│By Rebecca Bowden, Associate Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

During the 1960s and 1970s, the second wave feminist movement took off. Catalysed in the United States by Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), it quickly spread to other Western countries, focusing on issues of equality and discrimination, including rape, reproductive rights, domestic violence and workplace harassment. Central to this fight were feminist periodicals – an opportunity for women to communicate their narratives in their own voices, free of the influence of men. Many of these periodicals are now preserved in archives.

Putting Feminism on the Newsstands

While “mainstream” women’s magazines of the time focused increasingly on commercialism, viewing female readers as consumers, feminist publications, including periodicals and newsletters, offered an alternative; an opportunity for women to control and find the coverage that they wanted. One of the most well known of these was the UK’s Spare Rib, a feminist magazine that challenged stereotypes and supported collective solutions. According to Martin Conboy in his book Journalism in Britain, A Historical Introduction (2011), Spare Rib “aimed to put feminism on the newsstands by adopting a broad political agenda to target a mass readership of both feminists and those ripe for persuasion.”1

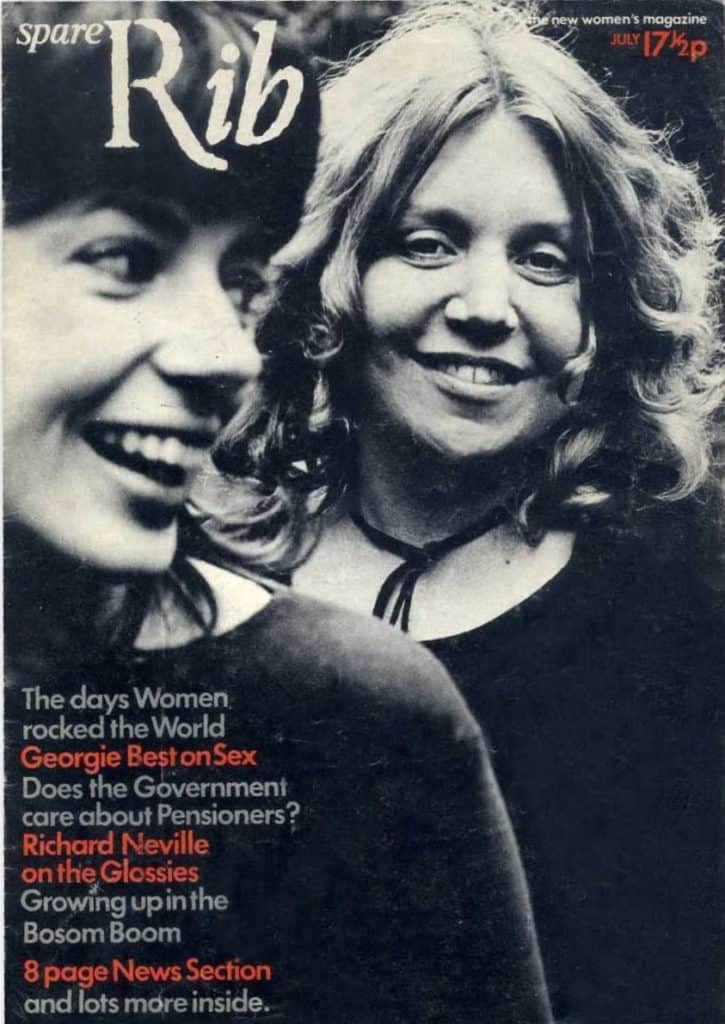

An American Liberal Feminist Magazine

Ms. Magazine could easily be called the US equivalent to Spare Rib; the liberal feminist magazine was founded by Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes in 1971 to address topics that women cared about, as opposed to simply the domestic topics covered by the mainstream press. Quickly gaining national success, and with key contributors including Angela Davis, Alice Walker, Susan Faludi and Barbara Ehrenreich, Ms. was a landmark institution in both women’s rights and American journalism.

