and find some insight or greater understanding. Current events in Europe have rekindled my interests in Cold War history, since all pillars of Finnish foreign policy have collapsed this year and Finland must once more deal with a perilous security situation on its eastern border.

This interest has a very personal nature since I have done a year of military service in the Finnish Defence Forces and, if the worst came to be and Russia attempted to realise their expansionist ambitions, I would be heading to the front with my brothers and sisters in arms. It is a strange feeling. I have increased the amount of running in my weekly exercise to make sure I will be in marching shape if the call comes and we have to mobilise, and also found myself perusing through Gale Primary Sources to read documents about Finnish history from the Cold War period.

US-Finnish relations during the Cold War

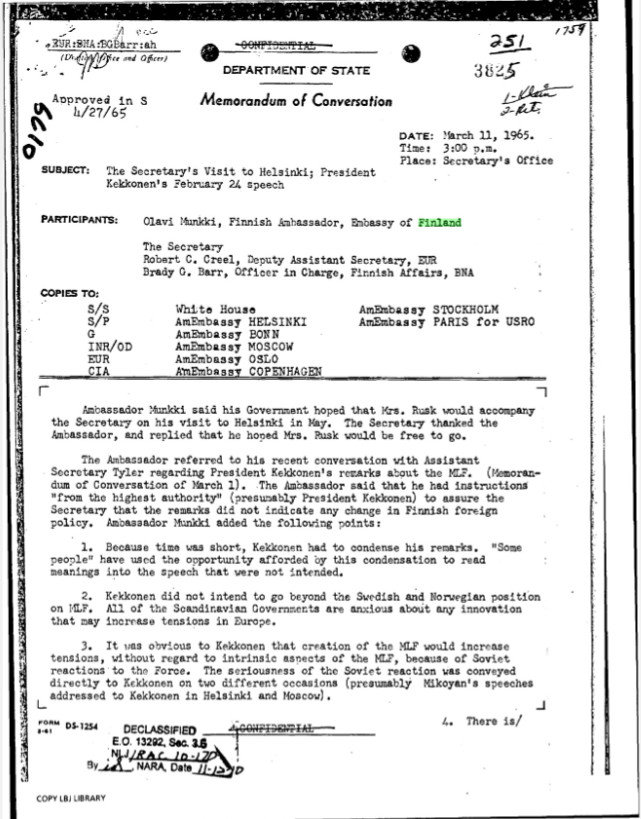

Gale Primary Sources is a very interesting and rich resource for the study of Finnish history. The U.S. Declassified Documents Online archive is an especially interesting resource for those who want a deeper look into US-Finnish relations. One of the sources I found in the archive that I found most interesting is a summary of a meeting in Helsinki between Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Finnish Ambassador Olavi Munkki, and other U.S. and Finnish government officials: “The discussion centered on an American proposal to produce a Multilateral Force (MLF) within NATO, equipped with a fleet of submarines and warships, each manned by international NATO crews, and armed with multiple nuclear-armed Polaris ballistic missiles”.

In this conversation, the Finnish ambassador Olavi Munkki clarifies some parts of President Kekkonen’s earlier speech to US officials and stresses that Finnish foreign policy has not changed. According to Munkki, Kekkonen did not intend to go beyond the Swedish and Norwegian position on MLF. All of the Scandinavian governments are anxious about any innovation that may increase tensions in Europe.

Summary of a Helsinki meeting between Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Finnish President Urho Kekkonen, and other U.S. and Finnish government officials. Department of State, Mar. 11, 1965. U.S. Declassified Documents Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CK2349578587/USDD?u=uhelsink&sid=bookmark-USDD&xid=f9cc66b4&pg=1

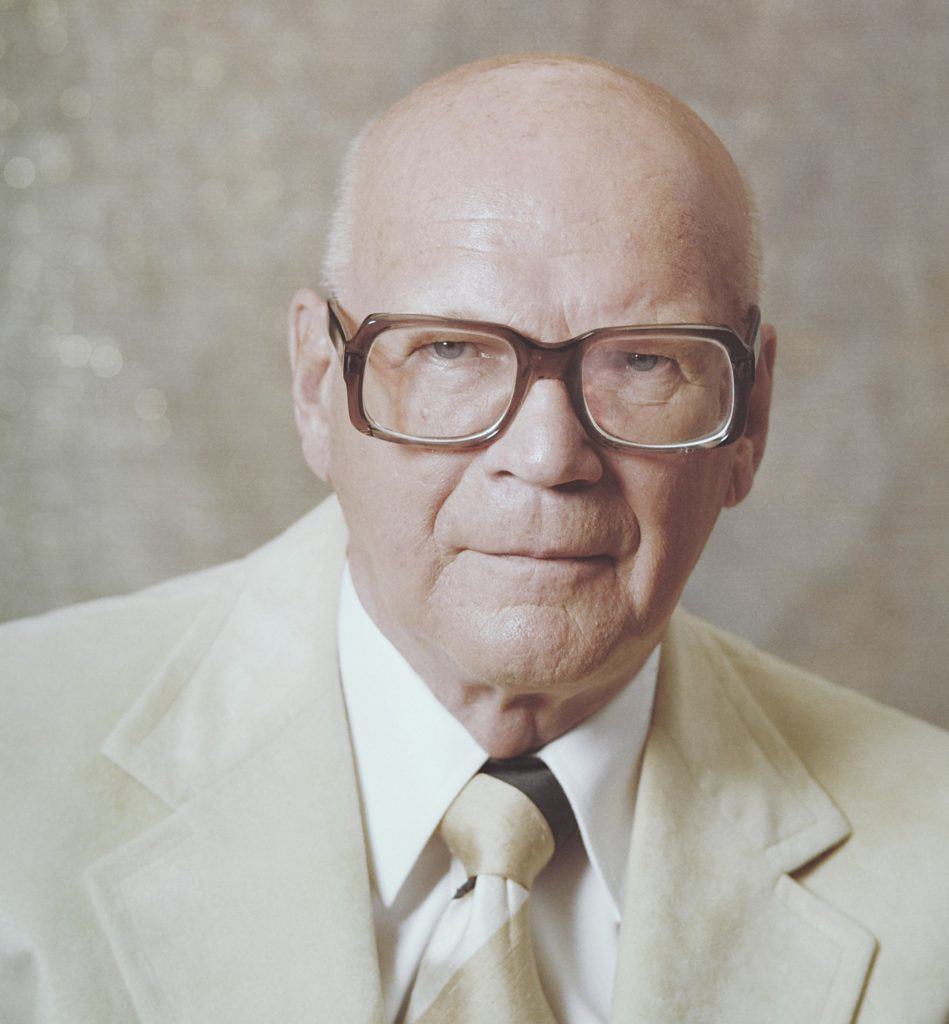

Finnish Heritage Agency, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Urho-Kekkonen-1977-c.jpg

Increasing tensions between NATO and the Soviet Union

It was obvious to Kekkonen that creation of the MLF would increase tensions in Europe and between NATO and the Soviet Union, because of Soviet reactions to the new Force. The seriousness of the Soviet reaction was conveyed directly to Kekkonen on two separate occasions (presumably Mikoyan’s speeches addressed to Kekkonen in Helsinki and Moscow).

This document provides a very interesting inside look into the conversations US and Finnish officials were having during the Cold War, especially when you consider the very strong tradition of Finnish neutrality and third-party position between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. In this memorandum, the Finnish ambassador Olavi Munkki clearly states that “if the question of proliferation or German control is a genuine Soviet fear, we can help to prove that the fear is groundless as soon as the plans for the MLF are complete. If, on the other hand, the real Soviet objection is based on their dislike of any measure that binds the NATO powers closer together, we can be of no help to them.”

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Olavi_Munkki.jpg

Munkki also makes the point that like other NATO measures, the MLF has been the subject of open discussion. According to him “this is not true of military measures taken within the Warsaw Pact. We know that Soviet missiles are stationed within the Warsaw Pact countries. Granting the logical assumption that these missiles are equipped with nuclear warheads, it is obvious that the Soviet Union may have created its own version of the MLF without open discussion or dissent. We see no reason, therefore, why we should feel defensive about the question of the Multilateral Nuclear Force”.

A physical link to the past

Even though the multilateral force was an American proposal that was never adopted, it is fascinating to read about the talks between US and Finnish officials, especially when it is clear that even though the proposal made the Finnish government anxious, they were still willing to offer help in mediating between NATO and the Soviet Union. The Finnish foreign policy during the Cold War was based on a tricky balancing act between two great powers and the U.S. Declassified Documents Online archive provides a magnificent connection to the people and the events that shaped US-Finnish relations for decades, and provides great context to the current political situation.

If you enjoyed this exploration of Finnish history, you might like:

- A Peep into Finnish War History with Gale Primary Sources

- Suomi mainittu! – Finland in American News in the Late Nineteenth Century

- 100 years since Finland declared independence: a look back at the creation of a nation

If you’re interested in international relations, diplomacy, government documents and the Cold War, try:

- Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth Century British Intelligence, Monitoring the World

- Soviet agricultural experiments, hibernation, the bomb, and other curious facts behind Science Fiction stories

- A Global Security Crisis: A Future Under Threat

If you enjoyed reading about how archives contribute to the preservation of national history and heritage, you might like:

- History Lecturer uses Gale Primary Sources to Research Spanish National Pride

- Nazi Germany, Ancient Rome: The appropriation of classical culture for the formulation of national identity

- Liverpool: A city overshadowed by the Beatles?

Blog post cover image citation: Photo from inside the National Archives of Finland (available through Wikimedia Commons) combined with extract from the Senate map collection at the National Archives of Finland (available through Wikimedia Commons). Both images are in the public domain.

- Hupaniittu, O., & Peltonen, U.-M. (2021). Arkistot ja kulttuuriperintö. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21435/tl.268

- Hupaniittu, O., & Peltonen, U.-M. (2021). Arkistot ja kulttuuriperintö. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21435/tl.268