Smaller feminist magazines

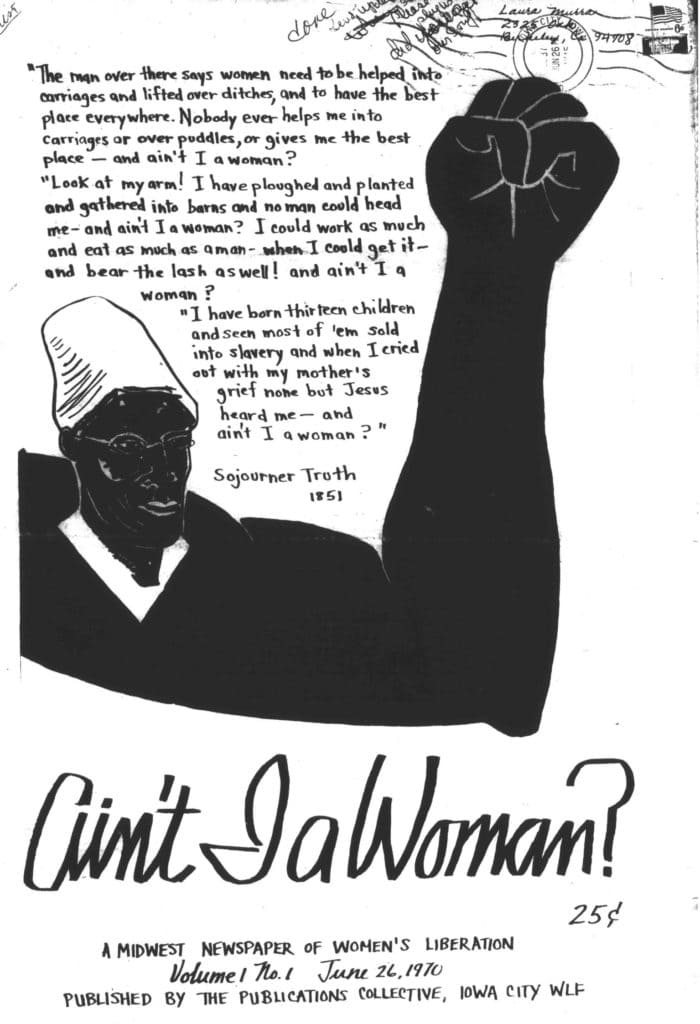

During this period many smaller-scale feminist periodicals also came into being, in response to the same issue: that there was little for women to read that was actually controlled by women and focused on the very real issues that were central to female existence. One example found in Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive: Issues and Identities is the newsletter Ain’t I a Woman? published in Iowa City during the 1970s. In the editorial note of the first issue, the writers explain that they were prompted to start the publication because the University Paper and commercial town paper then available to them were lacking. “Neither” they explain, “can be trusted to function as a service for the people who read them…They are controlled by capitalist interests and concerns. Both, as most newspapers, display unmitigated sexism.” It was out of this discontent that many of the underground papers that fuelled the second-wave feminist movement were born – both well-known examples such as Ms. and Spare Rib, and their lesser-known counterparts.

Significantly, Ain’t I a Woman? and the Iowa City Women’s Press that published it are key examples of the strong feminist networks that formed outside of the traditional urban centres which are usually the focus of discussion about the Women’s Liberation Movement. As in other areas, Iowa City’s feminism emerged from the politicised university community, and formed a hub for feminist communication activities in the Midwest. You can read a lot more about Ain’t I a Woman? in Karan Harker’s post “Power to all the people or to none”: Grassroots activism in amateur publications written by women, African Americans and the LGBT+ community.

Periodicals were “vital to sustaining feminism as a movement”

According to Beins and Enzer’s article in Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies (2013), while periodicals and newsletters such as Ain’t I a Woman “offer insight into the politics, practices and ideals of feminists in a particular place, print cultures also reveal the dynamic and wide ranging networks that were vital to sustaining feminism as a movement and political identity.”2 And like Ain’t I a Woman, many feminist periodicals published at the local level, with the intention of building communication networks amongst women in order to further the cause, though many also had aspirations to grow further.

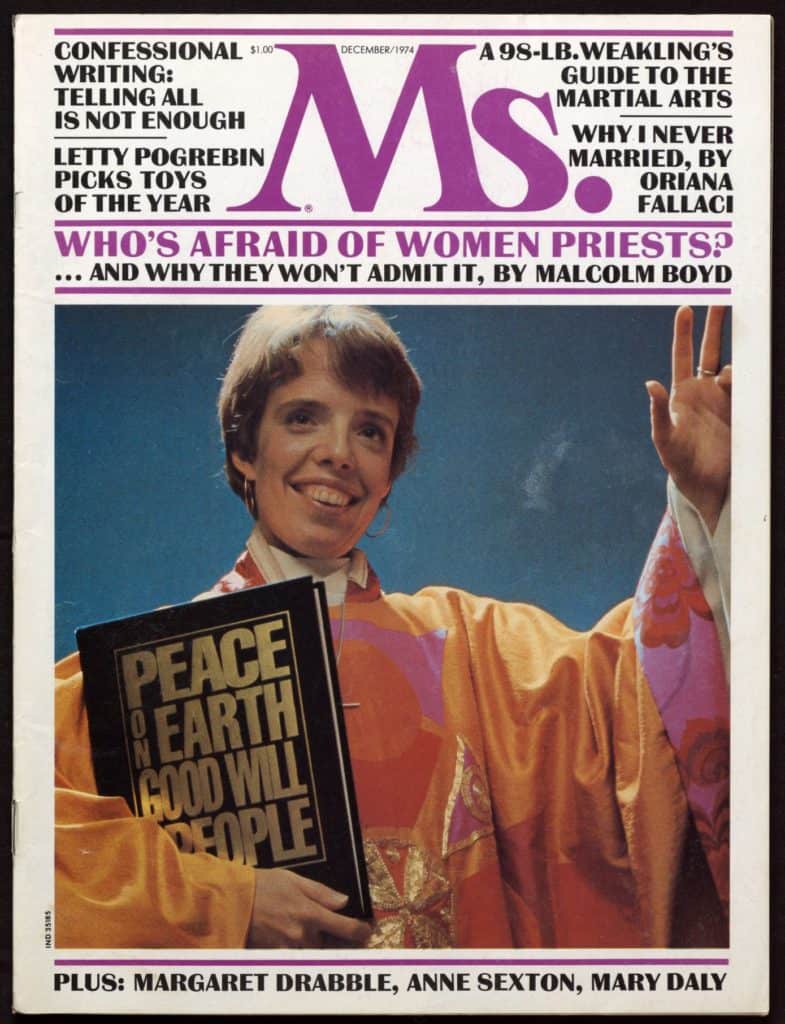

This is seen through issues of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s The Amazon, copies of which can also be found in Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive: Issues and Identities. In the first issue the writers explain that the periodical is “the first attempt at meeting the needs of women to communicate with each other city-wide,” going on to say that “the hope is that eventually the paper will move off the campus and become representative of the Milwaukee women’s movement”. In issue two their circulation had already increased to a couple of thousand copies, and the editors show their aims, that “hopefully, newsprint is next and from there, who knows, we may become a daily”. Even with their big ambition, the content of these short papers remains focused on the local, promoting courses offered by the university, requesting a women’s centre on campus and highlighting local news and events. Local periodicals were a way for feminists to build their communities and to connect with like-minded women.

The Importance of Personal Experience

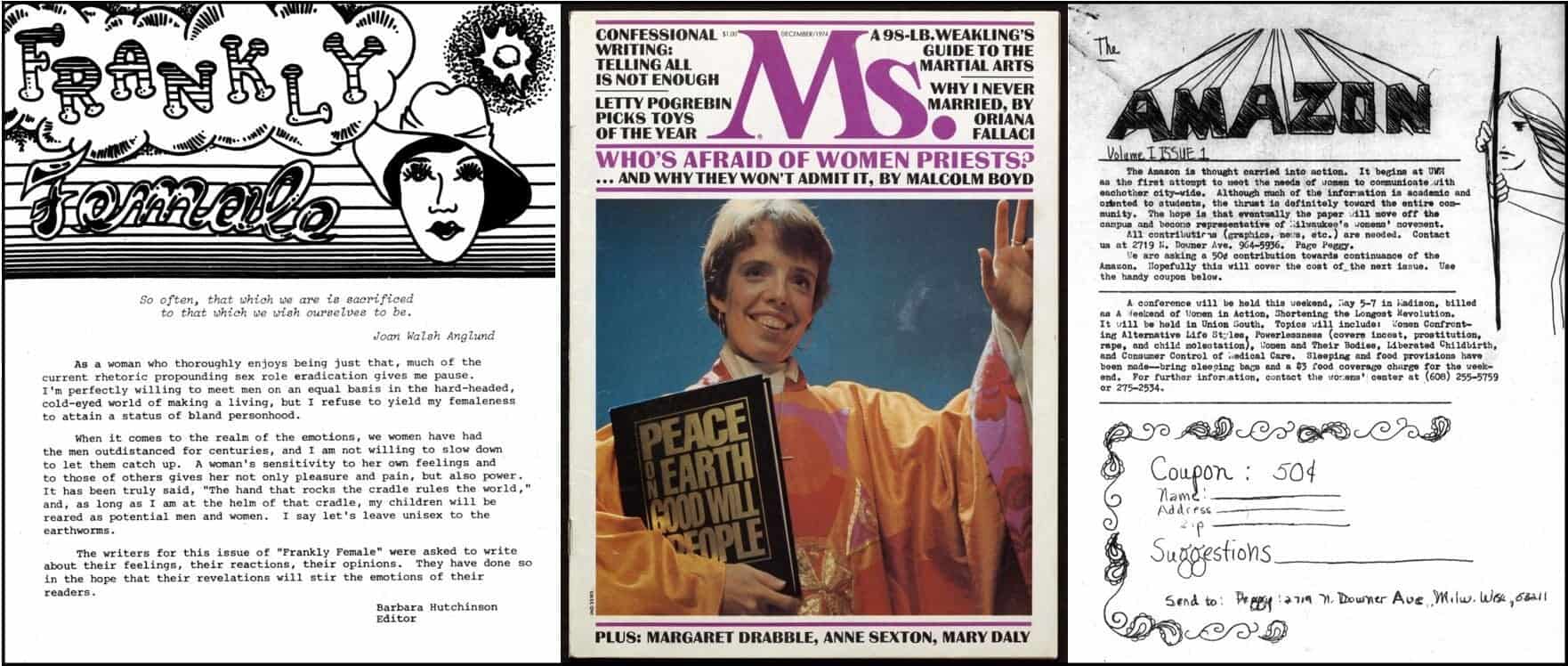

The idea of periodicals being used to build feminist communities is furthered in the use of personal experience. According to Agatha Beins in her book Liberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement Identity (2017), by printing stories about women’s personal experience, periodicals brought activism into the personal sphere, creating space for feminism by inviting readers into what would otherwise be private, unspoken moments.3 In the periodical Frankly Female, for example, the editor explains how all of the writers were asked to write about their feelings, their reactions and their opinions, because “a woman’s sensitivity to her own feelings and to those of others gives her not only pleasure and pain, but also power”. The issue explores a number of topics, including love, abortion, work, housewifery and grief from a personal perspective, weaving feminism throughout.

Published at both the local and national level, feminist periodicals and newsletters were a central part of the Women’s Liberation Movement, giving women a vehicle through which to explore their experiences and build communities free of the constraints of mainstream media and the male-dominated sphere. By exploring the archives and uncovering these fascinating publications, we can learn about the issues that were important to second-wave feminists, and the mediums through which they were able to make their voices heard.

If you enjoyed reading about the feminist periodicals available in Gale’s archives, you might like to read:

- “Power to all the people or to none”: Grassroots activism in amateur publications written by women, African Americans and the LGBT+ community

- Birth Control: A History in Women’s Voices

- “When is a Woman…?” Exploring Cultural Expectations of Women Advocated in Historical Newspapers

- Leading Ladies: The actresses who fought for women’s suffrage

- Martin Conboy, Journalism in Britain, A Historical Introduction, (London: Sage Publications Ltd), 2011.

- Agatha Beins and Julia Enszer, ‘”We Couldn’t Get Them Printed,” So We Learned to Print: Ain’t I a Woman? and the Iowa City Women’s Press’ in Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol.34, No.2 (2013), pp.186-221.

- Agatha Beins, Liberation in Print: Feminist Periodicals and Social Movement Identity, (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press), 2017.